As ardent Eurosceptics and ‘Anglosphere enthusiasts’ David Davis, Boris Johnson and Liam Fox take leading roles in shaping Britain’s place outside of the EU, we might expect the ‘Anglosphere’ to become increasingly prominent in British political discourse in coming months and years. Helen Baxendale and Ben Wellings foresee deeper and broader bilateral relations between English-speaking countries, yet judge that a formal Anglosphere alliance may yet remain a ‘work of political science fiction’ – even though it is no longer an obscure one.

As ardent Eurosceptics and ‘Anglosphere enthusiasts’ David Davis, Boris Johnson and Liam Fox take leading roles in shaping Britain’s place outside of the EU, we might expect the ‘Anglosphere’ to become increasingly prominent in British political discourse in coming months and years. Helen Baxendale and Ben Wellings foresee deeper and broader bilateral relations between English-speaking countries, yet judge that a formal Anglosphere alliance may yet remain a ‘work of political science fiction’ – even though it is no longer an obscure one.

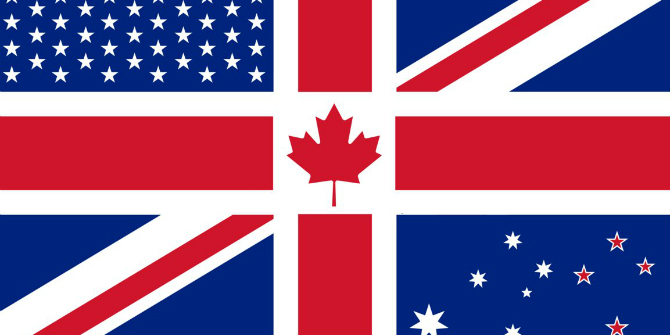

In 2005, the late historian of the Soviet Union, Robert Conquest, optimistically argued that ‘after the EU monster has lumbered off or been corralled’ a formal Anglosphere Alliance, should emerge as a new centre of power and standard bearer of Western values. The idea is that Britain, the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand should cooperate even further in trade, diplomacy and security because it makes more cultural and historical sense than the alternatives. A decade ago, Conquest believed the notion would very likely remain a work of ‘cultural and political science fiction.’ Yet, in the wake of a referendum result that surprised most pundits, and apparently senior Brexiteers themselves, Britain is once again looking to the ‘open sea’ rather than the Continent. The Anglosphere idea offers an ‘off the rack,’ model of international engagement that is inherently appealing to many on the right of British politics.

The Anglosphere idea in the EU Referendum

In February 2016, David Davis delivered the most explicit invocation of the Anglosphere idea of the Referendum campaign:

We must see Brexit as a great opportunity to…renew our strong relationships with Commonwealth and Anglosphere countries. These parts of the world are growing faster than Europe. We share history, culture and language. We have family ties. We even share similar legal systems. The usual barriers to trade are largely absent…it is time we unshackled ourselves, and began to focus policy on trading with the wider world, rather than just within Europe.

In addition to liberal trade arrangements, fellow Brexiteer, Michael Gove, extolled the openness, innovation, and democratic traditions of other Anglophone nations. All of these attributes, he argued, would become more pronounced in Britain following a ‘declaration of independence’ from what he portrayed as the stifling, sclerotic EU. Gove’s intervention illustrated the way that for Brexiteers Anglosphere countries operated as models carrying a legitimacy that didn’t need explanation or elaboration in the way that aligning England and the United Kingdom with European countries did.

The ‘Australian-style points-based immigration system’ was one such example: ‘My ambition is not a Utopian ideal – it’s an Australian reality’ Gove told an audience of Vote Leave supporters in April 2016:

Instead of a European open-door migration policy we could… emulate that country’s admirable record of taking in genuine refugees, giving a welcome to hard-working new citizens and building a successful multi-racial society without giving into people-smugglers, illegal migration or subversion of our borders.

Brexiteers also seized on Canada as an instructive model for the way that a post-EU UK might underpin its new economic relationships with the EU and the wider world. Norman Lamont, suggested that the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) (or “Canada+”) would be a good model for the UK after a Brexit.

