Peace agreements do not represent the totality of a peace process, but they are often critical junctures in transitions from conflict to peace and can shape and set inclusion agendas that endure long after armed conflicts end. Two decades after the UN called on all peace process actors to adopt a gender perspective, but amidst an unpreceded challenge to women’s rights globally under the Covid-19 pandemic, how did peace agreements provide for women, girls and gender in 2020, and what does this tell us about the trajectory of the women, peace and security agenda?

At the Political Settlements Research Programme, we track the frequency and detail of how peace agreements include references to women, girls and gender, and our new update to the PA-X Gender Peace Agreement Database now includes detailed gender coding for all peace agreements from 1990 up to June 2021. This PA-X Version 5 update added 16 new agreements to PA-X Gender,[1] from Central African Republic, Myanmar, South Sudan, and Sudan, agreed between 2011 and 2021, which means that we can now compare gender provisions in peace agreements throughout 2020 to previous years.

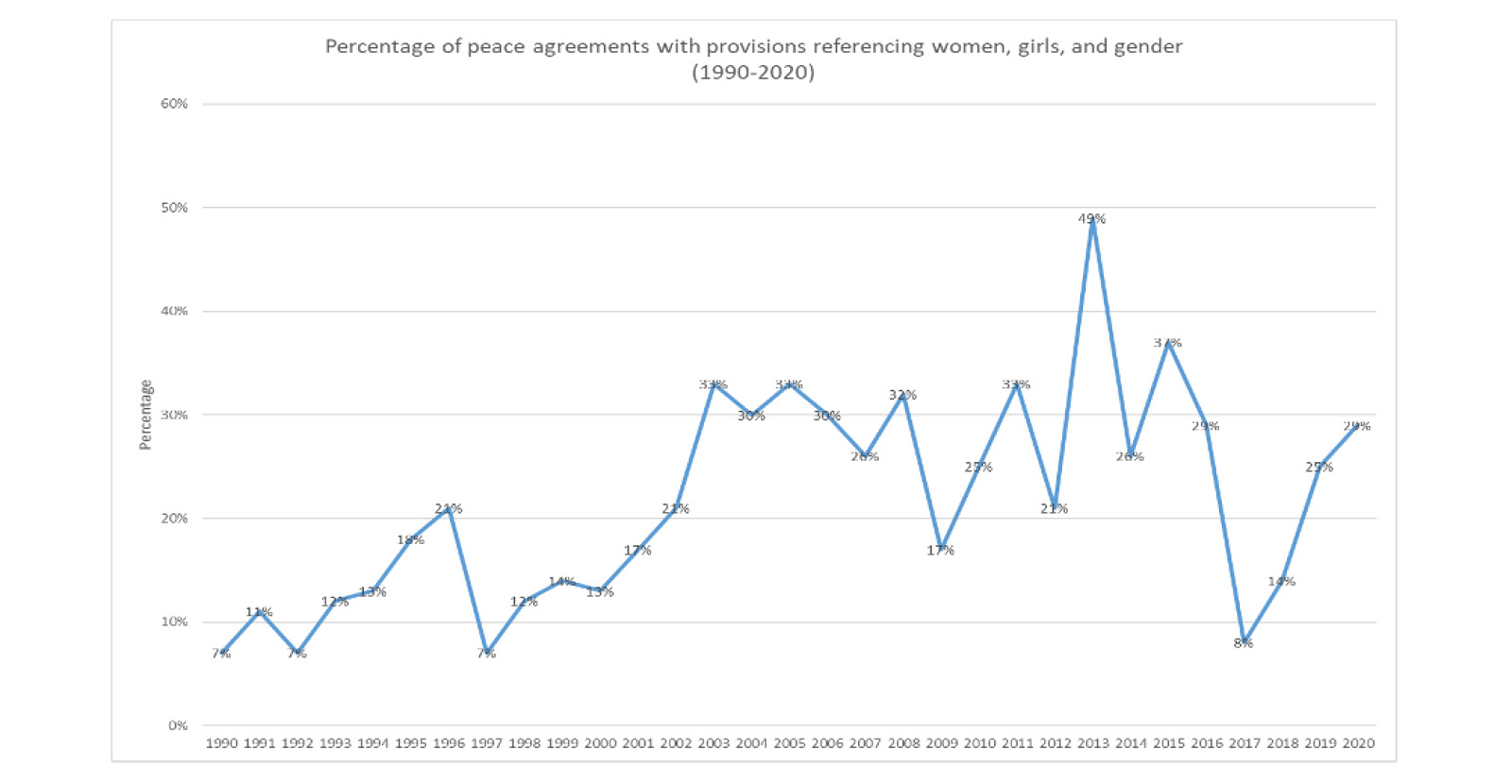

The proportion of peace agreements providing for women, girls and gender in 2020 continued to recover following a drop in 2017, although it remains low. In 2020, 29 per cent of global peace agreements contained references to women, girls, and gender (6 out of 21 peace agreements). This brings the proportion of peace agreements with gender references back in line with a level last reached in 2016 (29 per cent), after this dropped to just 8 per cent of peace agreements in 2017, and continues a positive trend across the 1990-2020 period (Figure 1).

The proportion of peace agreements providing for women, girls and gender in 2020 continued to recover following a drop in 2017, although it remains low.

Figure 1: based on Version 5 of the PA-X Peace Agreements Database

Research suggests that the stage or type of agreement, UN involvement as a third-party, women’s participation and civil society participation in peace processes, conflict duration, and regional distribution can all have an impact on the inclusion of gender references in peace agreements. If we focus on the peace agreement stage, five out of the six peace agreements with gender provisions in 2020 were substantive agreements, which means that they partially or comprehensively address issues core to resolving the conflict, and are therefore more likely to contain references to women than agreements such as ceasefires.

None of the eight ceasefire agreements reached in 2020 refer to women, girls and gender, which is comparable to previous years – only 9 per cent of all ceasefires reached between 1990 and 2020 contained gender provisions, whilst 58 per cent of comprehensive agreements included references to women, girls and gender. As formative stages of peace processes, ceasefires can set the inclusion parameters for subsequent negotiations and this lack of gender references in ceasefires in 2020 shows that more work would need to be done to integrate the WPS agenda into ceasefire negotiations.

