The use of modern technology in politics has become increasingly important in recent years, but what new opportunities could technology have for the political parties of the future? Taking inspiration from a statement by the Five Star Movement’s Beppe Grillo, Andrea Ceron outlines what an algorithm for expelling rebel MPs and rewarding loyal party members could look like. He argues that while Grillo’s comments were regarded as far-fetched, it is not too far from reality that technology could soon be used by political parties in this way.

In May 2016, the founder of the Five Star Movement (M5S), Beppe Grillo, outlined an idea to create an algorithm that would be capable of expelling rebel Members of Parliament from the party. Taking his cue from Bitcoin’s ‘blockchain’ scripts, Grillo argued that an algorithm could monitor the actions of elected officials. While M5S activists are currently involved – through online voting – in the decision to expel mavericks, this new algorithm would automatically do that (without any human intervention) whenever politicians’ behavior is not in line with the party’s manifesto.

The M5S is a pioneer in the use of new technologies for political purposes. Nevertheless, one of its main party leaders, Luigi Di Maio, downgraded Grillo’s statement to a “comedian’s joke” questioning the seriousness and the feasibility of such proposal. Was this just a joke? My answer is “no” and in a recently published article I Illustrate how and to what extent an algorithm can perform this and other similar tasks.

Far from any normative intent, I will show that textual analysis of the comments published online by MPs allows us to evaluate a politician’s distance from the party leadership. As such, we can foresee which politicians will defect and exit from the party and which ones will get promoted to office, based on their degree of party loyalty displayed on social media. Accordingly, it is not too far from reality that an algorithm could be used to identify and expel rebel MPs and to reward the most loyal ones.

To perform this analysis, I took advantage of two recent technological developments. First, the rise of social networking sites, with an increasing number of politicians that are nowadays active and express opinions online. Second, the improvements in the field of text analysis, which allow us to extract political positions from textual documents.

Given that political language (even online) is largely ideological in nature, the rise of social networking sites, such as Twitter, represents a new opportunity to extract information on the preferences of political actors. This is particularly true for ‘‘hidden actors’’, such as formal and informal intraparty subgroups, and individual politicians, whose ideological viewpoints may not always be recorded in official documents or displayed through parliamentary behaviour.

In light of this, I collected the comments published by Italian politicians on social media between 2012 and 2014. These comments have been analysed through Wordfish, an automated scaling technique of text analysis. By comparing the relative frequencies of words across documents, Wordfish locates texts on a single ideological dimension, thereby allowing us to measure the distance of each politician from the party leadership.

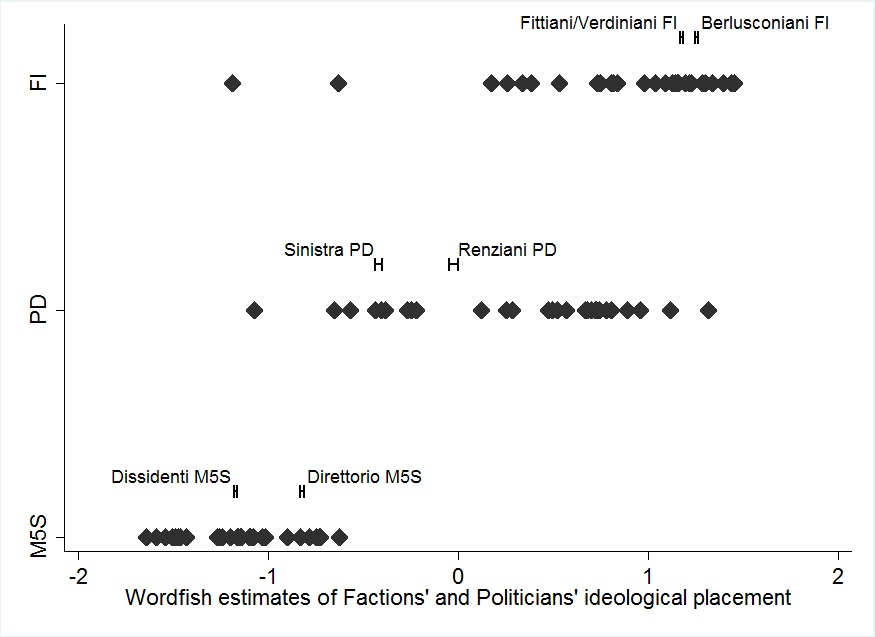

Statistical analyses suggest that online statements are informative of intraparty divisions and help to understand several intraparty dynamics. For instance, Figure 1 sheds light on defections in the parliamentary arena. It displays the ideological placement of politicians and factions belonging to the three main parliamentary parties at the end of 2014: the Democratic Party (PD), Forza Italia (FI) and M5S. MPs located further away from their party leader were indeed more likely to defect in parliamentary votes and to switch off from their parliamentary party groups.

