With the advent of the WPS agenda, gender-based violence (GBV) has been increasingly examined in relation to conflict, state stability, and human security. Recognition of human trafficking as a pressing humanitarian issue has also progressed, at the same time that the trafficking industry itself has continued to grow.

Academic and policy works often address trafficking within the wider context of conflict-related GBV more generally, or, paradoxically, as an entirely separate issue (although recent LSE work has highlighted that legal regulation of these issues, despite long having “followed separate tracks,” are “newly associated through the [UNSC’s] recognition that [both] come within the Council’s responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security”). However, Darcy McConnell argues that trafficking of women and girls in fact constitutes a distinct form of gender-based violence, and that prevalence and tolerance of trafficking is intricately entwined with issues of security.

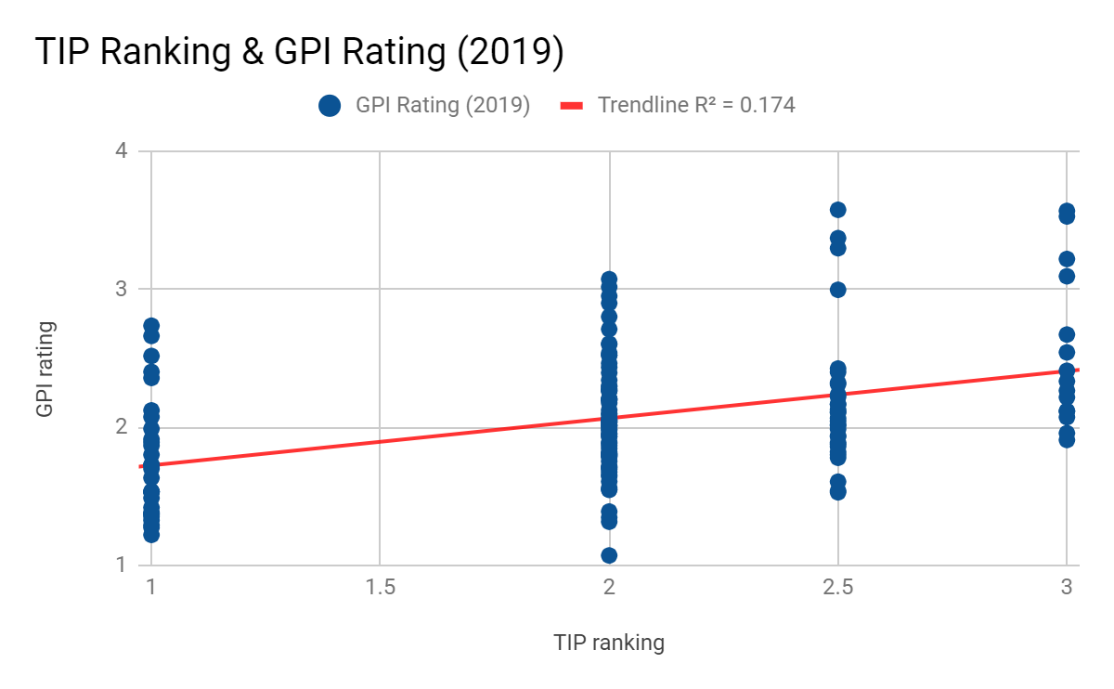

Accurate statistics on trafficking and peacefulness are notoriously difficult to obtain. However, existing data suggests a positive relationship between greater stability within states and lower levels of trafficking to, from, and within those states. Analysis of the U.S. State Department’s 2019 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report and the 2019 recent Global Peace Index (GPI) Report , for instance, shows moderate correlation between a country’s placement on a higher TIP Report tier and a higher rating for that country in the GPI report, with a correlation coefficient of 0.417 (see tables below).

Previous years’ data show similar correlations. Valerie Hudson’s Scale of Trafficking rankings also measure trafficking prevalence by country; analyses of this data from 2011 and 2015 show an even more significant positive correlation between higher Scale-of-Trafficking rankings and higher GPI ratings, with a correlation coefficient of 0.630 (see tables below), and significant differences in mean GPI scores between Scale of Trafficking tiers. Interestingly, while the correlation between TIP tier and GPI rating has decreased slightly (from 0.471 in 2018 and 0.538 in 2017), the correlation between Scale of Trafficking ranking and GPI rating has increased, from 0.458 in 2011. Because the Scale of Trafficking is based on information about the trafficking of women and girls specifically, one potential implication of this data is that trafficking of women and girls specifically is more closely intertwined with lack of peace or stability than trafficking overall; however, such a claim is outside the scope of the rudimentary analysis here.

The relationships between trafficking and societies’ levels of insecurity are multifaceted and multidirectional; trafficking activity is obviously not the sole or main cause of conflict or insecurity. However, the analysis mentioned above, as well as qualitative evidence outlined below, supports the idea that prevalence of trafficking is linked with insecurity in several ways.

