Criticism related to the EU’s democratic deficit became more prominent in the aftermath of the financial crisis. According to Firat Cengiz, it is crucial for European citizens to become more involved in policymaking processes if this deficit is to be overcome. However, she points at an inherent problem affecting areas such as competition policy, where the increasing prominence of overly technical language has undermined opportunities for democratic engagement.

Criticism related to the EU’s democratic deficit became more prominent in the aftermath of the financial crisis. According to Firat Cengiz, it is crucial for European citizens to become more involved in policymaking processes if this deficit is to be overcome. However, she points at an inherent problem affecting areas such as competition policy, where the increasing prominence of overly technical language has undermined opportunities for democratic engagement.

The European Union’s democratic deficit reached new dimensions in the aftermath of the 2008 political and financial crisis. The member states’ immediate reliance on intergovernmental methods in crisis management, decreasing solidarity between governments and also partially between the peoples of the creditor and debtor countries, and the lack of any meaningful role for the European Parliament and national parliaments in the governance of the Economic and Monetary Union have collectively contributed to citizens’ fundamental distrust of the European economic and political system. Citizens increasingly rely on mechanisms outside the conventional political system to voice their distrust, as reflected in increasing hashtag activism and the growth of a protesting culture.

The Union’s democratic deficit had been much discussed before the crisis. As an atypical political system that stands somewhere in between an international organisation and a federal state, the Union does not satisfy the criteria of a liberal democracy. In a nutshell, this is because in the absence of a directly elected institution with ultimate legislative power (like national parliaments) and an executive held to account by that legislative (like national governments), it is incredibly difficult for European citizens to make an impact on decisions made in Brussels through the ballot box.

Neither does the Union satisfy the republican democracy model that sees democracy as a collective decision-making process exercised by a demos (a dense harmonious community) to achieve the common good. Some argue that Europe has multiple demoi rather than a single one. In any case, the Union’s diverse citizenship makes it difficult for citizens to communicate with each other in a common political sphere.

The fallacy of input-output and democracy-effectiveness divides

Before the crisis, the Union’s democracy problems were partially assumed away in the light of the input-output legitimacy model. Proponents of this model did not deny that the European Union suffered from low citizen ‘input’ to its policymaking process. But they argued that partially thanks to its technocratic and expertise-driven policymaking process, the Union created a single market and regulatory policies that are in the interests of citizens. According to this perspective, this attributed ‘output’ legitimacy to Union governance. The output-based understanding of democracy was largely inspired by the New Public Management and the European regulatory state theories that perceive the democratic qualities of policymaking and the effectiveness of policies as entirely separate.

Post-financial crisis political developments and citizens’ increasingly vocal stance against the economic and political system require a fundamental shift in how we perceive and talk about the Union’s democratic deficit. First, given the increasing welfare gap and inequality between different European countries and different classes of citizens, insufficient citizen participation in policymaking cannot be excused with the promise of economic welfare. In other words, the Union’s ‘input legitimacy deficit’ can no longer be justified with the promise of ‘output legitimacy’. As forcefully argued by Beetham, it is never a good idea for a political system to build its relationship with citizens solely on the promise of performance, because this would leave the relationship vulnerable to a crisis when the promised performance cannot be delivered.

Secondly, the input-output dichotomy as well as the New Public Management and the European regulatory state models can be questioned at a more fundamental level. The financial crisis and its management alone stand as proofs that expertise-driven policymaking at the expense of citizen participation does not guarantee more effective policies maximising citizen welfare. In the light of post-modern deliberative democracy models the input-output dichotomy, that perceives the democratic qualities of policymaking and the effectiveness of policies as separate, appears to suffer from a fundamental fallacy.

If citizens provide a direct source of information on policies’ effects on their life experiences and welfare how can effective policies be made without sufficient citizen participation solely on the basis of technical expertise? Put differently, how can output legitimacy be achieved without input legitimacy? Deliberative democracy models force us to question the democracy-effectiveness divide and to embrace a more holistic understanding of policymaking in which democracy (input) and effectiveness (output) play mutually reinforcing, and not alternative roles.

In the shadow of the post-crisis political developments, and particularly the Greek experiences, the Union’s economic governance is increasingly criticised for being undemocratic. This burgeoning debate on economic democracy might have significant consequences on the shape of the Union and its relationship with citizens in the near future, for instance by directly impacting the UK citizens’ decision on whether or not to stay within the Union in the context of the forthcoming Brexit vote.

Nevertheless, the democracy discourse focuses almost exclusively on high policy issues, such as the management of the Economic and Monetary Union and the refugee crisis, and it overlooks the democratic qualities of policymaking in less exciting and more technical areas.

Democracy in Union competition policy

The Union enjoys exclusive power to regulate the customs union, monetary policy for the euro, the common fisheries policy, common commercial policy and in the area of competition policy. Although these policies do not attract much public attention due to their technical nature, they have a significant impact on citizens’ daily experiences and their welfare. Since they are exclusively regulated by the Union, democratic input in these areas essentially depends on mechanisms for citizen participation at the EU-level.

