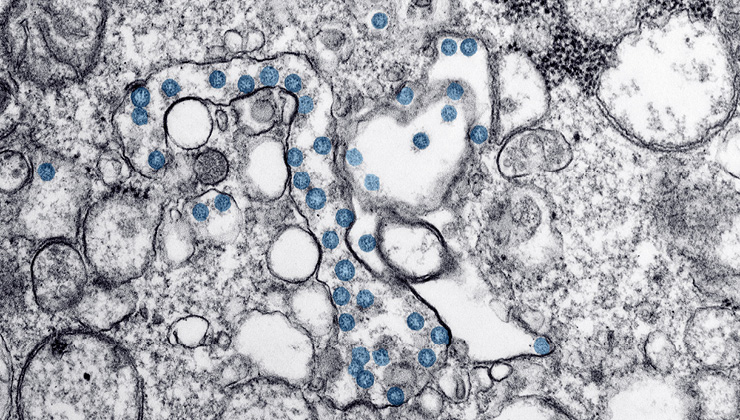

The COVID-19 crisis has brought much attention to domestic violence, but why has this invisible pandemic not been addressed before now? Maria Luísa Moreira looks at the denial by EU member states of the structural gendered inequalities in our societies that have led to alarming domestic violence figures and calls for greater recognition of, and action against, everyday experiences of gender-based violence happening behind closed doors.

Domestic violence has historically and universally been a pandemic hiding in plain sight, with most governments doing little or nothing to address violent abuse that happens behind closed doors. However, despite deeply rooted doctrines about the privacy of families and homes, domestic violence has been a well-known fact for decades that affects people in virtually every country.

In a change of events, an increasing number of reports on the rising incidence of domestic violence surged as COVID-19 reached all four corners of the world, rendering some visibility to this problem. Women’s human rights organisations, who have direct contact with the victim-survivors, often the first responders providing advice and practical support, have raised the alarm. Joining their momentum, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called for the prevention of domestic violence to be included in every country’s COVID-19 emergency plans. The current visibility being rendered to domestic violence is necessary but raises questions on why governments couldn’t have addressed this pandemic before – and indeed, what will be done to address it when the COVID-19 crisis is over, now that the need for effective action has been demonstrated even more clearly.

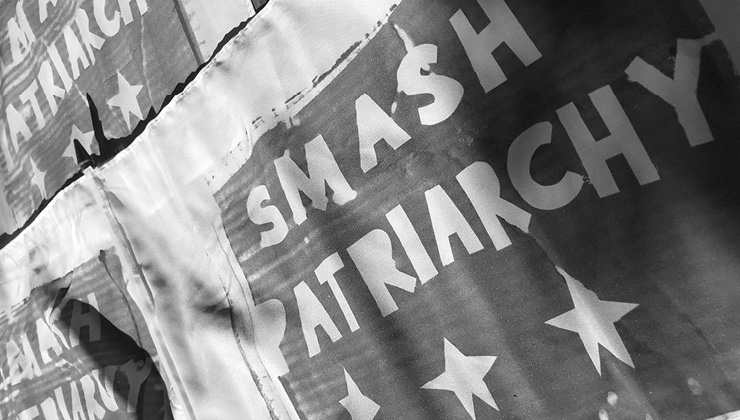

Violence and visibility: what is seen, and when?

For nearly twenty years, the Women, Peace and Security agenda has called for women’s issues to be seen and heard in the international arena. As argued by feminist literature, although this visibility has raised the profile of some issues, it has inadvertently overshadowed others. For instance, conflict-related sexual violence has gained hypervisibility over the years, scoring five Women, Peace and Security resolutions solely focused on the protection of women and girls in conflict-ridden regions.

However, other crimes of gender-based violence, often more frequently committed in all countries both in conflict and in peacetime, have otherwise been overlooked. These include, but are not limited to, domestic violence, human trafficking and female genital mutilation – all transnational and highly prevalent in high, middle and low-income countries, including within so-called ‘peaceful’ EU borders.

Because it has traditionally been labelled as a private issue, domestic violence has widely been neglected in international law and policy and excluded from debates and normative standards about what constitutes prevention and protection from domestic violence, save for the Istanbul Convention. Last year, however, UNSC resolution 2467 on Women, Peace and Security potentially paved the way for change by introducing the idea of continuums and calling for links between in conflict and non-conflict contexts to be made. Similarly, despite the general invisibility it has been rendered in international policy so far, the COVID-19 crisis seems to have also ignited some potential change. Since the beginning of the virus outbreak, reports of domestic violence have increased hugely and, in some cases, this growing abuse against women has culminated into an alarming incidence of femicides throughout the isolation period.

