In the US and elsewhere, acceptance of public health measures, including vaccines often falls along partisan lines, with Republicans being more hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine compared to Democrats. In new research Ian G. Anson and John V. Kane test whether partisanship can be used to encourage vaccine take-up. They find that framing getting the COVID-19 vaccine as a way to ensure people can vote – or a “shot to win” – makes Republicans more likely to get vaccinated.

In the US and elsewhere, acceptance of public health measures, including vaccines often falls along partisan lines, with Republicans being more hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine compared to Democrats. In new research Ian G. Anson and John V. Kane test whether partisanship can be used to encourage vaccine take-up. They find that framing getting the COVID-19 vaccine as a way to ensure people can vote – or a “shot to win” – makes Republicans more likely to get vaccinated.

It’s no secret that in the contemporary United States, Republicans and Democrats are bitter enemies. One of the biggest trends in modern American politics is partisans’ (those who support one political party over another) growing belief that their opponents are morally repugnant and hopelessly incompetent. Partisans, fueled in part by this antagonistic political climate, often refuse to listen to anyone but their trusted partisan allies. Taken together, these trends can create big problems for society.

One such problem is the issue of hesitancy to take vaccines. Spurred in part by the loud debate in rightwing media over COVID-19 vaccination, Republicans are now lagging Democrats and politically unaffiliated Americans in a variety of vaccination rates. At present, childhood vaccines and seasonal flu vaccines are increasingly being viewed with skepticism among Republicans, despite decades of scientific evidence of their efficacy and importance. Indeed, recent research finds “spillover effects” from hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine to other vaccines. These trends have major consequences for public health—as evidenced by the recent resurgence of measles in the United States.

If partisanship is contributing to public problems in the United States, we propose a novel solution, especially when other strategies no longer seem to be working: leveraging partisans’ own bias in favor of their party to encourage them to do what is socially responsible. This is precisely what we investigate in our new research.

Leveraging partisanship to encourage vaccination.

In 2021, with COVID-19 posing an ongoing critical public health threat, we conducted an online survey experiment on partisans’ attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine. To measure the effects of different messaging on partisans’ openness towards COVID-19 vaccination, we randomly divided the roughly 1,200 survey respondents into three experimental groups.

Other studies have sought to understand how partisan messaging can encourage vaccination, but we took a different approach. We sought to understand whether the threat of electoral loss could be especially persuasive to partisans who are intensely antagonistic towards the other party. Because of such strong partisan bias, we reasoned that respondents would really not like the idea of losing an election to the other party. Indeed, earlier studies show evidence that electoral loss causes partisans to feel a great deal of negative emotions.

But would this pattern be enough to overcome Republicans’ already-strong resistance to vaccination? (At the time we fielded our study, Republicans were roughly 20 percent less likely to have received one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine than Democrats.)

To test this possibility, we created a “shot to win” (STW) message designed to remind partisans of the threat of electoral loss. To ensure this messaging would be effective, we sought to remind partisans that becoming too unhealthy to vote could hurt their party’s electoral chances. Thus, we sought to encourage vaccination not by arguing that it is the best course of action for public health and safety, but by arguing that failing to do so would endanger their party’s hopes of winning upcoming elections. As it turned out, this argument wasn’t merely hypothetical: later studies would show a strong link between partisan vote share and excess death rates across US counties.

We also sought to ensure that any effect of the STW messaging was not due to the mere receipt of a pro-vaccine message from a partisan ally. Our third experimental group therefore received a generic message from trusted partisan elites—an elite cue (EC)—without the added layer of a “shot to win” argument. By comparing this group to our control group and the STW group, we would be able to make stronger claims about the efficacy of our novel messaging.

“Defeat the Mandates DC (2022 Jan)” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Anthony Crider

In the study, we measured vaccine openness using a variety of measures. In addition to an expressed willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, we also asked about respondents’ willingness to help friends and family members get vaccinated, whether they would seek out more information about vaccines as well as the location of vaccination clinics, and their willingness to receive a booster shot.

Get the shot if you want to win: A uniquely persuasive argument.

In our study, we primarily sought to understand what “Shot to Win” messaging would do to Republicans’ willingness to vaccinate (given that Republicans were so much less open to the vaccine than Democrats at the time).

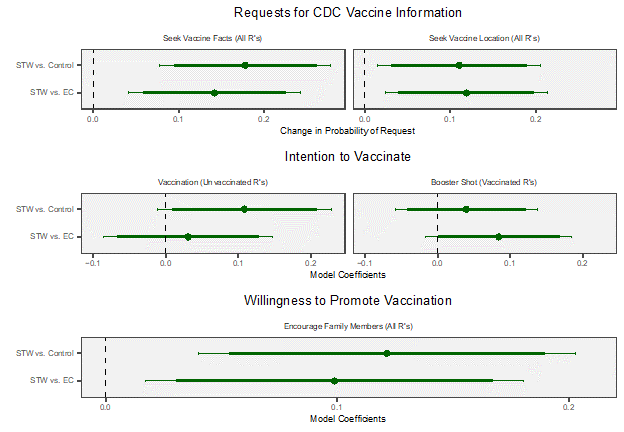

In each panel of Figure 1, the upper green bars show the experimental effects of the “Shot to Win” (STW) treatment relative to the pure control group (that received no message). In the lower green bars of each panel, we see how Republicans reacted to “Shot to Win” relative to the basic elite cue (EC) message. Bars that fall to the right side of the vertical dashed line show evidence of a positive effect for our treatment on the outcome.

Figure 1 – Effects of “Shot to Win” messaging vs. other treatments, among Republicans

For most of the tests we conducted, “shot to win” (STW) produced a large and statistically significant improvement in vaccine intentions for Republicans relative to the control (the top bars in each figure). But more important for our theory, STW also produced a larger effect than the EC message. The results show, for instance, a 12 percentage-point increase in Republicans’ willingness to encourage their relatives to get vaccinated relative to the Control, and a roughly 10 percentage-point increase relative to standard elite cue messaging. We also found strong effects on Republicans’ willingness to request more information about the COVID-19 vaccine (which we provided to them at the end of the survey (if they requested it)).

Negativity for public good?

Our results are good news for public health advocates seeking to boost vaccination rates. They also hint at the broader possibility that negative partisanship can be used in service of other socially positive agendas, especially when other methods (e.g., broad public appeals about the health benefits of vaccination, monetary incentives, etc.) no longer appear to work.

Electoral loss activates deep anxieties among partisan adherents, leading them to consider behaviors that they might otherwise avoid. The test case in the present study—the COVID-19 vaccine—was unique due to its urgency and large partisan gap. But our approach can be applied in other cases where partisans are disinclined toward a particular behavior. If officials can pit losing elections—which partisans really, really don’t want—against the desired behavior in question, our research indicates that partisans may indeed warm up to the lesser of two evils.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Politics, Groups, and Identities: ‘Partisan solutions for partisan problems: electoral threat and Republicans’ openness to the COVID-19 vaccine’ in Politics, Groups and Identities.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dE1