What factors influence how closely the positions of political parties match the positions of their voters? Based on a study of 189 parties across Europe, Ana Belchior identifies some of the key variables that explain congruence between the positions of politicians and voters. Her primary conclusion is that parties in the centre of the political spectrum are more likely to be representative than those on the left or right.

What factors influence how closely the positions of political parties match the positions of their voters? Based on a study of 189 parties across Europe, Ana Belchior identifies some of the key variables that explain congruence between the positions of politicians and voters. Her primary conclusion is that parties in the centre of the political spectrum are more likely to be representative than those on the left or right.

Most democratic theorists regard ‘congruence’ – usually measured as the distance between the positions of political representatives and the citizens they represent – as an important characteristic of political systems which ought to be encouraged. The concept lies at the heart of modern theories of democracy. Put simply, democratic governments are supposed to reflect the interests of their citizens.

As more data becomes available, increasing numbers of academic studies have assessed congruence, in many cases based on a left-right comparison between political representatives and voters within political parties. Using a unique comprehensive approach to comparatively explore the causes of party congruence, I argue that European political parties perform well in terms of representing voters ideologically, and that explanations for congruence should be particularly focused on the party level, not at the institutional or (although to a lesser extent) the individual level.

Studying MPs/voters left-right congruence can raise a number of methodological problems. Critics argue, for example, that ideology is too abstract an indicator to study congruence, and that it says little about real political congruence between parties and voters. This is primarily because of the complexity of ideology, which makes the comparison of two profoundly different sets of actors, such as MPs and voters, problematic (particularly given the lack of political sophistication of voters). Furthermore, unlike MPs, voters are not a coherent collective entity, so their positions have different meanings. Despite these problems, scholars agree that the left-right variable captures the comparative ideological positions of citizens and parliamentarians reasonably well. There is consensus that the left-right variable is a fundamental dimension in the political debate, as well as for placing individuals and parties in the political arena, being widely understood by political actors. Specifically regarding congruence, even if we accept that it cannot be considered synonymous with democratic representation, it can be seen as an approximate indicator of the latter. Studying MP-voter ideological congruence is, therefore, a useful approach in terms of understanding the way democratic representation works.

In the study of party congruence, most research has failed to address a fundamental question: what explains higher and lower levels of congruence between voters and their representatives in political parties? Generally, research has shown that levels of congruence between voters and party positions are low, but vary according to the issue at stake: congruence is higher for ideological or highly politicised issues. Few studies have focused on the causes of party congruence and no research has addressed the topic using a comprehensive approach, which was the goal of my research.

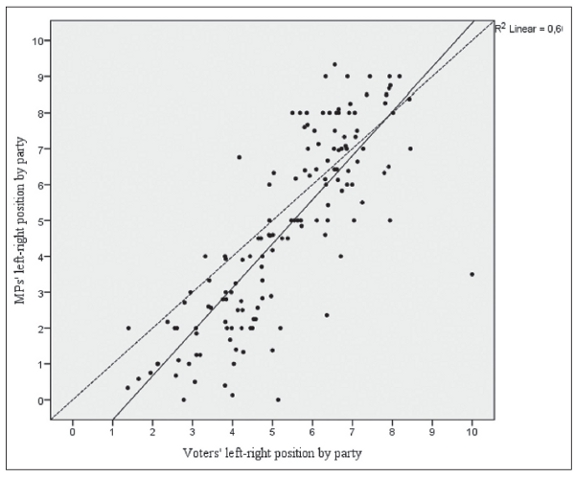

Looking at the levels of congruence generated by political parties in Europe in 2009 (corresponding to 189 political parties in the 27 EU Member States) with a preliminary descriptive purpose, two main conclusions can be stated. First, the spatial distribution of European parties and party systems shows a tendency towards concentration in the ideological centre (especially when it comes to voters). Second, MP positions on the left-right scale appear to be directly and positively related to their voters’ positions, suggesting that relevant levels of ideological correspondence prevail across European political parties, although MPs are ideologically more extreme than their voters. This effect is only slight, showing that MPs tend to be relatively further to the left than their voters (as previous research has demonstrated). Figure 1 below illustrates the location of MPs relative to voters in European party systems.

Figure 1: MP and voter left–right spatial distribution across European political parties

Source: European Election Studies: April/July 2009

Exploring the causality of ideological congruence in a comprehensive way makes it possible to identify the levels and the variables that best explain why some political parties are closer to their electorates than others. Reviewing the literature on this topic, variables at different levels have been used: namely the individual level (characteristics of MPs and voters), party level, and political system level. Looking at these three levels comparatively in the 2009 European party systems, some interesting conclusions emerge, shedding some light to this matter.

The most relevant conclusion is that as the distance of the party from the ideological centre increases, the level of ideological distance between voters and MPs also increases. Given the tendency for bigger parties to be closer to the centre and for smaller ones to be closer to the extremes of the spectrum, party dimension also shows that congruence with voters increases with the size of the party. Similarly, lower levels of MPs’ intra-party polarisation tend to produce higher MP-voter congruence. These findings suggest that what explains MP-voter congruence is fundamentally the placement of parties at the ideological centre, where most of the electorate is located. Radical parties tend to locate themselves away from centrist voters and, thus lose voter congruence.

Voters’ political sophistication and involvement proved to be irrelevant, as did MPs’ political experience. These findings contradict the intuitive expectation that politically attentive voters would be more capable of selecting a party congruent with their own ideological self-placement, and that experienced MPs would be more capable of situating themselves closer to their voters. Interestingly, MPs’ perceptual accuracy on voters’ left-right position is particularly important, suggesting that the more accurately MPs perceive the ideological placement of voters, the closer they position themselves to voters. Previous research has shown that MPs tend to think that their voters are located in close proximity to their positions. As electorates tend to be more centrist than their MPs, politicians that adopt more centrist positions naturally tend to increase the accuracy of their perception of the positions of voters. These conclusions support Miller and Stokes’ seminal assumption that the accuracy of the perception of legislators is potentially connected with the quality of political representation (1963).

Among the system level characteristics, the conclusion is that more differentiated party systems and proportional representation systems do not produce higher MP-voter congruence than the non-differentiated, majoritarian systems. Indeed, majoritarian systems correlated positively with congruence (perhaps because, like voters, they are centre-oriented).

Taken together, the conclusions indicate that the tendency for electorates to be at the centre of the ideological spectrum is a crucial element in understanding the level of party congruence, given that the centre is the territory of ideological congruence for parties.

For a more detailed discussion of this research, see the longer paper: Belchior, A.M. (2013) ‘Explaining left–right party congruence across European party systems: a test of micro-, meso-, and macro-level models’, Comparative Political Studies, 46(3): 352-386.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/12RG0mY

_________________________________

About the author

Ana Belchior – ISCTE – University Institute of Lisbon

Ana Belchior – ISCTE – University Institute of Lisbon

Ana Maria Belchior is an assistant professor at ISCTE-IUL (Lisbon University Institute) in Lisbon and senior researcher at CIES-ISCTE-IU. She has been involved in research on several projects related to the themes of democracy and globalization, political participation, democratic representation, and political congruence and has published her findings in diverse national and international journals.