The frenzied negotiations to conclude the first phase of Brexit negotiations have usefully clarified the real choices faced by the British government in the second phase. The ambiguous and variously defined terms “soft” and “hard” Brexit have outlived their usefulness. As it turns out, Brexit is a blank sheet of paper that can never be filled in, writes Brendan Donnelly (Federal Trust).

The frenzied negotiations to conclude the first phase of Brexit negotiations have usefully clarified the real choices faced by the British government in the second phase. The ambiguous and variously defined terms “soft” and “hard” Brexit have outlived their usefulness. As it turns out, Brexit is a blank sheet of paper that can never be filled in, writes Brendan Donnelly (Federal Trust).

It is clear that the British government must now decide whether it wishes after Brexit to remain close to the standards and regulations of the European Union, thereby limiting the economic damage and disruption from a radical break with the Union. Or whether, on the contrary, it wishes for political reasons to facilitate this radical break, even to the extent of leaving the Union with no agreed template for future economic relations between the two sides. The vigorous debate at the beginning of December about a possible “hard” or “soft” border within the island of Ireland arose largely from the fact that the British government has not yet decided which of these two options it favours. The confused nature of the text relating to Ireland finally adopted by the EU and UK reflects this continuing uncertainty.

The Conservative government is now coming to realize that if it wishes to bring about any kind of Brexit it will be forced to make painful choices

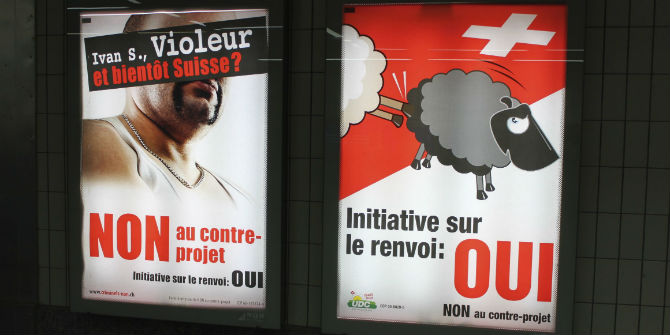

Those who voted for Brexit in June 2016 were always divided between those wanting a radical break with the EU and those wanting to maintain the status quo as far as possible. This division was to some extent concealed by the reassuring but unrealistic argument of the “leave” campaigners that if it left the EU, the United Kingdom would be able to dictate whatever terms for it wished for its future relationship with the Union. This disingenuous argument not merely tapped into British delusions of grandeur, it was also an important instrument for keeping together the disparate wings of the “leave” campaign. The Conservative government is now coming to realise that if it wishes to bring about any kind of Brexit it will be forced to make painful choices. The EU has made plain that it sees these painful choices as a necessity the UK has inflicted upon itself. Any help the UK can expect from its former partners in lessening the pain will, therefore, be limited. The Union itself has important interests to defend in the Brexit negotiations, some of which run counter to short-term British interests. The Union can and will defend those against an obviously weaker negotiating partner.

A peculiar difficulty for the divided Conservative Party is posed by the fact that both its contrasting wings have apparently unanswerable objections to each other’s position. Those favouring a less radical breakpoint to the near-unanimous agreement of business, the City and economic analysts that an abrupt and wide-ranging disengagement from the Union will increase substantially the economic damage wrought by Brexit. It was pressure from such sources, many of them traditionally Conservative-leaning, that led to Theresa May’s capitulation to the EU’s terms for concluding the first phase of the Brexit negotiations. The radicals in her party point on the other hand to the political incoherence of a decision to leave the EU and yet to continue to be substantially bound by its regulatory decisions, decisions the UK will have had little opportunity to influence. The vote to leave the EU, argue the radicals, was one to “take back control” and this vote demands the greatest possible level of emancipation from EU intrusiveness. Within the Conservative Parliamentary Party, opinion tilts towards those favouring a less abrupt and dislocating Brexit. Within the Conservative Party as a whole, there is a clear majority for a more radical and disruptive approach.

