In the US Senate, lawmakers can use obstructive tactics such as the filibuster and invoking cloture votes to delay or force a vote on legislation. To examine how Senate bargaining can act as a signal to party constituents, Dan Gibbs builds a model of the Senate lawmaking process which also considers parties’ concerns about policy outcomes and their reputations. He writes that the cost of obstruction is key to its signaling function to party constituents.

In the US Senate, lawmakers can use obstructive tactics such as the filibuster and invoking cloture votes to delay or force a vote on legislation. To examine how Senate bargaining can act as a signal to party constituents, Dan Gibbs builds a model of the Senate lawmaking process which also considers parties’ concerns about policy outcomes and their reputations. He writes that the cost of obstruction is key to its signaling function to party constituents.

The filibuster is a parliamentary procedure in the US Senate in which a Senator speaks for an extended period to delay or block a vote on a bill. It is often associated with the requirement for a supermajority vote (60 out of 100 senators) to end debate and proceed to a vote on the legislation, a process known as invoking cloture.

While filibusters and invoking cloture can be viable policymaking tactics for a party that believes it can wait its opponent out, the fate of a bill in the Senate is often known in advance of a filibuster or cloture vote. In 2021, for example, majority leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat from New York state, introduced the For the People Act (an election reform bill) despite having the support of only 50 senators. In response to a Republican filibuster, Democrats held a cloture vote. As expected, the motion to end debate did not pass with all 50 Republicans voting to continue.

What explains such legislative episodes in which time and effort are expended on hopeless bills? A common explanation is that Senators engage in obstruction as a messaging strategy to signal to their base that an issue is important to them. Although this function of obstruction is widely accepted, it is not systematically incorporated in existing theories of US lawmaking. I developed a model to better understand how the dynamics of reputation intersect with legislative bargaining and obstruction to shape the strategic behavior of Senators and their parties.

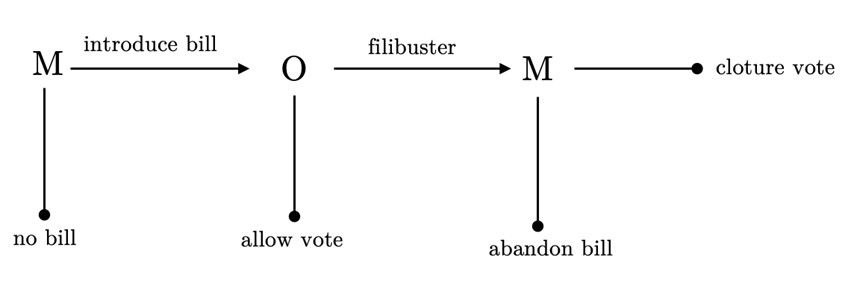

Model of legislative bargaining.

My model looks at the bargaining interaction – what political scientists call a “game” – between a majority party (M) and an opposition party (O) with opposing policy preferences and is shown in Figure 1. First M decides whether to introduce a bill. O then either filibusters the bill or allows it to pass. The policy implications of allowing the bill to pass depend on whether government is unified (when the president’s party also holds the Senate and US House of Representatives), in which case the policy is likely to become law, or divided, where it is likely to be vetoed. If O filibusters, M decides to abandon the bill or attempt cloture. I focus on cases in which any attempt to invoke cloture is known to be futile.

Figure 1 – The legislative bargaining sequence.

Each party represents a core primary constituency. Constituencies observe the bargaining that is occurring and learn about the priorities of the incumbent Senators. Parties want their constituency to view them favorably to avoid primary challenges. In the interest of gaining seats in general elections, they want the other party to be viewed poorly by its own constituency.

The cost of obstruction depends on a party’s policy priorities.

Filibusters and cloture votes impose costs on parties by consuming valuable legislative time. If this cost is sufficiently high, a party is unwilling to engage in obstruction unless the issue is a top priority.

Only a party knows its own true policy priorities. This has implications for legislative bargaining. For example, the opposition may threaten to filibuster but be unwilling to go through with it due to the cost. This can compel the majority to call its bluff by introducing a bill.

Obstruction is an effective message because it is costly.

Constituencies of voters need evidence, not mere words, that a party shares their values. The costliness of obstruction is key to its credibility as a message. If obstruction impedes progress on another policy issue enough that Senators who prioritize a different issue are unwilling to engage in it, then obstruction conveys real information.

How do purely policy-motivated parties act?

