The Scottish Parliament has denied consent to the EU Withdrawal Bill. In this blog, Akash Paun (Institute for Government) argues that the Prime Minister now faces an unpalatable choice: concede defeat or help the SNP make the case for indyref2.

The Scottish Parliament has denied consent to the EU Withdrawal Bill. In this blog, Akash Paun (Institute for Government) argues that the Prime Minister now faces an unpalatable choice: concede defeat or help the SNP make the case for indyref2.

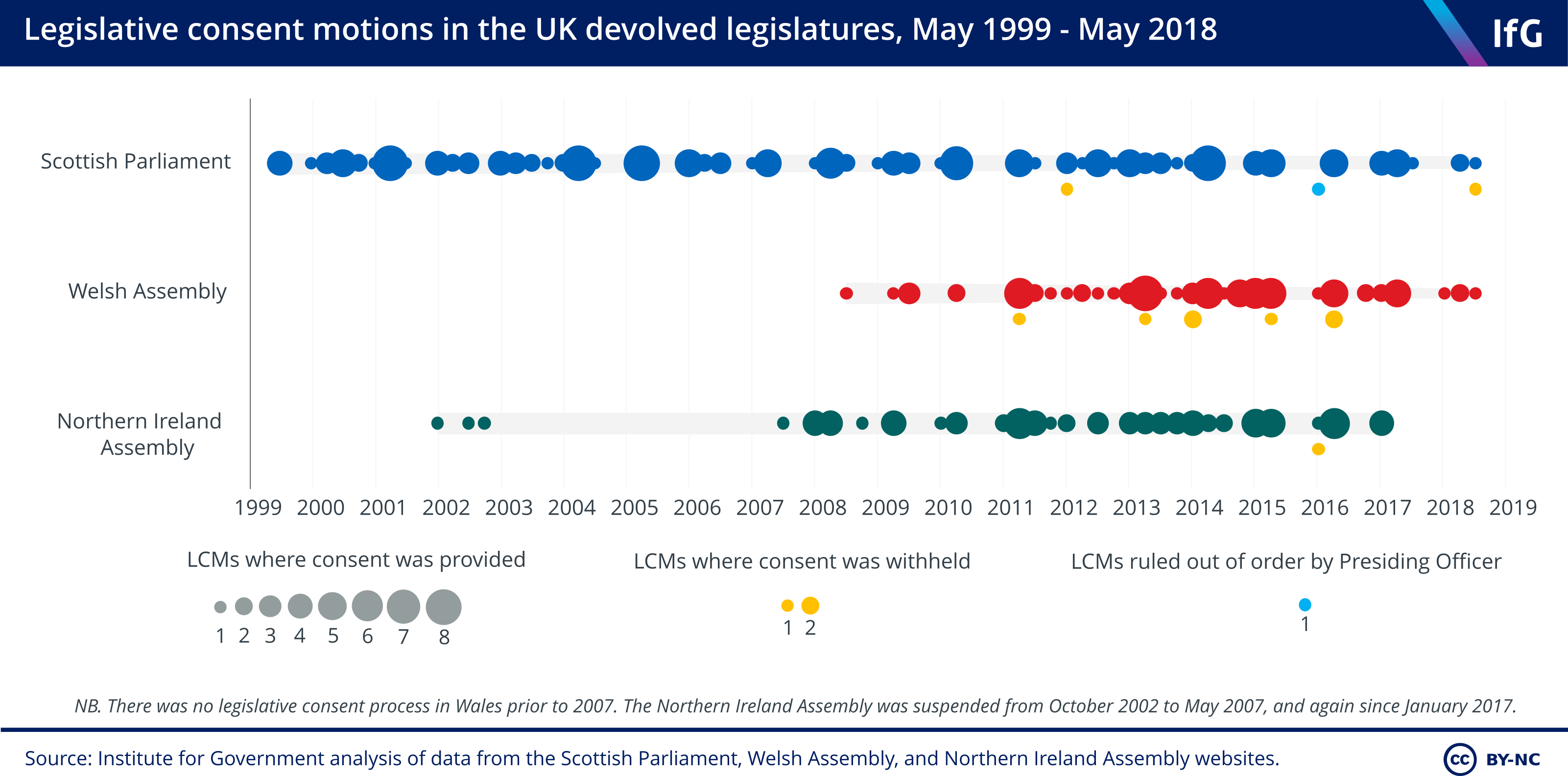

And lo it came to pass. After nearly two years of wrangling over the impact of Brexit on devolution, the Scottish Parliament has voted by 93 to 30 to withhold “legislative consent” for the EU Withdrawal Bill. The bill amends the powers of the Scottish Parliament and Government and should therefore “not normally” be passed without devolved agreement (under the Sewel Convention). This is a major constitutional moment – since 1999 MSPs have granted consent to Westminster legislation 171 times. Just once have they said no. On that occasion, relating to the 2011 Welfare Reform Bill, the British Government amended its plans, following which the Scottish Parliament reconsidered the matter and granted consent to the revised legislation.

