Visiting Fellow and women’s human rights lawyer Gema Fernández Rodríguez de Liévana makes the case for a gender perspective to be applied to legal procedural rules.

This piece reflects on how laws regulating procedural issues, such as admissibility can hamper women’s access to justice. It will be followed by further posts, which focus on the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s decision in X and Y v Georgia and analyse its reasoning on admissibility in the light of other treaty bodies’ practice. By examining this topic in three posts I hope to illustrate how decisions made at each stage raise distinct and overlapping issues impacting women’s access to justice.

The right to access to justice for women is “essential to the realization of all the rights protected under the CEDAW Convention” as stated by the Committee’s General Recommendation No. 33 on women’s access to justice. According to this GR, there are six interrelated and essential components —justiciability, availability, accessibility, good quality, provision of remedies for victims and accountability of justice systems— that are necessary to ensure access to justice.

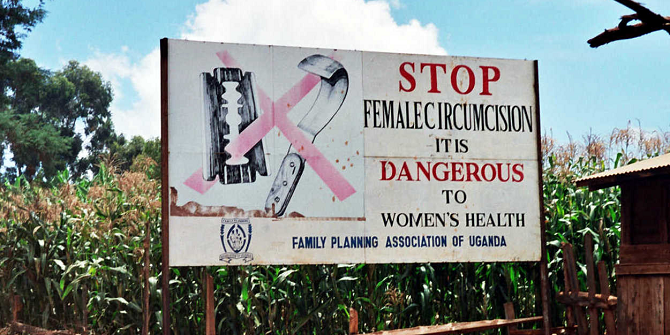

by Michael Coghlan (own work) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via flickr

However, women are denied justice in a number of ways. Sometimes it is through discriminatory substantive laws and other times it is due to “less visible obstacles” (see Beth Van Schaak’s work on this). In the former scenario, laws discriminate against women when they provide for a different, disadvantageous treatment in some circumstances with the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise of their rights (for an in-depth study on this, see Project on a Mechanism to Address Laws that Discriminate Against Women). The existence of these types of laws amounts to so-called de iure (or ‘de jure’) discrimination. In the latter scenario, the less visible obstacles can manifest as myths or as wrongful and harmful stereotyping on the basis of gender (see the cases of Karen Vertido v The Philippines or Ángela González v Spain) or they are the result of the application of procedural rules. These are forms of de facto discrimination.

Significantly, it is easier to identify gender bias leading to sex discrimination in substantive laws than in laws regulating procedural issues. This is usually because procedural laws are thought to be guided by the principle of neutrality and because they regulate formal aspects of the proceedings (such as standing, jurisdiction, representation, deadlines, time limits, length of proceedings or the standard of proof). The feminist legal critique of the “neutral” nature of procedural law builds upon the masculine construction of the law itself and how legal proceedings have consequently been designed taking the experiences and circumstances of (white, middle-class) men as universal. In this circumstance, mainstream legal doctrine and theory have been rendered incapable of adequately recognising women’s needs or incorporating women’s experiences. The application of a gender perspective —that uses gender as a central category of legal analysis— to the interpretation of the law reveals the fallacy of neutrality.

For example, some feminist scholars have drawn attention to how procedural and evidential rules operate negatively to impact women in prosecution of sexual violence cases. Whenever Criminal Codes and Criminal Procedure Rules consider elements such as the behaviour of the woman to qualify as rape –or the debate on rape being about force or about lack of consent—the standard of proof will differ, having an impact on the conviction rate. Recourse to the ‘behaviour element’ can also be seen in the case of X and Y v Georgia (posts forthcoming), where the Prosecutor’s Office declined to open a criminal investigation into an incident of violence because the victim had withdrawn her complaint.

Procedural rules are important because they act as gatekeepers to decisions being made. Many important cases are not heard due to jurisdiction and admissibility. For example, in the case of Marshall Islands v India on obligations concerning negotiations relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race and to nuclear disarmament, the International Court of Justice decided that it had no jurisdiction to consider the questions that were brought before it.

When looking into the right to access to justice for women of colour, women from ethnic or other minority groups or women in vulnerable situations (such as trafficked women or asylum seekers) the idea of the neutrality of the procedures is particularly challenged. Women of colour have contributed to legal feminism by raising concern for the way mainstream feminist discourse was predicated upon and thereby privileged the experiences of white women. “Just as women’s experiences were overlooked through the ‘universalisation’ of men’s, so also were the experiences of women of colour eclipsed by feminist attendance to white women’s interests and concerns” (see Intersectionality and Beyond: Law, Power and the Politics of Location). The term ‘intersectionality’ has demonstrated the need for a ‘holistic approach’ in the determination of the right to be free from discrimination and violence (see Towards Intersectionality in the European Court of Human Rights: The Case of B.S. v Spain). In B.S. v Spain, the European Court of Human Rights considered that Spanish courts “failed to take account of the applicant’s particular vulnerability inherent in her position as an African woman working as a prostitute”.

Admissibility was at the core of the Strasbourg Court’s decision on the case of G.J. v Spain. This case concerns a Nigerian woman who had been trafficked to Spain and subsequently sexually exploited for four years. She claimed asylum on two separate occasions. First, when she arrived in the country, she claimed that she had been persecuted in Nigeria for religious reasons. Her application was dismissed. Second, when she was in an immigration detention centre pending deportation, she filed a second asylum request as a victim of trafficking that was subsequently dismissed (a commentary of the decision can be found here). Simultaneously, she was receiving support from an NGO and had instructed them to apply for a reflection period for her (under article 13 of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings), signing a written authority to act. Days after, she was deported. The proceedings before the national courts focused on whether the NGO had standing to litigate the case. The decision, where the Court held that the organisation had no standing to lodge the application, has been said to show “many of the problems victims of human trafficking encounter to access justice” in one of those cases “where formalities swallow justice” (see G.J. v. Spain and Access to Justice for Victims of Human Trafficking).

Experience from the practice indicates that the Committee is likely to be presented with cases in similar circumstances, where regional courts or bodies without a specialism in gender may have previously found the cases inadmissible. Therefore, it is extremely important that the Committee continues to apply a wide interpretation of admissibility issues that incorporates a gender lens into procedural requirements. The Committee is in an exceptional position to reveal the way in which the lack of compliance with these requirements is often directly linked to obstacles, visible and less visible, that women face to enjoy their right to access to justice.

More from this series

- How a case against Georgia strengthened international standards for tackling violence against women

- What is considered the ‘same matter’, matters for women seeking justice

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

Image credit: Pascal Bernardon on Unsplash