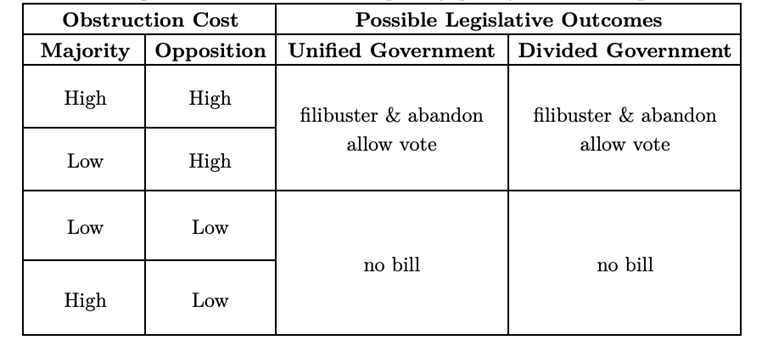

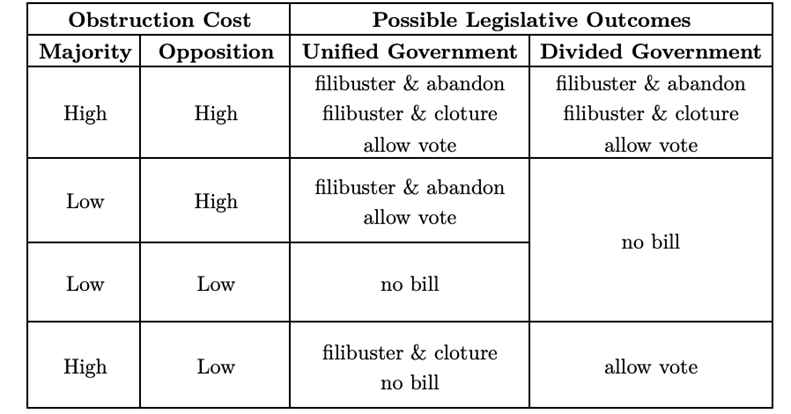

As a benchmark for understanding how reputational incentives affect lawmaking in the Senate, Table 1 lists all possible outcomes when parties only value policy.

Table 1 – Legislative outcomes with purely policy-motivated parties

Since the opposition allows the bill to pass only if the cost of filibustering is high and the policy issue is low priority, the majority introduces a bill only if the cost of filibustering is high. If it turns out that the issue is a high priority to the opposition, the majority abandons the bill rather than hopelessly attempt to defeat the filibuster.

“Filibusters Waste Time” (CC BY 2.0) by soukup

Concerns about reputation make parties adopt different tactics.

There are three ways in which senators strategically adjust their behavior due to reputation.

- The majority baits the opposition into filibustering so it can use cloture to send a message to its constituents.

- The majority leaves viable bills off the agenda to prevent the opposition from messaging with a filibuster.

- The opposition allows a vote to prevent the majority from using cloture to message.

These strategic behaviors change the predictions of the pure-policy model in several ways, displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 – Legislative outcomes when parties value reputation

Notice the difference between Tables 1 and 2 when the cost of obstruction for both parties is high. The opposition filibusters only if the policy under consideration is a high priority and the filibuster credibly conveys this. Although introducing a bill enables opposition messaging, a filibuster provides the majority with a platform to send a message of its own. This combined with the possibility of a policy victory compels the majority to introduce a bill as in the pure-policy model. Unlike the pure-policy model, cloture votes now occur.

Next suppose the cost of filibustering is high but cloture low. Without the ability to send a message via cloture, the majority faces a dilemma when deciding whether to introduce a bill. A policy victory is possible, but a policy defeat comes with the added cost of allowing the opposition to message. It takes this risk only under unified government. Under divided government, a veto is likely to erase the policy victory.

The opposition faces a similar dilemma when the cost of filibustering is low and the cost of cloture high. A filibuster hands the majority a messaging opportunity while conveying nothing about its own priorities. It filibusters only under unified government where it stands as the last line of defense against the policy.

If the cost of obstruction for both parties is low, reputation has no effect on strategic behavior. Parties act as if they were purely policy motivated because obstruction does not convey information about their priorities.

Implications for filibuster reform

The cost of obstruction is key to its signaling function. By characterizing how Senators strategically interact under different cost conditions, the theory raises new issues to consider when discussing filibuster reform.

Reforms intended to reduce obstruction by raising the cost (such as a return to the “standing filibuster”) may have the unintended effect of making obstruction a more effective signaling device. Moreover, a reduction in the number of filibusters following such a reform should not immediately be taken as evidence of success. Anticipating a messaging spectacle, majorities may leave agenda items off the table that they otherwise would attempt to pass. Conversely, changes to the rules that reduce the cost of obstruction (such as the adoption of the “tracking system”) may reduce its effectiveness as a messaging strategy and encourage Senators to act on policy motives.

Finally, the theory suggests a potentially desirable feature of obstruction. By providing Senators with a credible means of revealing their policy priorities, the filibuster enables citizens to learn valuable information about their elected representatives.

- This article is based on the paper ‘The Reputation Politics of the Filibuster’, in the Quarterly Journal of Political Science.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dLP