Recent decades have seen a move from cash to cashless payments in both Europe and the United States. Barbara Brandl writes on how the ‘abolition of cash’ has had dramatic impacts on many people’s economic lives. She writes that the emergence of cashless payments has blurred the lines between payments and consumer credit, which can aggravate existing inequalities for those on low incomes. In the US, those on low incomes often face high overdraft rates or are even excluded from the formal banking system altogether.

Recent decades have seen a move from cash to cashless payments in both Europe and the United States. Barbara Brandl writes on how the ‘abolition of cash’ has had dramatic impacts on many people’s economic lives. She writes that the emergence of cashless payments has blurred the lines between payments and consumer credit, which can aggravate existing inequalities for those on low incomes. In the US, those on low incomes often face high overdraft rates or are even excluded from the formal banking system altogether.

Until 2020, the most valuable financial sector company was always a bank. That year, the credit card company Visa finally overtook the mighty JPMorgan Chase and became more valuable than the top European banks combined. What happened? How did payments, traditionally the least profitable business area in the financial sector compared to investments and asset management, become so lucrative?

This development’s origin goes back to the gradual replacement of cash by cashless payment alternatives. Unlike what most people believe, the rise of cashless payments is more than a simple switch to a new (digital) payment medium. The public debate about the ‘abolition of cash’ has been lop-sided, and most critics have focused mainly on the danger of big tech companies gaining access to sensitive data. However, the rise of cashless payments has many other dramatic effects on modern societies’ economic lives.

Digital payments impact our everyday lives.

The digitalization of payments has enormous potential to increase social inequality further. However, the extent and significance of new payment dynamics in social inequality have been overlooked. Access to the payment system is existential in modern societies. Anyone excluded from the infrastructure through which most daily transactions are processed – such as buying food or being paid for work – is excluded from society. Traditionally, most individuals accessed payments through cash – the original infrastructure that enabled citizens to use markets. Importantly, cash payments are supported by a public infrastructure of bills issued by a central bank, which bears all the costs of establishing and maintaining the cash network (such as printing forgery-proof notes and distributing them). Cashless payments, in contrast, depend on networks of private payment providers, such as banks or credit card companies. Thus, the switch to digital payments implies a replacement of a public infrastructure with a private one. Replacing public payment infrastructure with private one has one severe consequence: while no one can be excluded from using cash, private payment providers can impede individuals’ access to cashless transactions or charge them high costs for their services.

Turning payments into profits – the emergence of the payment industry

The gradual replacement of cash with digital alternatives has created a fast-growing payment industry. This industry took off in the late 1950s when advancements in data processing led to the emergence of credit card companies, which are now the dominant actors in the payment sector. A second wave of digitalization began in the 2010s when a range of new private players (from mobile phone providers to start-ups and tech-driven payment companies like Google and Apple) significantly increased the industry’s profit potential, making the sector more attractive.

The emergence of cashless payments transformed the payment industry, leading to a sharp increase in profit prospects. The main reason behind this increase in revenues was that digitalization transformed the act of payment and linked payments to credit creation. In contrast to cash payments, where payment and credit are strictly separated, cashless payments – such as credit cards – can always be interwoven with consumer credit, accentuating and perpetuating social inequality. In other words, since cashless payments link payments to credit, everyone who executes a cashless payment is a potential loan recipient with less favorable terms. Moreover, contrary to other forms of credit (such as mortgages linked to property and used by high-income individuals seeking to enhance their wealth), consumer credit is mainly used by those on low incomes, who only have access to cashless payments and consumer credits under poor conditions. Therefore, these credits worsen the borrower’s already precarious situation.

While the link between payment and consumer credit was established during the first wave of digitalization, the second wave opened another source of income for private payment providers: the exploitation of the data generated in the payment process. Today, this data is a commodity that can be collected and sold to individuals and companies. Payment data is not only chased by advertising companies but also by companies in the financial sector seeking to create financial products tailored to user’s creditworthiness. In the Anglo-American countries, for example, subprime credit cards emerged, companies that charge consumers up to 30 percent interest on overdrafts. To make matters worse, the steadily growing share of cashless payments and the expansion of digital financial services in countries of the global South have recently reinforced inequality dynamics in those areas of the world where individuals are already vulnerable to indebtedness and poverty.

Photo by Blake Wisz on Unsplash

The regulation of digital payments

The socio-economic consequences of the payment sector’s digital transformation are not predetermined but can be shaped by political regulation. The importance of regulation becomes clear when looking at how different countries have followed different pathways to regulate cashless payments. One essential element in preventing harmful payment dynamics and minimizing the adverse socio-economic consequences of the digital transition is to legally restrain how much revenue digital payment providers can impose on customers. While in most Asian countries, for example, merchants siphoned most revenues, the situation is different in Europe and the United States – where consumers must pay to access digital payment infrastructure.