The current impasse could yet be overcome in a similar way. The House of Lords will tomorrow send the bill back to the Commons, so MPs still have time to amend the bill further if agreement is reached between the two governments. But that is a big if. The British Government has made significant concessions already, sufficient to gain the consent of the Welsh Assembly. But in the case of Scotland, the two sides remain at odds on a fundamental point of principle.

The UK Government position is that Westminster needs the power to impose (temporary) restrictions on devolved power in certain areas governed by EU law, such as agriculture, fisheries, food standards and animal welfare. This, it says, is necessary to ensure legal certainty until the UK decides what to put in place of EU frameworks. The Scottish Government considers this an unwarranted incursion into Scotland’s autonomy.

Speaking yesterday in London, Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister made plain that this is a red line that no ‘self-respecting First Minister of the Scottish Parliament’ could be expected to cross. Her counter-proposals are that the offending clause of the Withdrawal Bill be dropped altogether, or that any constraints on devolution are imposed only with the express agreement of Holyrood. In other words, there should be a legal veto power, applicable on a case by case basis, not simply a convention of seeking agreement.

The SNP position is strengthened by the support it received in today’s vote from the Scottish Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green parties. Only the Scottish Conservatives voted to back the Withdrawal Bill. In this context, might the Prime Minister simply cut her losses and drop the offending provisions?

This must be tempting – the Government’s Brexit strategy is in danger of falling apart, and conceding on the devolution question would at least bring peace on one front. But Whitehall holds genuine concerns about the economic implications of Scotland creating its own regulatory framework immediately after exit day. So the Government might resolve to push through its legislation without consent, for the first time in the history of devolution.

The Prime Minister will meanwhile also hope that the Supreme Court strikes down Scotland’s rival EU Continuity Bill, which UK ministers believe may fall outside of Scotland’s devolved competence. The risk for the Prime Minister is that to legislate without consent would make the SNP’s argument for it. Nicola Sturgeon yesterday asserted that if Westminster were to “carry on regardless” this would “demonstrate that we were right” not to “take on trust” that UK ministers would not misuse the powers in the Withdrawal Bill to rewrite the law in devolved areas.

That in turn will be used to bolster the case for a second independence referendum, which for the SNP remains a matter of “when” not “if”. Sturgeon will outline her approach on the next steps towards this goal in the autumn. Prior to that, her party will set out its thinking on crucial economic questions such as what currency an independent Scotland would adopt.

Image by Alf Melin, (Flickr), (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Image by Alf Melin, (Flickr), (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Nicola Sturgeon last pressed the #indyref2 button in a speech in March 2017, but Theresa May rejected the demand for a second vote on the grounds that “now is not the time”. The SNP’s poor election performance in June 2017 pushed the issue further onto the backburner. But as the contours of the future UK-EU relationship emerge slowly from the fog over the coming months, the First Minister will be able to argue more persuasively that the time has now arrived.

It would be a gamble, no doubt. The polls do not indicate a pro-independence surge, but after the shock of 2016 only a fool would predict the outcome with confidence. Westminster could in principle refuse to allow another referendum, but emulating Madrid’s handling of Catalonia would surely not be the right course of action. Westminster conceded in 2014 (if not 1999) that Scotland has the right to self-determination, just as the Good Friday Agreement allows for Irish reunification with sufficient support in both parts of Ireland. These constitutional genies cannot be put back into the bottle.

The Prime Minister, therefore, faces a choice. Concede defeat on the Withdrawal Bill, at the expense of losing some control over post-Brexit regulatory arrangements. Or hold course on Brexit, and prepare for a bigger battle over the future of the British Union.

This post represents the views of the authors, and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It first appeared on the Institute for Government blog.

Akash Paun is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Government. Akash has worked at the Institute since 2008, having previously worked as a researcher at the Constitution Unit, UCL. He has a broad interest in constitutional change and the comparative study of political systems.

scotland had a referendum on independance already.

they voted to stay part of the uk.

sturgeon is actually trying to overturn the scottish referendum outcome, and also the uk one.

-if scotland decides to leave the uk- they can , have a referendum and leave the U.K.

-with the green light from 27 other E.U countrys- join the E.U.

as you may have noticed the other EU countrys are not partial to parts of their countries ( catalogne, brittany, corsica to name 4 off the bat) seeking independance.

They would veto any breakaway areas as not to set a precedant.