Canada plus or Norway light

Almost certainly, the British government will attempt in the first stages of the second phase Brexit negotiations to put forward some kind of a “bespoke” arrangement for future economic relations between the UK and EU – it is this prospect which May has used to try and maintain unity in her fractious party. David Davis seems to have had something similar in mind in his reference to “Canada plus plus plus,” or a trade arrangement more favourable to the UK than that enjoyed by Canada, but with little or nothing in the way of extra obligations on the UK compared with Canada’s. It can confidently be predicted that this proposal will make little headway. When Michel Barnier speaks so dismissively of British attempts to “cherry pick” in the Brexit negotiations, he is faithfully reflecting the views of the European Council and of France and Germany in particular. For the Council, it is now up to the UK to opt either for the arm’s length trading relationship implicit in the model of its arrangement with Canada, or to seek a more intimate economic relationship, comparable to that between the EU and Norway, a status which can only be accorded on the basis of acceptance by the UK of corresponding obligations. The European Council called indeed in this month’s conclusions for the UK now to clarify its choice between these options in a way that it has failed to do until now.

If and when this clarification occurs, it will have interesting implications for the Brexit process more generally, particularly in the House of Commons. The Labour Party has made increasingly clear in recent months that it will not accept a radical, disruptive Brexit. The logic of this position, even if Labour has been reluctant to articulate this publicly, is that the UK should remain in the EU Customs Union and in the single market. May on the other hand is committed to taking the UK out of both, hoping forlornly that it will be possible to agree equivalent arrangements after Brexit for “frictionless” trade with the EU. The likely unwillingness of the EU to concede any such “bespoke” agreement will set the scene for domestic UK political confrontation in the summer or autumn of next year. The Conservative Party can corporately never accept anything comparable to the status of Norway vis-à-vis the EU. There can never be, however, a majority in the Commons for taking Canada as a model of the UK’s economic relationship with the EU. David Davis is seeking to disguise this latter reality with his fanciful talk of “Canada plus plus plus,” a bespoke arrangement by any other name.

Commentators have rightly been cautious in assigning significance to the rebellion of 11 Conservative MPs’ seeking to achieve a “meaningful” vote on Brexit for the Commons next year. The rebellion itself was narrowly focussed and its authors disavowed any general attempt to undermine the government’s Brexit policy. It is, however, worth recalling that the Eurosceptic revolts of the 1990s were equally limited in their beginnings and were carried out by MPs claiming to support the general European policy of the Conservative government. The rebellion does suggest that there are those within the Conservative Parliamentary Party willing to take a stand against the hitherto unchallenged radical Eurosceptic drift of governmental policy on Brexit. If, as seems likely, May fails to negotiate a “bespoke” Brexit agreement and is forced to return to MPs with an arrangement very similar to that negotiated by Canada, there is a good chance that there will be Conservative MPs prepared to contest that outcome and join with the Labour Party in doing so. It would not take many MPs to join this contestation for May’s majority to disappear.

No agreed template for Brexit

When New Labour attempted to reform the House of Lords, one of the major procedural difficulties it faced was the inability of reformers to agree on the nature of the new second chamber they sought, an inability gleefully exploited by those hostile to any reform. It is entirely possible that something similar may be the fate of Brexit, with no individual model for the UK’s withdrawal from the Union being able to command a majority of MPs. The former diplomatic adviser to Margaret Thatcher, Lord Powell, was recently quoted as saying that the divisions in the Conservative Party over Europe were so deep that the party was “more or less bound to split at some point.” The choice between the Canadian model and the Norwegian model after Brexit may well occasion this split. If so, all previous calculations about the inevitability of Brexit will need to be reassessed. The unity of the Conservative Party has been a powerful instrument in the hands of the Eurosceptic minority of Conservative MPs as they sought over the past twenty years to bend the party, usually successfully, to their radical and populist agenda. The loss of that unity of itself would render the realisation of Brexit considerably more difficult to bring about successfully.

