In the WPS agenda’s twentieth anniversary year, New Directions brings academics, practitioners and activists into conversation in a book that demonstrates the evolutionary breadth and depth of WPS policy and scholarship. In the introduction to the volume, Soumita Basu, Paul Kirby and Laura Shepherd sketch the contours of the WPS agenda as something broader than the text of the policy frameworks that United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 instigated. They characterise the agenda as the focal point of a WPS community and as a site of political investments, demands and disavowals. The editors position the book in the “new politics of WPS…in relation to geographical, temporal and institutional scales” (p. 2) and map, as much as can be done, the trajectory of WPS in scholarly and policy fields: beginning as a feminist activist agenda at the margins of international security, to a policy agenda ingratiated in the ‘masculine’ space of the Security Council, to an agenda that is diffused outside of the politics of the Security Council in local and other institutional spaces (pp. 5-6).

The form that the contributions to this impressive collection take in themselves demonstrates a plurality of engagements with the WPS agenda. Some chapters are presented as academic papers, while others take the form of conversation between researchers, practitioners, and those who blur attempts to establish a firm distinction between the two. This shift between formats makes for compelling reading and invites the reader to reflect on what it means to practice WPS across a range of contexts. Together, the chapters demonstrate that the trajectory of the WPS agenda does not lend itself to a discrete or linear understanding, but rather that multiple actors are involved in shaping and contesting this agenda in parallel and in interconnection. A recurring theme then is of conceptualising WPS as contested, with boundaries that are both pushed and that push back. Overall the volume demonstrates that this agenda is best approached with conceptual complexity that discourages definitive pronouncements on what WPS is or is not, and who its proper subjects are.

A central point of contention, and one that has consistently remained since WPS’s inception, is what the agenda does in implementation. That is, what have been its productive capacities in the two decades since feminist anti-militarist activism succeeded in getting the Security Council to take seriously issues of women, peace and security? On this point the contributions give much food for thought.

Together, the chapters demonstrate that the trajectory of the WPS agenda does not lend itself to a discrete or linear understanding, but rather that multiple actors are involved in shaping and contesting this agenda in parallel and in interconnection.

On the one hand, the agenda has been ground-breaking in its insistence that women’s perspectives and participation matter in international peace and security. As Madeleine Rees notes in her conversation with Joy Onyesoh and Catia Cecilia Confortini, the agenda promises women a right to participation and provides “the opportunity…to reframe security…and bring the word ‘Peace’ to the forefront of the work” (p.244). This promise has not been inconsequential: Rita M. Lopidia recounts in her chapter with Lucy Hall how the South Sudanese women’s peace movement used Resolution 1325 as a tool to demand space at the peace table (p.31). Further, the agenda has made resources available for women’s organising – even when these women may be critical of some aspects of WPS policy, as Elizabeth Pearson shows to be the case with programmes to engage women in countering violent extremism. In short, the WPS agenda provides a basis from which women can articulate demands to be included and offers resources for organising.

At the same time, the productive nature of these promises is associated with a number of exclusions as to who or what falls within the purview of a WPS issue and thus what experiences are seen as ‘counting’ in the realm of international peace and security. In her chapter, Rita Manchanda underscores the importance of asking which women constitute the subjects of WPS, as she demonstrates the limited applicability of militarised security discourse to women’s peace movements’ concerns with human security in South Asia.

Gema Fernández Rodríguez de Liévana and Christine Chinkin reveal that trafficking has been left off the WPS agenda even though it is a significant gender-based violence concern in conflict and post-conflict areas, and demonstrate how this omission both contributes to and is a consequence of the fragmentation of women’s human rights agendas in international law.

Marta Bautista Forcada and Cristina Hernández Lázaro show that WPS has not accounted for the significant increase in private contractors engaged in peace and security work, meaning these actors are often not held accountable for the gendered harms they may commit.

Briana Mawby and Anna Applebaum argue that climate change, migration and climate–related migration all constitute significant (gendered) security threats yet remain at the margins of the agenda.

