Syriza won power in the Greek elections on 25 January, however the new Greek government faces significant challenges both in terms of the country’s domestic situation and negotiations with its European partners. Daphne Halikiopoulou and Sofia Vasilopoulou write on the key policies that are likely to be pursued in the aftermath of the elections. They note that while much will depend on reaching a deal over the repayment of Greek debt, retaining the support of the middle class voters who backed Syriza in the election will also be critical at the domestic level.

Syriza won power in the Greek elections on 25 January, however the new Greek government faces significant challenges both in terms of the country’s domestic situation and negotiations with its European partners. Daphne Halikiopoulou and Sofia Vasilopoulou write on the key policies that are likely to be pursued in the aftermath of the elections. They note that while much will depend on reaching a deal over the repayment of Greek debt, retaining the support of the middle class voters who backed Syriza in the election will also be critical at the domestic level.

Greece has a new government: a radical left-radical right coalition between the Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) and the Independent Greeks (ANEL). The 25 January elections were the most critical in decades, not only for Greece but also for Europe. Greece is the first country among the European ‘debtors’ to elect a government with a clear anti-austerity mandate. There are expectations of a potential domino effect: already Podemos has promised to emulate Syriza’s victory in the upcoming 2015 Spanish national elections.

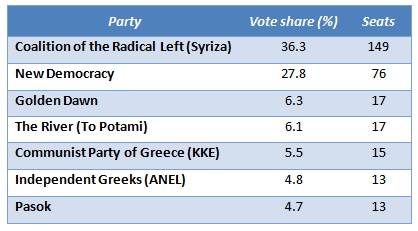

Syriza, previously marginalised in the party system, managed to attract just over 36.3 per cent of the Greek vote, which translated to 149 seats – two seats short of forming a majority government. The centre-right New Democracy, which was in power since 2012 and has been associated with austerity and harsh economic measures, came second with just over 27.8 per cent of the vote. Essentially the result was a landslide for Syriza, which managed to attract a broad voting base. The table below shows the final results.

Table: Results of the 2015 Greek parliamentary elections

Note: Only parties who gained seats in parliament are shown. For information on the parties see: Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA); New Democracy; Golden Dawn; The River (To Potami); Communist Party of Greece (KKE); Independent Greeks; Pasok.

As the table indicates, it was not only the far left that benefited from the election. The ultra-nationalist extreme right-wing Golden Dawn came third with just under 6.3 per cent of the vote, translating into 17 seats. While it has lost support marginally since the 2012 elections, the result indicates that the party now has consistent support. This is despite the fact that its leading members are currently imprisoned facing indictment and the party did little campaigning.

The River, a centrist party putting forward a socially liberal agenda, came fourth with only around 0.2 per cent less than the Golden Dawn and received the same number of seats at 17. This indicates low levels of support for the centre ground. The overall election results are hardly surprising given the context within which they took place: high levels of unemployment, disillusionment and social discontent. Both the campaign as well as the resulting coalition confirm the strength of the pro and anti-bailout cleavage.

The campaigns

The debate took place along the lines of continuity versus change, stability versus instability, euro versus Grexit, austerity versus growth, and fear versus hope. During the short pre-election period, discussions were structured around the contrast between hope for a better future, on the one hand, and fear for a worse future to come, on the other. This illustrates the extent to which emotions were at the heart of party campaigns. Parties tapped into people’s insecurities in an attempt to attract their vote. It is precisely the fear versus hope campaign that has polarised the debate.

Syriza was the advocate for ‘hope’: the party’s logo ‘Hope is on the way’ was accompanied by rhetoric emphasising a new beginning, justice and equality, an end to the humanitarian disaster that austerity has created, a new Europe and a future with dignity. On the other hand New Democracy attempted to mobilise on the basis of fear. Its campaign, which in sum was characterised by scaremongering, was centred on the potential consequences of a Syriza victory, including the downgrading of Greece’s credit rating, a Greek default, a Grexit, and an overall economic disaster which would ‘undo’ the sound economic policies that the New Democracy-led coalition government had been implementing since 2012. It appears that hope is a stronger emotion than fear and Syriza’s campaign was the most successful.

