Gender equality is an important principle in the German Government’s Strategy to Support Security Sector Reform (SSR). In order to put this into practice, the ministries involved need to go beyond agreeing on specific goals and measures that should be reported on within the framework of Germany’s new National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security. They must also confront conflicts in partner countries. Sensitivity to local context must not mean ignoring gender equality.

In the last three decades, Security Sector Reform (SSR) support has become an integral part of external statebuilding and democratisation efforts. SSR aims at creating effective and accountable security agencies that make democratic governance, sustainable political stability and human security possible. It encompasses far-reaching processes of institutional and social change, such as the reform of the military, police and the judiciary or the strengthening of democratic control of the security sector.

On the one hand, SSR is thereby seen as an opportunity to promote gender equality. On the other hand, it is argued that taking gender perspectives into account is a necessary condition for successfully implementing SSR. This can be illustrated using three central examples. First, women and LGBTQI+ persons in conflict zones are exposed to a higher risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) than men are. At the same time, it is often overlooked that men are also victims of SGBV. In order to move toward the goal of an effective, efficient and accountable security sector, institutions must therefore take into account the security needs of all genders.

Second, inadequate gender diversity in the institutions of the security sector contributes to a male-dominated organisational culture in which stereotypically “male” performance standards such as risk-taking and toughness are rewarded and deviations are sanctioned. SSR should thus always work to ensure that gender diversity is increased, even if this is only a first step toward breaking through patriarchal organisational cultures and power structures.

Thirdly, as an important contribution to prevention, SSR should also examine the deeper causes of SGBV and all forms of violence. These include, in particular, not innate but socially acquired concepts of masculinity that encourage violence. In security institutions, these can be countered through measures such as gender training, gender working groups and codes of conduct.

Gender in the new German SSR strategy

In 2019, the German Government agreed on an Interministerial Strategy to Support Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the Context of Crisis Prevention, Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding. The strategy introduces gender equality as a guiding principle and recognises that “effective and sustainable crisis and violence prevention is inconceivable without gender equality.” As part of its SSR strategy, the Government seeks to promote equal participation of women and girls as well as greater consideration of their concerns in SSR reform processes. The strategy also notes that women in conflict situations are often prevented from accessing security services. In this context, the Government promises to anchor gender as a cross-cutting issue and to use gender-sensitive analysis instruments. In addition, gender aspects are to be taken into account in the training and further education of German personnel. State security forces of partner countries are to be trained on human rights and SGBV.