Trafficking and security are intricately connected when it comes to the creation of vulnerable populations. Armed conflict and insecurity–including not just warfare or terrorist activity but, for instance, gang violence–leads to an increase in refugees, internally displaced persons, and stateless persons. Women and girls make up about half of these groups and are frequently more physically and economically vulnerable than their male counterparts, which places them at greater risk of being trafficked; trafficking and instability are not connected only to the creation of vulnerable groups, but disproportionately affect those who are already in vulnerable positions. For instance, in dire situations, parents may see putting their children in scenarios ripe for trafficking, such as risky migration, or entering their daughters into forced marriages as ways to keep their children safe—or, at least, safer. (In Syria, for example, rates of child marriages have greatly increased since the onset of the civil war.)

Perhaps the most obvious link between conflict and trafficking concerns the trafficking of women and girls by armed actors. It is widely acknowledged that gendered violence is used as a weapon of war, but trafficking of women and girls is often rhetorically conflated with “rape as a weapon of war” or GBV more generally. I argue that trafficking of women and girls constitutes a distinct form of strategic gender-based violence in the context of conflict, with distinct security implications. Like rape and torture, the trafficking and enslavement of women and girls (which does nearly always include rape and sometimes torture) can be used to terrorize a society, tear the social fabric of a populace, defeat or wipe out an enemy population, or clear a targeted territory—but it can also be used to finance, recruit, and continuously, materially aid armed groups.

Accurate statistics on trafficking and peacefulness are notoriously difficult to obtain. However, existing data suggests a positive relationship between greater stability within states and lower levels of trafficking to, from, and within those states

Trafficked women and girls can continually provide sexual gratification; they can be forced to do chores, to undertake dangerous tasks such as de-mining (during Sierra Leone’s civil war, for instance, women forced into marriage and sexual servitude were used for this purpose), or to fight on the armed group’s behalf (up to 40% of child soldiers are girls). The promise of a “wife” or a female slave can be a powerful recruiting tool (ISIS, for example, recruits using enslaved girls and women as incentive); the services of trafficked women and girls may also be used to placate or motivate those who already belong to an armed group.

Trafficking in women and girls also generates funding for armed actors. It is a vicious cycle: armed conflict increases demand for trafficked women and girls, and the trafficking and servitude of those women and girls directly enables parties to more easily carry out armed conflicts, through the manpower, sexual and domestic work, and financial gain that they provide. The trafficking of human beings is not an incidental part of conflict; conflict demands it and it drives conflict in return.

Corruption and organised crime constitute another element linking state instability and the trafficking industry. Human trafficking is enormously profitable and involvement in trafficking has been linked to national and international organised crime groups, insurgent and guerrilla groups, and terrorist groups. Corruption in ostensibly stable countries can also enable trafficking in “unstable” countries in cases where victims are transported across international borders.

Evidence also links trafficking operations worldwide to military and border personnel, law enforcement, and government officials. In fact, corruption is necessary for the trade in women and girls to flourish and constitutes a driver of the industry; there is even evidence that, in certain regions, trafficking profits are used for political gain. This is extremely troubling for obvious reasons. Corruption of officials represents an enormous threat to stability: it undermines rule of law, subverts government legitimacy, and jeopardises both the hard security of the state and the human security of its citizens.

Trafficking of women and girls can remain a concern in post-conflict settings, and corruption exacerbates the issue in these contexts. An influx of peacekeepers—mostly male, mostly former or current military or police, many independently contracted—increases demand for sex work, a demand that can be met in part through human trafficking. The inherent precariousness of transitional societies, as well as an increase in the percentage of vulnerable women and children during and after conflict, creates conditions ripe for the growth of sex trafficking and other forms of sexual exploitation in areas with large populations of military and peacekeeping personnel. In fact, cases have been documented in which peacekeepers have knowingly participated in trafficking and sexual exploitation in post-conflict situations. This has clear negative implications for the establishment of lasting, positive peace and genuine human security in post-conflict societies.

Given the relationships outlined above, the trafficking of women and girls deserves greater attention as a standalone security issue. It is not only a symptom and outcome of insecurity and conflict, but also an active driver of insecurity and conflict; it can be a dimension of conflict-related GBV more broadly, but it can also serve as a distinct tactic of war, with security implications and consequences that differ from those presented by other types of gender-based violence—and may contribute more directly to the proliferation of armed conflict and state instability. Aside from obvious humanitarian concerns, the international community should devote more consideration to the interactions between the trafficking industry and issues of “hard security,” and recognise trafficking as a potential security threat.

This blog was written with the support of a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494).

Header image credit: Nico Schroeter (CC BY-ND 4.0)

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.