In these areas the institutional boundaries of WPS push back on feminist activism that seeks broader recognition of gender-based harms and the interconnections between varied experiences of violence and how they might be connected to global political and economic structures. WPS as an institutional policy field has proven reluctant to make space for critique of global hierarchies of power, imperial and neo-colonial practices, and how these produce the contexts in which women experience harm. On this point the conversation between sam cook and Louise Allen on “holding feminist space” provides a telling example on who or what is ‘allowed in’. They describe how Security Council members would request civil society representatives who could recount compelling personal accounts to speak, ones that “could ‘move’ the Council with their story” (p. 127), devoid of political analysis or demands:

…a diplomat relayed their ambassador’s request that I identify a civil society speaker who had either been raped or was born of rape, had lived through the stigma of their ordeal and had then risen to become a leader in their community (p. 127).

In other words, they expose how only those stories that “fit” gain purchase in halls of power and that these stories are used to consolidate, rather than divert, current modes of operation.

WPS as an institutional policy field has proven reluctant to make space for critique of global hierarchies of power, imperial and neo-colonial practices, and how these produce the contexts in which women experience harm.

The conversation between Minna Lyytikäinen and Marjaana Jauhola, reflecting on academic and civil society engagement in the drafting of Finland’s National Action Plan on WPS suggests that these institutional constraints are not unique to the Security Council, but are discernible in state structures that implement the agenda. They argue that the “consensus-driven gender equality policies of the neoliberal strategic state” hinder critical and radical feminist engagements with the agenda (p.84). These accounts raise concerns over “co-optation” and how narrow understandings of women, the violence they experience in conflict, and what they contribute to international peace and security discourse and practice have produced boundaries around WPS that could themselves be considered violent.

Alongside “co-optation” are critiques of how women are instrumentalised in WPS narratives. Consistent with gendered understandings of what women can do in peacebuilding and/or women’s roles in conflict, ‘women’ – as a flattened, homogenised group – have been added to international peace and security discourses to justify particular aims, often ones that subvert women’s human rights and protections issues.

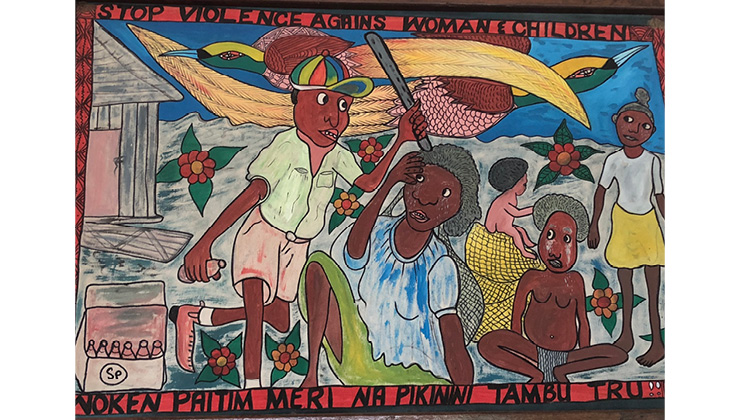

For example, in seeking economic solutions to conflict, Nicole George demonstrates how women have been marginalised from investments in economic peacebuilding yet subsequently incorporated into that narrative in ways that expound the benefits of women’s economic activity and engagement for broader aims of peacebuilding. Women, understood as inherently peaceful and in their role as family providers, will redistribute familial wealth and resources to ensure community stability and prosperity, it is argued, and thus gendered notions of women’s role in peacebuilding are perpetuated. Other contributions also raise serious and ongoing concerns regarding the instrumentalisation of women in countering violent extremism (CVE) discourse and thus in the securitisation of WPS/peace more broadly (Pearson; Fernández Rodríguez de Liévana and Chinkin).

Instrumentalisation, alongside other critiques of WPS, demonstrate as well how race and racist histories must be centred in understanding WPS. For example, it is important to pay attention not only to how ‘women’ are constructed and wielded in policy narratives but also which women, where and how, and what structural power is solidified in the process.