– their currancy MUST be the EURO- no if’s- no but’s- and to be subect to their laws and governance being overidden by E.U laws.

it is quite simple, no need to waffle on with graphs and flow charts.

Scotland is NOT part of another country, it is a kingdom in union with another kingdom.

Actually, so much of your post is wrong that it seems obvious that you know very little about Scotland or its politics.

Please apologise for your lack of knowledge of Scottish politics. The article writer is correct that T May cannot win against a government which has a mandate for a referendum on Independence.

Are we an independent country? No, so therefore the FM is not ‘overturning’ any result. But wait! You think Scotland is an ‘area’? That is where your whole argument falls down.

There is so much ignorance, bigotry and poor educational standards revealed by ‘toecutter’ I don’t know where to begin.

Firstly, these are the correct spellings of the following words from the post:

independence (not ‘independance’)

Catalonia (not ‘catalogne’)

precedent (not ‘precedant’)

currency (not ‘currancy’)

countries (not ‘countrys’)

ifs and buts (no apostrophes)

Secondly, Nicola Sturgeon is not ‘trying to overturn’ any referendum results, except in your misguided and angry imagination.

Thirdly, Scotland is not an ‘area’ trying to ‘break away’ but a country in a Treaty of Union with England and it has the legal right to dissolve the Union.

I suggest you go away and improve your level of education and knowledge before spewing your nonsense on a public internet forum produced by a university. Perhaps the Sun or the Daily Mail would be more at your level.

The 2014 was won on pledges, vows , promise , threats and the big one that makes that vote void. Guarantee ! The only way to guarantee membership of the EU for the Scots was to vote NO. Many did on that and the various pledges , vows and pledges.

The definition of a Guarantee- An assurance based on principle and honour that the product or service offered will be met. Should it fail to meet that criteria then the contract is void.

After the NO vote the Unionists not seeing another independence betrayed so many. 2000 HRMC jobs, 1 billion carbon capture scheme, Investment in renewables, 13 frigate order and many more. What a shameful betrayal and litany of lies that insults so many people that voted to stay in the Union in good faith.

Dear oh dear toecutter, it’s difficult to understand how someone could comment on Scottish politics & know so little about the subject. Some friendly advice….do some basic research before commenting on a subject you are clearly ignorant of.

Scotland is a country not a region of England or the UK. No need to take the Euro either..

Not only that, we cannot adopt the Euro. To do so a country must have its independent currency exist stably in ERM II for at least 2 years prior to accession. Stirling is famously not in ERM II so cannot use Sterling to do it. Our Scotpound could not be expected to be stable for some time after we float it, it is expected to be needing to be pegged for some time before that in order for a foreign currency fighting fund to protect it from the Soros’s of the world when we do float it.

So, even should we wish to join the Euro, it would be quite some years in the future. Beyond 2030 would be my guess. And why we would want to give up the benefits of a sovereign fiat currency so soon is beyond me.

A well written article and more realistic than the comments of “toecutter”.

Toecutter should realise that the SNP manifesto specifically indicated an intention to hold another referendum if the result of the Brexit referendum turned out as it did. The Scottish Parliament has endorsed the holding of such a referendum if Sturgeon wishes to call it. Opposition by unionists to it is likely to be counterproductive especially as it is obvious that the main reason that May opposes it is fear of defeat.

In giving up EU membership UK has lost the support of that club, something which Spain has not done and therefore Spain (incorrectly in my view, but that is another issue) is supported by the EU on Catalonia.

The contrasting attitude of Guy Verhofstadt (European Parliament’s representative on Brexit) is highly informative-he has expressed the view that Scotland would readily be admitted to the EU whereas he is profoundly opposed to Catalonia splitting from Spain (I do not agree with this rejection of Catalonia, but it is the position).

As to the obligation to join the Euro-Sweden gives the lie to such an obligation.

The Westminster power grab does not bolster the case for a second independence referendum it bolsters the case for independence.

There will be a second referendum as circumstances have changed radically. The Scottish Government has a mandate for a second referendum because of Brexit and it has been supported in vote by the Scottish parliament.

Scotland does not need to join the Euro. To qualify we need to join the ‘Exchange Rate Mechanism II’ for two years, and sign up to that is voluntary. Most likely Scotland will have its own currency.

toecutter, I am Scottish. I decide the future direction of my country, not you.

All this nonsense will be exposed as such during the upcoming Independence plebiscite. We voted Remain, and Remain we shall.

Get off your exceptionalist arse and start thinking of the untold damage the alt Right English Establishment is going to visit upon No Deal Brexit England.

In April 2019 you will be munching on chlorine bleachedKentucky chicken and steroid bloated Texas T Bone steaks.