The new Syriza-led coalition government

What unites Syriza and ANEL is their anti-austerity stance. But what divides them is their viewpoints on key social issues, including nationalism, religion and immigration. The Independent Greeks are a radical right party emphasising what they term ‘national issues’: for example the Macedonian question, Cyprus, and Greece’s relationship with Turkey, which they have identified as non-negotiable ‘red lines’. This party may be classified as conservative authoritarian, emphasising the motto ‘fatherland, religion and family’. These terms would seem to fundamentally contradict Syriza’s left wing socially open ideals, such as their pro-immigration stance, their calls for the separation of Church and State, and support for same sex marriage. Alexis Tsipras is the first Greek Prime Minister ever to take a political rather than a religious oath for his new government.

However, it was more strategic rather than ideological considerations that guided the formation of the coalition. The inclusion of Rahil Makri, a former ANEL MP, in Syriza indicates that the party is guided more by the pro versus anti-austerity cleavage rather than the left-right cleavage. Alternatively, this could be a good indication that Syriza is becoming a catch-all party attempting to attract a social base broader than its traditional left-wing supporters.

Even before the elections Syriza had started to compromise on its more radical positions. When it entered the Greek political scene as a contender in 2012, it did so on a radical left platform bearing all the features of a party in opposition. Emphasising anti-establishment ideas, Syriza had declared that it would renegotiate austerity at any cost. As the party got closer to power, it began to resemble a party in office: moderating its position in a bid to attract broader electoral support and put forward policies it can actually implement.

Even if we accept that Syriza is moderating, it is still fundamentally distant ideologically from ANEL and this casts doubt on the stability of the coalition. In addition, Syriza’s decision to make the Ministry of Defence the responsibility of ANEL’s leader, Panos Kammenos, raises questions about the future of foreign policy and the so-called ‘national questions’.

A possible Grexit?

But what Europe is really interested in is Syriza’s economic agenda. The party has pledged to take Greece out of austerity and alleviate poverty. Among other pledges, it has promised to restore some of the lowest pensions, return public sector jobs, stop taxing incomes up to 12,000 euros, offer free electricity to 300,000 households, provide food allowances to poor families, free healthcare for all and housing subsidies to up to 25,000 families. It has also promised to address the issue of property tax (ENFIA) and not allow the auctioning of primary residences. The key question that arises from all this is where Syriza will get the money from.

The party has said it will tax the rich and give to the poor. But the obvious questions are who are the rich, how much are they going to be taxed, how will the problem of tax evasion among the rich be addressed, and what is going to happen to Greece’s large middle class that has suffered from austerity. The party has not been clear about its programme for structural reform or about precisely how it will boost economic growth.

The key is a balance between external demands and domestic politics. On the one hand, Syriza will need to renegotiate with the country’s European partners on the issue of prolonging debt repayments. Domestically, on the other hand, the regulator will be the middle class. If we accept politics 101, the middle class plays a determining role for both economic growth and democratic stability.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1zbEf1u

_________________________________

Daphne Halikiopoulou – University of Reading

Daphne Halikiopoulou – University of Reading

Daphne Halikiopoulou is Lecturer in Politics at the Politics and International Relations department at the University of Reading. Her work examines contemporary issues related to the study of nationalism and radical politics in Europe. She is author of Patterns of Secularization: Church, State and Nation in Greece and the Republic of Ireland (Ashgate 2011) and co- editor of Nationalism and globalisation: conflicting or complementary (Routledge 2011 with Sofia Vasilopoulou).

Sofia Vasilopoulou – University of York

Sofia Vasilopoulou – University of York

Sofia Vasilopoulou is a Lecturer at the University of York (Department of Politics). She teaches quantitative and qualitative research methods, Comparative European Politics and EU Politics. Her research interests include political behaviour and party politics. She holds a PhD in European Studies from the London School of Economics. Prior to joining York, she was a Fellow in Comparative Political Analysis in the School of Public Policy, University College London. She currently works on a number of projects examining the theme of political dissatisfaction with democracy and democratic institutions across Europe.