Suriname’s government and civil society are beginning to tackle the longstanding but newly acknowledged issue of suicide. But social stigma remains strong within the Indian community, and facing up to cultural barriers will be key to the success of suicide-prevention programmes, writes Bhavik Doshi.

Suriname’s government and civil society are beginning to tackle the longstanding but newly acknowledged issue of suicide. But social stigma remains strong within the Indian community, and facing up to cultural barriers will be key to the success of suicide-prevention programmes, writes Bhavik Doshi.

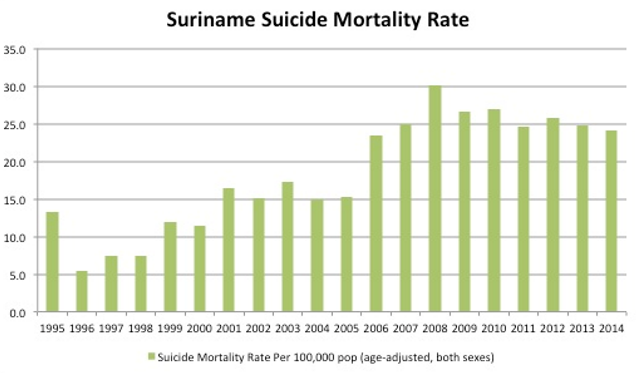

Few would expect to find the small Dutch-speaking South American nation of Suriname amongst the countries with the highest rates of suicide in the world. But with 27.8 suicides per 100,000 people, Suriname found itself sixth in the World Health Organisation (WHO) ranking in 2012, even after decades spent battling this insidious epidemic.

But in this highly diverse country of Indians, Javanese, Creoles and Maroons, suicides within the Indian community (known as Hindostanis) make up almost 70 per cent of the total. The district of Nickerie represents a regional hotspot, as adolescents and young adults are especially vulnerable.

The most common way for Indians to take their own lives is by ingestion of pesticides, as many work in agriculture. Other forms of suicide include use of firearms and more recently jumping from the Jules Wijdenbosch bridge, recently dubbed a “suicide magnet” by local media.

But why is this happening and how can it be prevented? Professor Tobi Graafsma of Anton de Kom University highlights poverty, alcohol abuse, domestic violence, lack of opportunities, poor economic conditions, access to pesticides, and the rigidity of Hindostani culture as the general risk factors.

But in the course of my own research, the nature of Indian society in Suriname has also allowed the social stigma of suicide to prosper. With Hinduism particularly influential, prevailing religious and moral values make suicide unacceptable with human life considered sacred and precious: a gift from God.

Yet, other norms and values of Indian culture create tremendous pressure to live up to the expectations set by family, friends and the community. Young men both in the capital, Paramaribo, and in Nickerie repeatedly referred to pressures to find a job and get married, as this equated to status and wealth. Those not meeting these ‘requirements’ are deemed unworthy, and their lives a personal and social disappointment.

My research also found that when the issue of suicide was raised amongst Indians, there was a clear division in their reactions: either they acknowledged suicide and sought to remedy the problem or they refused outright to acknowledge existence of any problem. This difference also relates to postures on modern life versus tradition, with this growing divergence affecting social cohesion.

The traditional attitude of denying the problem is not new. From the 1920s to the 1960s suicide was rife among young Indian women forced into marriage by their parents. Instead of addressing the problem, the political elite preferred avoiding the risk of stigmatising the Indian community, thereby avoiding social and political conflict during the crucial nation-building period.

Research into suicidal behaviour and suicide prevention only began around the millennium. The state’s denial delayed any action until the problem began to spiral out of control. This also means that many incidences of suicide have gone unrecorded, marked only by silence and invisibility within the Hindostani community.

In the absence of government intervention, it is local NGOs that have taken most of the responsibility for suicide prevention since the mid-2000s. The Mind Console Centre of the Swarnapath Foundation (MCC), for instance, was created in 2008 in response to rising suicide rates, whereas Win Groep forged a collaboration focusing on health, welfare and culture out of three organisations in Nickerie. These two NGOs are community-led and focus on tackling suicide at a grassroots level by better educating vulnerable groups and providing psychosocial support. But at state level the picture was very different, and as late as 2015 there was just one hospital offering psychological support to those attempting suicide and their families.

Albeit as a result of pressure from the World Health Organisation, the government has now begun to take steps to tackle the issue of suicide. The key tool is the National Suicide Prevention and Intervention Plan, which seeks to reduce the suicide rate by 10 per cent over five years through a focus on five key areas:

- Increasing access to mental-health care

- Constraining access to lethal means or agents

- Changing perceptions and attitudes

- Improving cultural and economic empowerment of vulnerable groups

- Carrying out research on suicide

This policy shift is certainly welcome, and it puts the country in a better position than ever to deal with suicide. Yet, the third issue of attitudes is particularly difficult because these are so profoundly rooted in Surinamese society.

The tight-knit nature of the Hindostani community in particular is incredibly difficult to break down, especially for non-Indians. The taboo around suicide has also persisted for generations, meaning any actions aimed at raising awareness and knowledge about the issue will need to be long-term.

As such, despite the government’s recent interest, grassroots organisations continue to be the best placed and most experienced actors in terms of reaching out and changing mindsets. This has already begun to increase understanding of suicide in wider society, and there is growing optimism in Suriname about the possibility of achieving the changes needed to tackle this serious and chronic issue at last.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

It’s. informative it has to be tackled