Academic blogging gets your work and research out to a potentially massive audience at very, very low cost and relative amount of effort. Patrick Dunleavy argues blogging and tweeting from multi-author blogs especially is a great way to build knowledge of your work, to grow readership of useful articles and research reports, to build up citations, and to foster debate across academia, government, civil society and the public in general.

Academic blogging gets your work and research out to a potentially massive audience at very, very low cost and relative amount of effort. Patrick Dunleavy argues blogging and tweeting from multi-author blogs especially is a great way to build knowledge of your work, to grow readership of useful articles and research reports, to build up citations, and to foster debate across academia, government, civil society and the public in general.

One of the recurring themes (from many different contributors) on the LSE Impact of Social Science blog is that a new paradigm of research communications has grown up — one that de-emphasizes the traditional journals route, and re-prioritizes faster, real-time academic communication. Blogs play a critical intermediate role. They link to research reports and articles on the one hand, and they are linked to from Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Tumblr and Google+ news-streams and communities. So in research terms blogging is quite simply, one of the most important things that an academic should be doing right now.

But in addition, STEM scientists, social scientists and humanities scholars all have an obligation to society to contribute their observations to the wider world. At the moment that’s often being done

- in ramshackle and impoverished ways

- in pointlessly obscure or charged-for forums

- in difficult language where you need to look up every second word in Wikipedia. Some of this is necessary for condensed specialist communication. But much of it is just unneeded jargon and poor writing dressed up as necessary vocabulary

- with acres of ‘dead-on-arrival’ data (that will never be used by anyone else in the world), often presented in unreadable tables

- and all delivered over bizarrely long-winded timescales. From submission to publication in some top economics journals now takes 3.5 years. At the end of such a process any published paper is no more than a tombstone marking where happening debate and knowledge used to be, four or five years earlier.

So the public pay for all or much of our research (especially in Europe and Australasia). And then we shunt back to them a few press releases and a lot of out-of-date, arcanely phrased academic junk.

Types of blogs

A lot of people think that all blogs are solo blogs, but this is a completely out of date view. A ‘blog’ is defined by Wikipedia as:

‘a truncation of the expression web log… [It] is a discussion or informational site published on the World Wide Web and consisting of discrete entries (“posts”) typically displayed in reverse chronological order (the most recent post appears first). Until 2009 blogs were usually the work of a single individual, occasionally of a small group, and often covered a single subject. More recently “multi-author blogs” (MABs) have developed, with posts written by large numbers of authors and professionally edited. MABs from newspapers, other media outlets, universities, think tanks, advocacy groups and similar institutions account for an increasing quantity of blog traffic. The rise of Twitter and other “microblogging” systems helps integrate MABs and single-author blogs into societal newstreams’. [Accessed 29 August 2014]. (Let me pause here to reassure some academic readers who may be bristling at being asked to read Wikipedia text – I know this passage is sound since I co-wrote much of it).

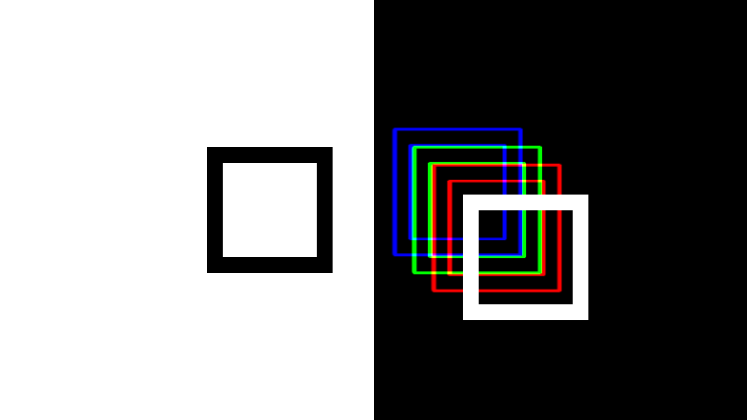

Actually the evolution of academic blogs specifically has now progressed even further, so that we can distinguish group or collaborative blogs as an important intermediate type between solo blogs and multi-author blogs. The two tables below summarize how these three types of blogs now work, drawing attention to their very different advantages and disadvantages.

Why blogging works in academia

Blogging (supported by academic tweeting) helps academics break free from all the legacy practices I covered at the beginning of this post, although to differing extents, because:

- It’s quick to do in real time. It taps academic expertise when it’s relevant, and so lets academics look forward and speculate in evidence-based yet timely ways. Esoteric knowledge and accumulated wisdom that might previously have been shared with four or five people over lunch in the Senior Common Room, or the PhD hangout, now gets out into the public domain, and can be read, tracked, emulated or contested.