Scotland has a ready market for our Aberdeen angus beef and Ayrshire Free Range chickens.

500 million customers in 27 countries.

I wish you luck as you are subsumed into Donald Trump’s US of A as the 51st state.

The Marriage of the two ‘Royal’ houses, the Windsors and USA Soap Opera Royalty will cement the Partnership.

Good luck; you’re going to need it.

btw you are free to join us up here. We have plenty of room.

You can have your nuclear subs back too.

Much like BREXIT, I no longer really care.

Go, stay, as you will, but be aware that there is an anti-SNP backlash growing in England that would likes vote too on whether you stay or go…

Children, children!

I think the heat generated in these discussions (which seems to me excessive) is because they are really about questions of identity. Thus I suppose most of the SNP would identify first as Scottish, then as European and with the UK a distant last. I would identify as UK first, then English, and then European (not so distantly). These identifications are of course quite irrational, which is probably why people get so upset about them.

It’s not really about economics, though we pretend that it is. I would be very upset if the SNP were to succeed in taking Scotland out of the UK, but to be honest this is more because of my identification with the UK than because of practical economic reasons.

How to get along (and save the Union)? I think it would at least help if we could recognise that our various national identifications are irrational, but nevertheless legitimate. Once we have made this recognition we can work out how to come to some kind of accommodation which will humour everyone’s irrational identifications, in the same way as was done in the Northern Ireland peace agreement. At least I think it would be better than shouting “I am right and you are wrong” up and down the A1.

“The British Government has made significant concessions already” – could anyone back this statement up? I can’t actually find what concessions Westminster has made, let alone “significant” ones.

Politics and life in general is about compromises. Neither Ms Sturgeon, Mrs May and all the EU representatives don’t want to lose face and appear weak. This attitude gets us nowhere fast and it’s about time everyone woke up and recognised the fact that Brexit is happening because the mega wealthy are looking to protect their money, nicely hidden away in off-shore bank accounts thanks to their minions in the City of London. The up shot is that we “the people” will have to pick up the pieces. As Brexit becomes a reality, and a deal on how the future relationship will pan out seems to become less likely by the week, big business and the public in general are beginning to get a bit edgey and want action, which brings me to my point. Given that the majority of Scottish MPs and MSPs are SNP, that could be recognised as a mandate for independence. If everyone just took a step back and thought rationally for a moment and looked at the situation which is unravelling as I type they would do what normal people do – compromise. Mrs May is being guided by the far right of her party, who want out of the EU single market and customs union. This attitude will effect all businesses negatively in some way. So here are my suggestions for what they are worth that could be the compromise that keeps all party’s happy. First, Scotland becomes independent, (no need for referendums etc) but does not join the EU (not for a while anyway),but instead joins EFTA (where according to Norway they’d be welcome) and has access to the EU through the EEA but also continues to use the pound for the foreseeable future. This solves the SNPs and Scotland’s need to maintain and protect access to both rUK and EU markets. English, Welsh and Northern Irish companies requiring access to EU markets can do so by setting up Scottish subsidiaries (which is cheap and easy) and trade with the EU through them without barriers or having to worry about trade agreements etc etc. Okay so it’s not perfect but better than WTO rules. Also with Scotland still using the pound it means that the oil and trade in general helps to maintain its value. What I’m basically saying is that an independent Scotland in EFTA working through the EEA can be the gateway to the EU and of great benefit to Scotland and Brexit Britain. It’s a workable compromise, where most party’s get most of what they want. As for the nukes they’ll and up staying and the maritime border, that was shifted by Blair and Brown could be kept the same. It’s got to be worth some consideration as the possibility of a no deal Brexit looms and comprises have to be made.

– As soon as i read the role inversion quote of “Brexit is happening because the mega wealthy are looking to protect their money, nicely hidden away in off-shore bank accounts thanks to their minions in the City of London”-

and the UK tory government, richard branson, gina miller, george soros to name just 3 individuals all pushed for remain!- how can you explain that? are they paupers and working class? i think not. Its in the interest of the wealthy (branson, miller, soros et al) corporations and banks that the UK STAYED IN THE E.U. for cheap malleable labour, profit for the high end of town but there are 1000’s of other all across the board that pushed for remain with mega bucks and influence backing them up. The people that were shafted with the EU- you know, the ones that saw their jobs disappear abroad, or who had to take a paycut to remain employed and get a second job just to pay their needs because of the “free trade deal” we were sold in 1974 which since morphed into a free for all, free movement of population, they are the ones that voted brexit. not the millionaires/ billionaires. As you got that basic and evident fact purposely inversed, the rest of your post isnt worth reading.

The Scottish Executive has no foreign policy brief. Foreign policy is not devolved. It’s all deception and lies from them.