five out of the six peace agreements with gender provisions in 2020 were substantive agreements, which means that they partially or comprehensively address issues core to resolving the conflict, and are therefore more likely to contain references to women than agreements such as ceasefires.

Only three peace agreements in 2020 included provisions relating to violence against women

Turning to the substance of gender references in peace agreements, PA-X Gender codes the content of each text for the following categories about women, girls and gender: participation; equality; particular groups of women; international law; new institutions; violence against women and gender-based violence; transitional justice; institutional reform; development; implementation; and other references to women. In 2020, provisions addressing violence against women and development were the most prominent categories (included in three agreements), whilst provisions for international law and women’s roles in implementation only appeared once each across all six agreements.

However, simply counting provisions overlooks the fact that peace agreements vary in the detail and strength of conflict parties’ written commitments. The 2020 ‘Reconciliation pact between the North-Eastern communities’ in CAR simply includes rhetorical commitment “to end violence and cruel treatment against women”, but with no substantive detail about how parties will do this. The ‘New Decade, New Approach’ deal in Northern Ireland is more substantive, as it includes provisions relating to a report on “the handling of serious sexual offences cases”, and a redress scheme for “survivors and victims of historic abuse”.

The ‘Juba Agreement’ in Sudan contained the most substantive references to violence against women, sexual violence, and gender-based violence, and was also the most comprehensive agreement for gender provisions across all issue categories in 2020. The agreement includes provisions that designate violence against women as a prohibited act, recognise male and female survivors of rape as “victims of the conflict in Darfur”, and aim to protect internally displaced and refugee women from “all forms of harassment, exploitation, and sexual- or gender-based violence”.

Overall, the inclusion of more substantive provisions to address violence against women and gender-based violence in the Juba agreement stands out as an isolated achievement, particularly as the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated root causes and drivers of sexual violence and made it even harder for women and girls in conflict settings to access support and protection.