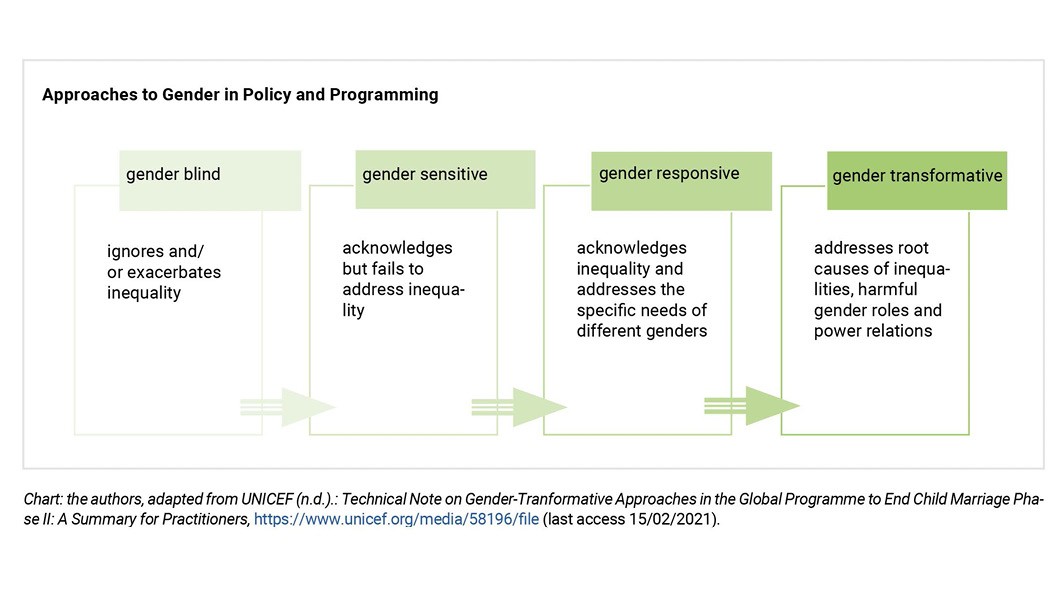

The SSR strategy thus takes up gender issues in several places and can be described as generally gender-responsive. However, it only addresses the specific needs of girls and women, omitting others such as those of LGBTQI+ persons. In addition, the importance of gender stereotypes and roles, for example concepts of masculinity that encourage violence, are not addressed, as they would be in a gender-transformative approach. It also remains unclear how the agreements reached are to be implemented because the SSR strategy does not have explicit target indicators or compulsory monitoring.

Interministerial implementation as a goal

In Germany, SSR support is the responsibility of various ministries that are either involved in international missions or carry out bilateral programs. For example, the Interior and Defence Ministries provide assistance in training and equipment to strengthen the police and armed forces in partner countries. The Foreign Office and the Ministry of Defence jointly carry out training, equipping and advising actors in the security sector in countries such as Iraq, Mali and Nigeria. This initiative is highly controversial given the risks involved in cooperating with fragile states and in some cases authoritarian regimes.

While the SSR strategy is a targeted attempt to strengthen the coherence of German government action, the ministries involved have very different approaches, experiences and priorities in the area of gender. For example, already for some time the Development Ministry has committed itself to a comprehensive, gender-transformative approach to development cooperation. Until recently, this had not been the case for other ministries. However, the National Action Plan (NAP) 1325 (2021-2024), which pursues a gender-transformative approach, has introduced a new level of ambition for all ministries.

The military and police are male-dominated organisations in terms of personnel and culture – not only in partner countries but also in Germany and most EU countries. Not only can this lead to gender-responsive SSR potentially remaining at the lower end of priorities, it also threatens credibility when German actors do promote gender-responsive SSR abroad. It is thus partly understandable that the Defence and Interior Ministries focus primarily on increasing the share of women – in general, but also on foreign assignments – and that gender-responsive work has so far been a niche topic. However, the latter is crucial for a successful implementation of the strategy.

Conflicts in implementation in partner countries

Supporting SSR in partner countries is in itself a sensitive undertaking fraught with many risks for external actors. Often enough it involves strengthening existing elites and security forces which have little interest in carrying out serious reforms and providing security to everyone. Research has shown that SSR support can have long-term success only if the principle of “local ownership” is taken seriously. However, this cannot mean dispensing with the anchoring of gender aspects and thereby reproducing patriarchal structures. State actors who may oppose the inclusion of gender aspects do not necessarily reflect the so-called local context and the needs of different sections of society to an adequate extent. This makes the involvement of various civil society organisations that campaign for gender equality all the more important.

The identification of, and targeted cooperation with, feminist-minded individuals within international missions and state structures is also promising. In addition, the idea of “traditional” partners and “progressive” internationals that often prevails is obviously too simple. Often there are both supporters and skeptics or even opponents of gender-responsive and transformative SSR projects on both sides.

Recommendations for gender-transformative implementation of the SSR strategy

The German Government has set itself highly ambitious goals in its SSR strategy; the new NAP 1325 with its gender-transformative approach has further increased the level of ambition. In order to make implementation transparent and measurable, the government should report on gender-related SSR measures taken within the framework of the NAP 1325, because this has an – albeit soft – monitoring mechanism. Moreover, all ministries should appoint focal points with extensive responsibilities and capacities to implement the agenda. In addition, the German Government should ensure that employees in the SSR sector actually see themselves as responsible for anchoring gender equality as a central principle through targeted personnel recruitment and even more comprehensive training courses.

Crucially, the German Government should ensure that planned reforms and support measures do not define the local context purely and solely in terms of the needs of state actors and that they do not react to possible conflicts with anticipatory obedience. In order to ensure sustainable success of its measures, external actors should at an early stage work together with feminist actors in state institutions and civil society. They know best which measures can realistically be put into place in the respective country.

This blog was originally published in German with the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, available here.

This blog was written with the support of an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant and a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494)

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

Image credit: UN Women (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)