Significantly, however, there was major pushback to a new Anglophone order from within the very countries that were supposed to form the basis of Britain’s post-EU paradigm. Speaking in Munich in February 2016, US Secretary of State, John Kerry, reminded his audience that: ‘the United States has a profound interest in your success as we do in a very strong United Kingdom staying in a strong EU.’ Leaders of the other three Anglosphere states reinforced this view. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau argued that ‘we’re always better when we work as closely as possible together, and separatism or division just doesn’t seem to be a productive path for countries.’ From a more instrumental point of view, New Zealand Prime Minister John Key observed that: ‘If we had the equivalent of Europe on our doorstep… we certainly wouldn’t be looking to leave it.’

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull echoed this international consensus, repeating in May 2016 the Australian government’s position that: ‘We welcome Britain’s strong role in Europe…having a country to whom we have close ties and such strong relationships… is definitely an advantage.’ The former Australian Foreign Minister, Gareth Evans penned a piece in The Australian lampooning the ‘bizarre argument’ ‘that a self-exiled UK will find a new global relevance, and indeed leadership role, as the centre of the Anglosphere.’ Even the ‘incorrigible Anglophile’ Tony Abbott was outwardly cold on Brexit. In a lead article for The Times, the former Australian Prime Minister urged that ‘Britain must stay and save Europe, not abandon it.’ An erstwhile proponent of ‘Anglospherism’ Niall Ferguson, shared this view, likening Brexit to an ill-tempered and expensive divorce, that would inevitably result in ‘Breturn’ to save an ailing Europe. Only John Howard, broke with the elite international consensus, denouncing the EU as ‘an affront to the sovereignty of its member countries.’ The opinions of international leaders were seized upon by Remain campaigners who argued that Britain would find itself isolated outside of the EU in a hostile world (a re-run of an argument from 1975).

After the Referendum: The Anglosphere and Britain’s new role

Though the Referendum result may presage a major geopolitical shift, the notion of a formalised Anglosphere Alliance remains unlikely, though it is not as far-fetched as it seemed a few months ago. Certainly, Anglosphere proponents greeted the Brexit vote with unbridled delight. Prominent American conservative, Roger Kimball, remarked that ‘had Britain voted to remain in the EU, the Anglosphere would have continued, but Britain would have lost its prominent role in it as it slipped more and more into the adipose embrace of the central planners in Brussels.’

Indeed, May’s new Cabinet looks like something of an ‘Anglosphere dream team.’ Quite what this means for Britain’s Anglophone allies is still unclear, but the Foreign Secretary’s earlier musings about a bilateral Free Labour Mobility Zone between Britain and Australia are indicative. Prime Minister May has also wasted no time in instigating preliminary discussions over free trade agreements with the United States and Australia.

While Brexiteers are already heralding this news as evidence that the UK will thrive outside of the EU, challenges remain. There is a clear and perhaps irreconcilable tension between the liberal free traders that led the Brexit campaign and those who voted for Brexit in reaction to the effects of the economic and cultural globalisation that EU policies helped promote. Perhaps the Brexiteer free-traders imagine things will be different for these ‘losers of globalisation’ under an Anglosphere trade bloc rather than a European one?

A second profound challenge is the status of the Union itself. In her first press conference as Prime Minister, Theresa May was at pains to stress the ‘precious bond between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.’ One imagines that any formalisation of deeper Anglosphere ties will be secondary to the pressing need to clarify England’s relationships with the other home nations.

Conclusion

Brexit has propelled ‘the Anglosphere idea’ up the foreign policy agenda in the United Kingdom and beyond. Indeed, deeper and broader bilateral relations between English-speaking countries are highly likely. A formal Anglosphere alliance may yet remain a ‘work of political science fiction’ but it is no longer an obscure one. The promotion of Anglosphere enthusiasts to key posts in Theresa May’s cabinet and the response from Anglophone powers such as Australia suggest that it is an idea coming in from the cold.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of BrexitVote, nor of the London School of Economics. Image credit.

Helen Baxendale is a Doctoral candidate in Public Policy at the University of Oxford, supported by a Rhodes Scholarship.

Ben Wellings is Lecturer in European Studies at Monash University. He is the author of English Nationalism and Euroscepticism: losing the peace (Peter Lang, 2012).

1 Comments