Most decisions regarding these policies are increasingly made within inaccessible and opaque networks, bringing together national and EU level officials, bureaucrats, experts and at times interest group members. These networks do not have any relationship with citizens, and at times they make decisions using soft law methods outside the Union’s legislative framework. As a result, they exacerbate the EU’s democratic deficit. Since they are relatively novel governance phenomena, research regarding the democratic qualities of these networks and proposals to increase democracy in network governance are relatively scarce.

In a recent research project, I have critically assessed the democratic qualities of the EU’s competition policy in this light. The project studies the participation of citizens and institutions representing their interests, including the European Parliament and consumer organisations, in the recent reform process of Union competition policy. The reform process transformed the enforcement of EU rules against anti-competitive agreements, abuse of dominant positions and anti-competitive mergers.

Partially inspired by American antitrust policy, the reforms steered EU competition rules toward a neo-liberal paradigm that employs neo-classical economics as the key enforcement methodology to distinguish between harmful (inefficient) and harmless (efficient) behaviour. The European Commission orchestrated the reform process almost singlehandedly and implemented the reforms using soft-law, network governance and coalition-building with the epistemic community of European and American competition law and economics scholars.

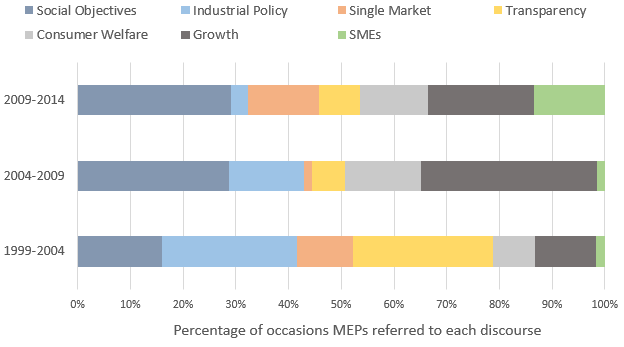

A discursive analysis of competition policy debates in the European Parliament’s Plenary and its Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (between 1999-2014) shows that, in contrast to the European Commission’s insistence on economic efficiency as the key underlying objective of competition policy, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) envision a multi-faceted policy that pursues several objectives including: social objectives (such as employment and environmental protection), industrial policy and internal market objectives, SME protection, protection of consumers, growth, and efficiency. After the crisis, MEPs have voiced social policy objectives consistently and more so than other policy objectives. Additionally, MEPs have complained on several instances over imperfect transparency in the European Commission’s management of the reform process and for being effectively blindsided by the Commission.

Figure: Discourses used in competition policy debates in the European Parliament

Note: For more information see the author’s longer journal article.

Similar to the European Parliament, consumer organisations have also played a minimal role in the reform process. This is not only because consumer vis-à-vis business organisations suffer from serious collective action and resource problems, but is also due to the fact that consumer organisations do not speak the same technical language as Commission officials. They are also not able to provide the technical information and expertise which is much needed by Commission officials in their enforcement activities. Thus, they do not enjoy the same level of access to policymaking as do business organisations.

Technical policy discourses and democracy

The European Commission and other actors primarily relied on the scientific expert discourse of neo-classical economics in the reform process. This technical discourse appears as a key reason for the European Parliament and consumer organisations’ marginalisation in the reform process. As argued by Foucault, all expert discourses, particularly those in the context of economics, tend to be exclusionary, because individuals cannot be a part of the debate and criticise what economics argues without being fluent in its language and methodology.

This jeopardises democracy in policymaking because apparently technical and scientific choices often conceal political choices. As argued by Beetham, most policy decisions reflect a choice regarding the social and economic order and such choices cannot be perceived as purely scientific or technical – and therefore devoid of political content. For instance, the competition policy reform process was very much influenced by the economic policy choices made in the Union’s Lisbon and Europe 2020 Agendas; and Competition Commissioners Monti, Kroes and Almunia heavily relied on the Lisbon and Europe 2020 discourses in their defences of the reform process.

Thus, as a final note, my research project highlights the fundamental importance of an accessible discourse for democracy in policymaking. Network governance lacks the procedural and bureaucratic straightjackets of the EU’s legislative process. Thus, if organised in the light of democratic principles, networks can potentially function as open, participatory platforms giving citizens a real voice in policymaking. But for this to happen, first and foremost, the currently inaccessible, overly technical discourses used by networks should be replaced with accessible, simple, citizen friendly ones.

This call for more accessible policy discourses might nevertheless generate criticism from the perspective that competition and other policies regulating markets and economy are inherently technical. Thus, experts should have the primary say in these policies, as citizens do not have as much to contribute to the discussion. In response to this, I argue that competition and similar economic policies make a significant impact on citizen welfare – or at least this is what the European Commission claims – and this makes citizen participation in policymaking a must. Also, the fact that these policies have become so technical that citizens struggle to be even a part of the conversation in itself stands as proof of the fundamental democracy problems in the making of these policies.

Note: This article was first published by EUROPP and gives the views of the author, and not the position of BrexitVote, nor of the London School of Economics.

Firat Cengiz is Senior Lecturer in Law and Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Liverpool. Her primary research interests are in Europeanisation and multi-level governance. She is the author of Antitrust Federalism in the EU and the US (Routledge, 2012) and the co-editor of Turkey and the European Union: Facing New Challenges and Opportunities (with Lars Hoffmann, Routledge, 2014).

1 Comments