Figure 1: Ideological placement of politicians and factions in the three largest Italian parties at the end of 2014

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article.

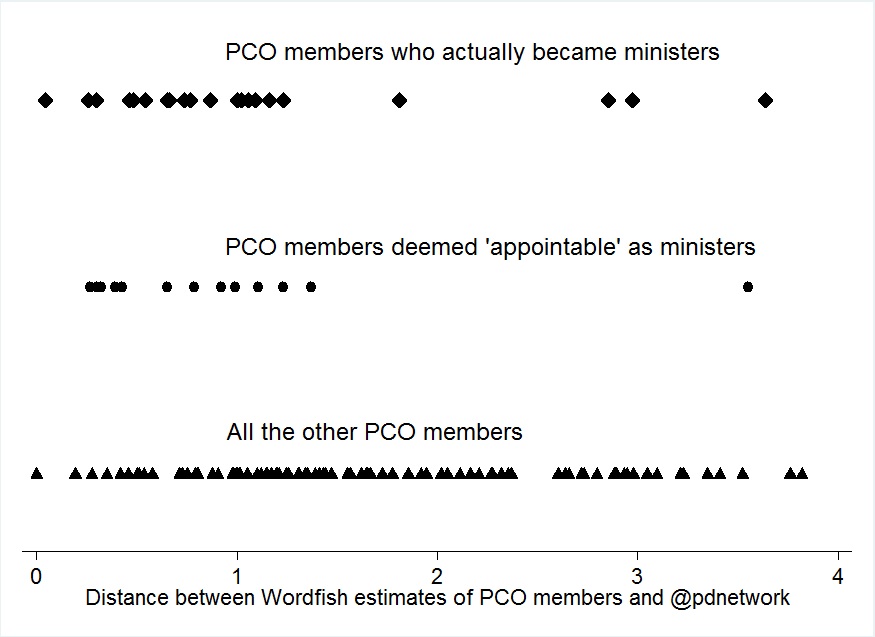

Conversely, Figure 2 sheds light on promotions by focusing on the Party in Central Office (PCO). It reports the distance of each member of the Direzione PD from the PD Official Twitter account (@pdnetwork). Results reveal that a politician’s probability to be deemed as a credible candidate for a ministerial position by the media, or to be actually appointed as a minister of the Renzi cabinet in 2014 grows along with the similarity between the content of his/her Twitter profile and that of the party.

Figure 2: Distance between members of PD Direzione and the PD Twitter account

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying journal article.

These results point to the potential of Twitter as a source of data to study intraparty politics and the careers of politicians. In fact, social media data retain some key advantages. First, online messages are unmediated, spontaneous, and sometimes impulsive statements. These features increase the likelihood that such public declarations reflect the true preferences of political actors, particularly if compared to the interviews released to traditional media where politicians also have to answer unwanted questions.

Analogously, although some online statements may be instrumental, the extent of strategic behaviour online could be lower compared to what happens offline in more formal environments. Furthermore, social media data allow us to record changes that happen day-by-day. This makes them particularly suitable for studying politics in fluid party systems and investigating career advancements.

In sum, by scrutinising social media comments, party leaders can make inferences as to the degree of loyalty expressed by their MPs. Rewards and punishments could be assigned accordingly. Would this be ethically controversial? I don’t think so. Rather than restraining intraparty democracy, this would enhance transparency and accountability. Social networking sites, in fact, provide backbenchers with the opportunity to build their reputation, in terms of showing loyalty towards the leadership or expressing dissent to boost their popularity among rank-and-file members.

What is more, as politicians take clear positions on social networking sites, intraparty dynamics become less hidden and the gears of political systems may appear more transparent. In turn, politicians and political actors can be made accountable for their actual behaviour, in light of the positions expressed online.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Andrea Ceron – University of Milan

Andrea Ceron – University of Milan

Andrea Ceron is Assistant Professor at the University of Milan. He is co-founder of Voices from the Blogs Srl, which is a spinoff from the University of Milan that analyses social media through quantitative text analysis of posts and tweets. His research interests include intra-party politics, party competition, electoral campaigns, judicial politics, media bias and social media analysis. He is on Twitter: @AndreaCeron83