Contributions from Rita Manchanda, Toni Haastrup and Jamie J. Hagen, and Anna Stavrianakis make clear the need to decentre white Western agendas in any feminist approach to peace. The WPS agenda itself is situated in a global hierarchy of states in which it can and does act as a mechanism of policing and surveillance (p. 158). For example, Toni Haastrup and Jamie J. Hagen demonstrate how global racial hierarchies operate through WPS National Action Plans (NAPs); the NAPs of Global North states, they argue, “localise the WPS agenda externally”, overwhelmingly in the Global South. Global South NAPs, on the other hand, are more inward looking. They argue, therefore,

that that there is no accounting for how the historical and contemporary conditions of colonialism and its attendant racism manifest themselves in the current structure of the international system. It is this condition that renders the fragile ‘Other’ vulnerable enough to need the interventions being offered within Global North NAPs.

It is a mistake then in WPS implementation and analysis to take on gender first, then racial and post-colonial politics “as if these are successive issues to be tackled rather than cross-cutting and compounding ones to be addressed together. Gendered relations are always already racialized relations” (Stavrianakis, p. 154).

it is important to pay attention not only to how ‘women’ are constructed and wielded in policy narratives but also which women, where and how, and what structural power is solidified in the process

Taking imperial and colonial histories seriously and accounting for their ongoing ramifications in global systems of power means recognising how WPS itself reproduces inequalities, especially by trading in white saviour politics. Women (invariably the ‘poor Third World woman’ trope) are instrumentalised in and through WPS to solidify boundaries of where can be intervened in (Haastrup and Hagen), who intervenes and who is able to voice their needs and priorities in this space (Manchanda).

Moreover, contemporary feminist peace activism can and does perpetuate histories that are problematically bound up with colonial and imperial ideations. Contemporary support for non-violence can disregard the experience of militant women, for instance, and how armed resistance is an essential mechanism for individual and collective security in some contexts (Stavrianakis). Core to the critiques of WPS conceptualisations and implementation, as well as looking ahead to the new directions of WPS then, is the necessity of an intersectional understanding of both peace and gender.

While these remain important critiques, and issues that WPS will certainly need to reckon with, it is equally important to acknowledge and engage with the significant labour that occurs both within and outside institutional spaces to modify, implement and define WPS as an agenda and, ultimately, to build a more gender-just approach to and understanding of peace.

As the editors note, some of “[t]he most enterprising use of the WPS resolutions… has been on the part of civil society organizations…who have employed it to demand action from their governments and intergovernmental organizations such as the UN” (p. 7). For example, Lyytikäinen and Jauhola’s account recounts how their clash with the neoliberal state’s agenda prompted the creation of a virtual collective that articulated “alternative feminist politics” (p.89). Indeed, a number of chapters highlight the need for feminist coalitions in international peace and security and how the work of collectives and individuals is vital in acknowledging, understanding and bringing justice for gender-based harms both in and out of conflict (Viseur Sellers and Chappell; cook and Allen; Onyesoh, Rees and Confortini).

Core to the critiques of WPS conceptualisations and implementation, as well as looking ahead to the new directions of WPS then, is the necessity of an intersectional understanding of both peace and gender.

Taken together, the volume troubles the multiple boundaries that are drawn in and through WPS and their productive consequences, demonstrating a methodological breadth as well. Given the WPS policy aims and the theoretical tools used to examine them throughout, the volume is of interest to those working in gender, peace and security broadly, as well as feminist, gender and women’s studies.

Beyond this is the relevance of the volume to those interested in international peace and security, peacebuilding and conflict-resolution. The contributions consistently demonstrate how peace itself is produced, fluid and rooted in particular conceptualisations of politics, economy and society ‘as normal’. WPS was brought to the international policy agenda as women were so often marginalised from these understandings, but feminist activist, practitioner and scholarly work on and in WPS demonstrates how peace can remain exclusive, dominated by state interest and reproduce global systems of inequality, particularly where an intersectional lens is lacking.