conflict-related sexual violence has gained hypervisibility over the years, scoring five Women, Peace and Security resolutions solely focused on the protection of women and girls in conflict-ridden regions. However, other crimes of gender-based violence, often more frequently committed in all countries both in conflict and in peacetime, have otherwise been overlooked

COVID-19 has so far been deadlier for men, but lockdown measures have victimised women the most. As a response to these warning signs, awareness strategies and temporary solutions have been implemented in some countries: For instance, the French and Italian governments advocated for discreet ways to ask for help at pharmacies and released a mobile app that allows victims to ask for help without having to make a phone call, respectively. In other cases, expert civil society organisations that currently run shelters and provide necessary services, such as helplines, have been calling for the allocation of increased investment and resources to meet the demand, but women are still being turned away. While it is important to highlight the interconnectedness of COVID-19 and domestic violence, as many governments have recently done, it will be equally important and urgent to acknowledge and act upon violence against women in its aftermath.

Violence and eurocentrism: women’s safety is endangered here, not just out there

Questions of visibility and western values of international security are mutually dependent insofar as this relationship influences what is included in policymaking and who is held accountable. Feminist scholars and practitioners have long urged world leaders to reform this relationship as it creates and sustains North versus South dichotomies, meaning that women’s issues in different countries are ineffectively contextualised and addressed.

For instance, scholars and activists have long raise concerns over the Women, Peace and Security agenda’s content (what counts as violence against women, who are the perpetrators and where) and its practical implementation by UN Member-States. These divides and dichotomies further reinforce western and colonial underpinnings of international security, leading to fallacious arguments for the protection of women and girls in so-called dangerous zones, but not in the developed world.

Western assumptions that egregious violations only happen out there – in conflict-ridden countries – are closely linked to ideals of eurocentrism and widely accepted views of the EU as an oasis of human rights and civil liberties. Although the EU has taken some action towards gender inequality, for instance in the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), less attention has been paid to country-level and EU-wide efforts to ensure the safety and protection of women and girls from violence specifically.

For instance, as of December 2019, the Istanbul Convention had been signed by all members of the Union, but ratified only by 21. This lag in ratification is justified because the Istanbul Convention is a relatively recent treaty and the Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) committee, which monitors its implementation, has only been operating for four years. However, while some degree of delay is normal for a new treaty, resistance to gender equality is a factor. GREVIO’s first general report analysed challenges emerging from member-states’ implementation of the Istanbul Convention and identified the outright denial of interlinks between structural gender inequalities and violence against women, which hinders the development of comprehensive policies, as a key barrier.

scholars and activists have long raise concerns over the Women, Peace and Security agenda’s content (what counts as violence against women, who are the perpetrators and where)... These divides and dichotomies further reinforce western and colonial underpinnings of international security, leading to fallacious arguments for the protection of women and girls in so-called dangerous zones, but not in the developed world

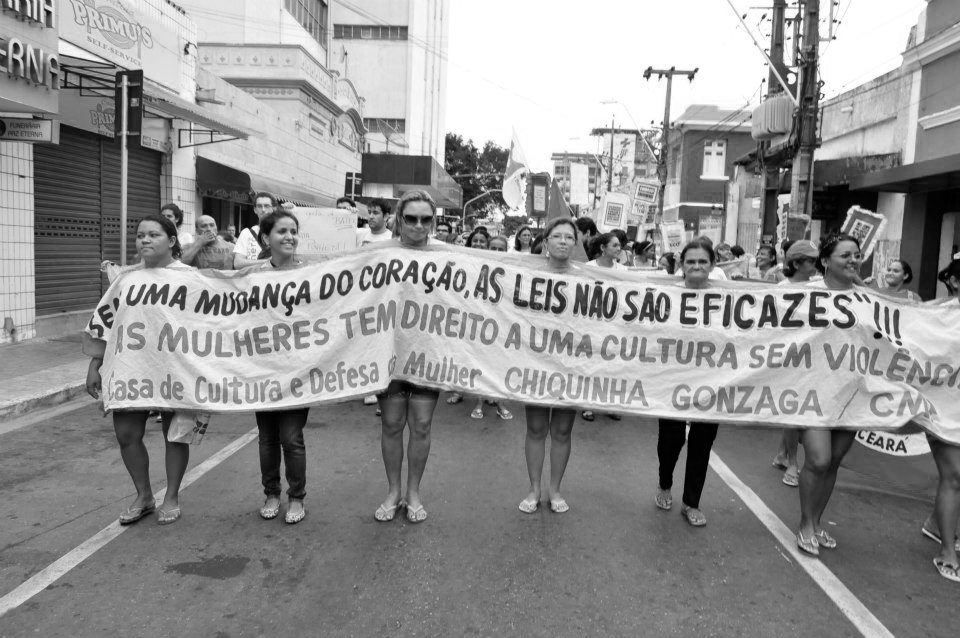

The existence of retrogressive sociocultural norms, attitudes and stereotypes impede not just the development and implementation of progressive legislation but also allow for the incidence of violence against women to thrive. In Portugal, a country often ranked at the top of the most peaceful nations in the world, at least 35 people died in 2019 as a consequence of domestic violence – 81% of whom were women. In France and Spain, the number of women who died at the hands of their current or former partners was, respectively, at least 116 and 55 for the same period.