- It communicates bottom-line results and ‘take aways’ in clear language, yet with due regard to methods issues and quality of evidence. Twitter is a huge supplementary help, in forcing academics to communicate key messages in 140 characters!

- Multi-author blogs especially help create multi-disciplinary understanding and the joining-up of previously siloed knowledge. They hugely reduce the barriers involved in keeping abreast of a wide range of knowledge, or in finding out for the first time about a subject or debate or field of work that is new to you. All the LSE family of blogs, for instance, cover 40+ different social sciences (and some related) areas like architecture, city planning and technology. Our EUROPP blog pools within this large discipline group for 50 countries in Europe, and our USAPP blog has the same focus for the United States, Canada and Mexico. The LSE Review of Books and the LSE Impacts blog both range even more widely, incorporating history, philosophy, media and cultural analyses that span across the social sciences and the humanities, and some fringe aspects of the huge STEM disciplines group. An enlarged disciplinary range that was once just the province of a few exceptional publications and magazines (like Scientific American or the Economist) becomes a lot more accessible to a much wider audience. Group blogs have lesser cross-disciplinary effects, because they are rarely widely visible — usually only insiders find them. But they contribute greatly to better communication within disciplines, and so they can help reduce barriers to learning by being passed on to well-informed or persistent outsiders to the discipline.

- Blogging thus creates a vastly enlarged foundation for the development of ‘bridging’ academics, with real inter-disciplinary competences, honed by lots of interactions with people in other academic silos. By the 1980s the siloing of science and scholarship in reductionist mode meant that there was a sharply diminished potential for inter-disciplinary understanding. At that low point the bridging role was exploited only by a few ‘public intellectuals’ (on whom excessive attention is still focused). But now this key ‘bridging’ role is once again beginning to become a far wider-scale competency.

- Blogging can also support in a novel and stimulating way the traditional role of a university as an agent of ‘local integration’ across multiple disciplines. This capability is especially important now at the many interfaces between the social sciences and the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) disciplines, where co-operation across silos and growing genuinely trans-disciplinary research are increasingly salient for societal progress.

Academic blogging gets your work and research out to a potentially massive audience at very, very low cost and relative amount of effort. With platforms like WordPress, you can set up a very simple solo blog and have your first article online in no more than 30 minutes. With Medium (which of course I’m using here) the threshold is even lower , maybe 10 minutes. As soon as you register in Medium you get a blank screen bearing the heartening message ‘Bang out some text!’ That’s what I did in January this year, and since then many tens of thousand people have downloaded these posts (e.g over 21,000 in just the last month). The key difference between the two is that Medium is just for communicating text — it has a very simplified editing function, and you can’t easily control how your texts are listed. It’s best for people who either have no Web competencies or don’t want to devote any time to refining the ‘look and feel’ of their work online (I plead ‘guilty’ on both counts). If that’s not you, then a WordPress solo blog is surely the route for you to follow.

Recent research from the World Bank has shown that blogging about an academic article can lead to hundreds of new readers when before there were only a handful. Blogging and tweeting from multi-author blogs especially is a great way to build knowledge of your work, to grow readership of useful articles and research reports, to build up citations, and to foster debate across academia, government, civil society and the public in general.

Six tips for academic blog editors

I’m not an expert here, although I have helped design the format of LSE’s top blogs, along with a great team of folk — whose wisdom and expertise I’ve tried to briefly summarize here:

- Make sure your titles tell a story, and that the findings of each post are communicated early on. Academics normally like to build up their arguments slowly, and then only tell you their findings with a final flourish at the end. And they often show great dedication in choosing obscure titles for their work. Don’t do this ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’ in which layers of irrelevance are progressively stripped aside for the final kernel of value-added knowledge to be revealed. Instead, make sure that all the information readers need to understand what you’re saying is up front — you’ll make a much stronger impression that way. In a group or multi-author blog content will often be eclectic and needs to be signposted to readers in really effective ways. So here the editors should always write the titles for posts (clearing them with the authors if you must). In all the big LSE blogs the editors also write an initial summary paragraph for readers, which is not cleared with authors because it is our understanding of what their key messages or findings are, and is clearly signposted as such. In a solo blog you are your own editor, always a problem. My advice would be to ask your partner or a friend for advice on the titles of important posts. Also see how people retweet you — their re-phrasings and summaries can often show you a better way of capturing what your post says.