Consumers’ costs to access digital payments differ strongly between the United States and the Euro area. In the United States, the revenues earned by the payment industry are exceptionally high, amounting to $1,300 per person per year. Conversely, the revenues earned by private payment providers (banks, credit card companies, and start-ups) are relatively low in the Euro area. They vary between USD $250 in the Netherlands and USD $600 in Spain (Germany USD $300, France $400).

In sum, European payment companies only earn a quarter to half of the profits of their counterparts in the United States. A critical factor that explains the differences in profits between the two areas is the interest rates charged on overdrafts. While in the Eurozone, the interest charged to overdrafts is around eight percent, they average almost 20 percent in the USA. Moreover, overdraft interest can be as high as 30 percent in the case of subprime credit cards – a form of credit card that doesn’t exist in the Euro area (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Credit card interest rates, June 2010–February 2023

Data sources: For the US (national average and bad credit): Dilworth and Tang, 2023; for the euro area: Knops and Fromm, 2022; for Euribor: ECB, 2023a; for USD Libor: ECB, 2023b.

Can we shape payments? Comparing the United States and the Eurozone

In addition to the inequality dynamics associated with credit card debt discussed above, another important driver of social inequality within the payment industry is the exclusion of entire population segments caused by the formal banking system. This problem is severe in the United States. In 2021, five percent of households in the United States were unbanked – meaning no one in the household had access to a bank account. Meanwhile, 14 percent of US citizens are regarded as underbanked – which means that they use payment services outside the formal banking system at least once a year. The bottom line is that the US banking system does not meet (or only partly meets) the needs of almost 20 percent of the US population. Furthermore, the share of people wholly or partly excluded from the financial system differs according to race, education, and income. While only two percent of the white population does not have access to a bank account, over 11 percent of Black people and 9.3 percent of Hispanics are unbanked. The situation is worse if we take income into account.

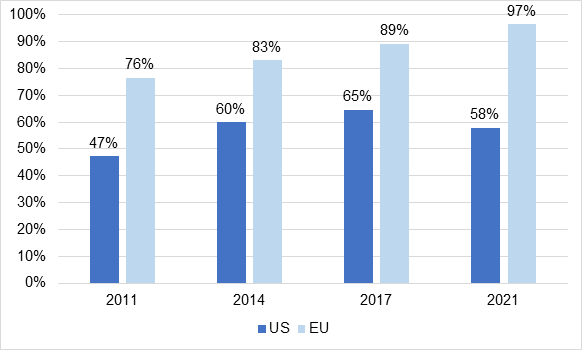

In the Euro area, the situation is quite different. In 2021, 99 percent of the population had a bank account. Access to financial services depends on one’s position within society to a limited degree. In Figure 2, we see the differences in bank account ownership according to a person’s level of education, which we use as a proxy for income.

Figure 2 – Bank account holders with primary education or less, USA versus euro area

Data source: The World Bank, 2022; own calculations.

US digital payment infrastructure supports European consumers.

The privileged position of European consumers regarding digital payments comes at a high price: dependence on US companies. The high profitability of the payment business in the United States has given rise to very successful credit card companies (Visa & Master Card) and start-ups (PayPal), which serve the European market as a kind of sideline. Meanwhile, the low-profit margins earned by European payment providers have made the business unattractive to the point where no European company had incentives to offer the infrastructure required for cross-border payments within the Euro Area. While there are national solutions within individual (large) countries – such as Girocard in Germany or carte bancaire in France – all cross-border payments within the Euro area are channeled through the infrastructure provided by US credit card companies: Master Card and Visa. American credit card networks not only pose a challenge to the relatively small cross-border payments market. They also threaten the national card systems supported by the public sector.

In the United States, large segments of the population are excluded from the banking system due to the digitalization of payments and the associated dominance of single credit card companies. In Europe, the exclusion of consumers is only a potential threat. A policy solution for such problems could be governments’ stronger engagement in providing public payment infrastructure. In the case of the US, greater protection for consumers by government is needed. The curbing of overdraft fees (a fee that comes on top of the interest on overdrafts) by the Biden administration in January 2024 is therefore a step in the right direction. In the case of the European Union, the development of a Digital Central Bank Currency (the Digital Euro) – a public infrastructure – is the only chance to fight consumers’ dependency on private companies that provide digital payments – an essential infrastructure of contemporary societies.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Small money, large profits: how the cashless revolution aggravates social inequality’, in Socio-Economic Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dHS