Equally alarming figures are found in virtually every EU member state and yet, as it’s predicted, the great majority of cases never get flagged. However, as urged by civil society organisations, governments should be doing more than simply quantifying cases of domestic abuse – gathering data and analysing the history of cases is just as vital. This urgent prioritisation has also been highlighted, for instance, by the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women who proposed the establishment of “femicide watch” institutions to lead the gathering and analysis of data.

In fact, lack of comprehensive and comparable data is one of the main barriers to the eradication of domestic violence. Without up-to-date figures, disaggregated by gender, race and class, and analysed through an intersectional lens, the real scope of the problem will remain unknown. The last EU-wide survey on domestic violence was conducted in 2014, and was based on interviews with 42,000 women (1,500 per Member-State). This sample corresponds to less than 1% of the bloc’s total female population. The report that followed indicates that a third of women across the EU have experienced “physical and/or sexual violence by (non-)partners since the age of 15.” Needless to say, domestic violence figures within EU borders are alarming with or without COVID-19.

In fact, lack of comprehensive and comparable data is one of the main barriers to the eradication of domestic violence. Without up-to-date figures, disaggregated by gender, race and class, and analysed through an intersectional lens, the real scope of the problem will remain unknown

Thus, while country-level analysis of this survey raises concerns over which EU members have effective reporting mechanisms in place, the prevalence of violence against women in the bloc should be compared and assessed both on a case-to-case basis and the EU as a whole. Member-States’ arbitrary efforts, or lack thereof, must be monitored and incentivised by Brussels, and rules and sanctions prescribed by EU law. Now that the EU has signed the Istanbul Convention there could be some potential change in the horizon for a bloc-wide approach to violence against women, but guidelines for protection and prevention should also be prioritised by national legislation. These efforts have since been reinforced by European Parliament and Council’s Directive 2012/29/EU, which prescribes that victims of crimes, namely violence, must be given appropriate information, support and protection and be able to participate in criminal proceedings.

Violence post-COVID-19: What will remain (in)visible?

Band-aid solutions for the current peak of domestic violence surely are necessary but also far from being transformative in the long-term. Complete eradication of this hidden pandemic requires comprehensive reforms: improved political leadership, more funding and budget allocations, ensuring that victim-survivors can access the services they need to fulfil safety and recovery needs, ensuring that civil society organisations can provide these services and lead social change, implementing far-reaching monitoring mechanisms and structural reforms of criminal justice systems.

One must also question if societies run the risk that governments are concerned about domestic abuse within and only linked to the pressure to respond fully to a health pandemic, but once that is managed things may revert to the ‘same old’ approaches of before. What will remain (in)visible is dependent on governments’ approaches post-COVID-19 and so is the hope for transition from ignoring, not investing and tolerating men’s violence against women as a default norm of gender relations.

The issue with having poor EU-wide approaches to domestic violence, particularly through legally binding instruments and monitoring mechanisms, is that it leaves room for the 27 members not to prioritise its implementation domestically. This is of the utmost importance since experts have warned of the profound economic recession that will follow COVID-19, meaning that governments are even less likely to address gender-based violence.

This is both an egregious denial of women’s rights and a false economy, given the costs of violence against women at the individual and societal levels. For instance, a 2018 CARE report highlighted that violence against women costs society more than 2% of global GDP, and a 2014 EIGE report found that this violence within EU borders is a burden in terms of physical and emotional suffering and costs to the public purse related to health care, criminal justice and lost economic productivity.

Lastly, EU members must reflect on what will happen to the current visibility of domestic violence when the COVID-19 crisis is over – the virus will go away, but the same thing can’t be said about structural problems of gender-based violence. For the sake of victims and survivors, and to ensure humane societies where the physical and mental integrity of everyone, without discrimination, is a priority the EU must ensure domestic violence won’t again be rendered invisible.

Being a woman and an EU citizen, I dream of the day we will be living in, and proactively working towards a truly free, equal and tolerant Union – both in times of peace and crisis. A day when invisible violence against women, and governments’ inaction towards it, become a thing of the past.

Special thanks to Professor Aisling Swaine and Lisa Gormley for their invaluable comments and suggestions. There is no way this blog would have made it out of my desk without their encouraging words.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

Image credit: Joachim Laatz