- Readers should never be in any doubt about who has written a blog. In multi-author blogs and group blogs, always give a decent short Bio of the authors, ideally including a photograph. It is important to tell readers clearly who the author(s) are, where they come from, how to contact them and to give URL links to their other recent books or work. In solo blogs make sure that you provide a clear explanation of who you are (again including a photograph), what the blog aims to do and how to contact you via email and social media. This may seem obvious stuff but in fact it is not. Often in group blogs it is very hard indeed to work out who has actually written the text, and the author name is buried away in an obscure corner. And very, very often in solo blogs, readers who arrive at a particular post from Google or social media then have to launch off on a prolonged search of obscure corners of the blog just to find out who the author is.

- Because blog contents should be timely, make sure that the date for content displays prominently at the start of content. Don’t just put a date in an obscure way at the bottom of the post, or even in some separate listing of posts (as I’ve seen on some WordPress solo blogs). Clearly dating posts is especially important if the blog is dealing with fast-moving social developments, or an ever-changing research frontier in academia, where earlier content may be less valuable than the more recent material. And however fancy your blog design gets (e.g. with picture-based titles and rotating slides) make sure that when people reach it they can easily view it in a date-order format that will load quickly on a smart-phone or tablet. (This is a lesson we lost sight of in a recent LSE blog re-design, and we are now locked in to a elaborate format design that does not do this and will take us some time to rectify).

- Remember the Web is a network, not a single-track railway line — and not everyone uses the web in the same way. So once you have a blog post, do everything you can to get the key content out to diverse readerships who want to see it. Post your links to Twitter (several times, at different times of the day) and Facebook, whose timestream format is excellent for blogposts. Let people subscribe by RSS or email.

- Wherever possible deposit all blog content of lasting academic value in a university e-depository, so that it can be picked up and listed by Google Scholar. Any good multi-author blog run by academics or universities should already have a fully consistent stream of content, and so should already be depositing all blogposts. If you run a MAB and are not yet doing this, you’re missing a trick, so talk to your library about changing that. If you run a group or solo academic blog this may be more tricky because posts are often not that consistent in terms of length or the lasting academic value of the content, and your local e-depository may be correspondingly sniffier about hosting any materials. You need to find a way to select the best materials you have generated and talk to your library or e-depository about getting them permanently archived.

- Talk to your readers. Encourage people to comment (but only post their comments after moderation) and respond to comments and to Tweets. Talk to people on Twitter and Facebook when they discuss your work. And be reciprocal, open-minded and fair in sharing your content with others and linking to their work — improving the public understanding of university research is a huge collective good for academics across all disciplines. We can all flourish together in the new paradigm for academic work.

I sincerely thank Chris Gilson, with whom I co-wrote an earlier version of many of the ideas in this post.

This piece originally appeared on the Writing for Research blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science at the LSE and is Chair of the LSE Public Policy Group. He is well known for his book Authoring a PhD: How to plan, draft, write and finish a doctoral dissertation or thesis (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

You left out educating the public. Blogs by professionals – lawyers, economists, political scientists, natural and physical scientists provide information to the public that is not available elsewhere. Those of us who are interested in reading “below the fold” so to speak, have gained broad knowledge in these fields which are not our own.

A good and thoughtful post, thank you. Just one comment: can you please update it to use tables with actual text instead of images? Right now it is needlessly preventing visually impaired readers from accessing any of that content. Thanks!

WordPress is too “hard” and “heavy” to install and use. Something like Ghost.js (https://ghost.org/) and Pelican ( http://blog.getpelican.com/) could be even easier to use and setup.

Really interesting post, thanks, and I certainly agree about the importance of blogging for academics. But it did amuse me that you state:

“Because blog contents should be timely, make sure that the date for content displays prominently at the start of content. Don’t just put a date in an obscure way at the bottom of the post….”

It took me a long time to find the date of this piece, at the bottom…. 🙂

I wonder if the advent of blogs and tweets gave rise to criticisms leveled at traditional academic writing both here and by distinguished intellectual, Harvard academic Stephen Pinker. No need for the dance of the seven veils, with the barrage of information. Get to the point fast. I wonder about the influence of blogs and tweets on the writing in academic journals. Are blogs and tweets changing academic writing?

Thanks for all these tips and the time u spent on writing them. Many of us could really use these for having better blogs!

Including blogs within formal academic writing allows authors to utilize ideas that may not yet be available through traditional channels, and provides source materials for those without access to content hidden behind publishers’ blockades. We help student in assignment and thesis writing