It is a favoured argument of many on the radical Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party that if the Commons attempts to reject the agreement reached by May in the autumn of next year, that rejection will be null and void and the UK will anyway leave the EU in March 2019 in accordance with the terms of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. This argument would be correct only if MPs, having rejected May’s proposed text, were content simply to remain inactive and impotent until March 2019. There is no reason to assume that such would be the case if the Commons had once steeled itself to take the far-reaching step of disavowing the results of May’s negotiations. A number of options would be open to the Commons in those circumstances, not least that of a new referendum for the voters to choose between accepting the result of the government’s Brexit negotiations or remaining in the EU. Public opinion has recently been shifting significantly in favour of such a second referendum, influenced no doubt by the realisation of the lies and wishful thinking that underpinned so much of the “leave” campaign.

In 2002, Davis remarked that referendums should only be held if voters were told “exactly what they were voting for.” In particular, the electorate should not be asked to vote on a “blank sheet of paper.” The 2016 EU referendum could not by any stretch of the imagination be held to meet this threshold. It would be a delicious irony if Davis had the opportunity forced upon him in late 2018 to prove his intellectual consistency by accepting the need for another European referendum, with its consequences more exactly specified than was possible in 2017. The arguments in favour of such a referendum would not require from the Brexit Secretary much intelligence or factual knowledge to be understood. They would therefore fall squarely within his self-proclaimed capacities. The referendum itself may on the other hand test the calmness to which he has recently laid claim. It will not be as easy to sell the electorate a distinctly mangy Brexit pup the second time around as it was the first time.

An earlier version of this post appeared on The Federal Trust and it represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Brendan Donnelly has been Director of the Federal Trust since January 2003 and is a Senior Research Fellow at the Global Policy Institute. He is a former Member of the European Parliament (1994 to 1999).

A typically perceptive analysis from Brendan Donnelly. Two points to add –

1. There must be a.great danger of the way forward remaining obscure until it is too late for the Lib Dem -style “referendum on the destination” to take place. The EU have made it clear that the initial objective will be to finalise details of the exit and agree arrangements for a transition period. They have said it will only be possible to draw up “a political declaration on the future framework for trade” by the brexit date in February 2019 let alone the much earlier date required to permit a new referendum. Moreover the longer the Labour Party retains its tactical position of merely saying ” it will not accept a radical, disruptive Brexit” the more uncertainty of the balance of opinion in the Commons will persist.

2, The Irish situation can still have a crucial part to play. The words in the Phase 1 agreement (which will shortly be drawn up in legally defined terms despite the clumsy attempt by David Davis to decry their conclusiveness) are to my mind definitive – ” the United Kingdom will propose specific solutions to address the unique circumstances of the island of Ireland. In the absence of agreed solutions, the United Kingdom [i.e. the entire United Kingdom] will maintain full alignment with those rules of the Internal Market and the Customs Union which, now or in the future, support North-South cooperation, the all island economy and the protection of the 1998 Agreement.” The extent of joint arrangements across the Irish border means that “rules of the Internal Market and the Customs Union which, now or in the future, support North-South cooperation, the all island economy and the protection of the 1998 Agreement.” are bound to be quite a chunk of the totality of such rules.

Does this not mean that the UK is already committed to a large measure of alignment with the standards and regulations of the European Union?

I see the force of both the above points. There is a good article by Nick Clegg in today’s FT about the options for Parliament later this year. I suspect that if Parliament rejected the results of the Government’s Brexit negotiations the U.K. would need and get a new government which could then look afresh at the whole question of Brexit. As to the Irish border I agree that logically the U.K. should be logically committed by last month’s Phase 1 agreement to remaining in most of the Customs Union and most of the Single Market. Logic is however not always a reliable guide to the future twists and turns of the Brexit saga.