If only 14 per cent of agreements reached globally in 2020 mentioned violence against women, despite the ongoing widespread use of sexual and gender-based violence in conflict, then there is a long way to go before peace agreements generally adopt the approach advocated by UNSCR 2467 (2019), which calls for “ceasefire and peace agreements [to] contain provisions that stipulate sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations as a prohibited act”.

Only two peace agreements in 2020 listed signatories of women’s networks, but this is comparable to previous years

The WPS agenda calls for women to participate meaningfully in all facets of peace processes, including formal Track 1 negotiations, where traditionally women have been underrepresented. Research from the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) on women’s participation in peace processes suggests that “between 1992 and 2019, women constituted, on average, 13 percent of negotiators, 6 percent of mediators, and 6 percent of signatories in major peace processes around the world.” Whilst the PA-X Database does not code for individual women as signatories, and cannot directly compare to the CFR data for 2020, we do code for women signing as part of a specific women’s group, or women’s delegation.

Only two peace agreement in 2020 included any references to signatories on behalf of women and none of the agreements provided for women being given a specific role in implementing the agreement. The ‘Reconciliation pact between the North-Eastern communities’ in CAR listed two signatories representing women from different communities: Rosalie Blitchli representing women from Hautte-Koto and Fatimé Senoussi representing women from Bamingui-Bangoran.

In South Sudan, Mary Yar signed the ‘Pageri Peace Forum Resolutions’ on behalf of the Women Association Network Nimule, although the document also states that 19 out of the Forum’s 75 participants were women. However, this is comparable to previous years: only two peace agreements in 2019 had signatories on behalf of women’s groups or networks, and between 1990 and 2019, only 1 per cent of agreements were signed by someone representing a specific women’s group, women’s delegation, or as representing women.

This is not to overlook prominent women who held key roles in Track I peace processes in 2020. In Myanmar, Ja Nan Lahtaw and Chin Chin were two out of the three co-facilitators of the political dialogue between the Government and Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs), and the Union Accord Part III was signed by Dr May Win Myint, Daw Khin Ma Ma Myo, and Nang Aye Aye Thwe, on behalf of the Hluttaw, the Ethnic Armed Organisations, and the Political Parties Group, respectively. The permanent ceasefire agreement reached in Libya was brokered and signed as a witness by Ms Stephanie Williams, as the Acting Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General and Head of UNSMIL.

Despite these representational gains, however, the small number of signatories on behalf of women’s groups suggests that the overall proportion of women formally participating in peace processes is still far too low to match the ambitions set by the WPS agenda, and does not reflect the widespread and active mobilisation of women peacemakers in conflict-affected contexts.

2020 was a year that brought unprecedented challenges, for both gender equality advocates and those bringing conflict parties to the peace table. In a time of such dramatic change, peace agreement references to women, girls and gender did not reflect the global disruption to the status quo when compared to previous years and particularly in the post-UNSCR 1325 period. Perhaps sustained levels of inclusion, both of gender provisions and women as peace agreement signatories, in states and politics of emergency where conflict parties had many opportunities and excuses for excluding women from negotiations, is no small achievement for the WPS agenda.

Despite these representational gains, however, the small number of signatories on behalf of women’s groups suggests that the overall proportion of women formally participating in peace processes is still far too low

Every meaningful reference to women in a peace agreement is the result of decades of work by gender equality advocates and activists, and the fact that the 2020 Juba agreement calls for 40 per cent effective representation of women at all levels of power and decision-making, is an example of this progress. However, 20 years from UNSCR 1325, peace agreements are still a long way from adopting a gender-sensitive perspective, and women remain underrepresented at negotiation tables. As the Covid-19 pandemic accelerates in many parts of the world and progress in peace processes ebbs and flows, women peacemakers persist across conflicts, yet it remains to be seen whether this inclusion stasis continues as we move forward.

[1] PA-X Version 5 added 47 new agreements spanning dates from 2008 – June 2021, 14 of which include provisions referencing women, girls, and gender. However, this update to PA-X Gender also includes two agreements from prior PA-X data releases, which have now been reclassified as including gender references (Agreement ID 1580 and ID 2197).

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

Image credit: MONUSCO Photos (CC BY-SA 4.0)

1 Comments