Local concepts of gender justice in violent contexts can form the basis of strong collective identities and effective forms of politics. But relative isolation from state funding and institutions means that this type of grassroots activism tends to occur beneath the radar of major international forums, events, and programmes. Now is the time to take local forms of gendered activism, resistance, and politics more seriously in order to better integrate them into the global women’s rights agenda, write Nicholas Pope (SOAS) and Julia Zulver (UNAM and University of Oxford), following on from their participation in the LSE LACC, PUC-SP, UNICAMP Researcher Links Workshop on Governance, Crime, and International Security.

Local concepts of gender justice in violent contexts can form the basis of strong collective identities and effective forms of politics. But relative isolation from state funding and institutions means that this type of grassroots activism tends to occur beneath the radar of major international forums, events, and programmes. Now is the time to take local forms of gendered activism, resistance, and politics more seriously in order to better integrate them into the global women’s rights agenda, write Nicholas Pope (SOAS) and Julia Zulver (UNAM and University of Oxford), following on from their participation in the LSE LACC, PUC-SP, UNICAMP Researcher Links Workshop on Governance, Crime, and International Security.

• Também disponível em português

With the world reaching the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Platform for Action to end gender inequality and the 20th anniversary of the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda, an article in The Guardian recently felt able to claim that “[w]orld leaders, civil society and the private sector are preparing to make 2020 the biggest year yet for the advancement of women’s rights.”

Attention-grabbing articles like these seem to herald a watershed moment for the entrenchment of women’s rights internationally, yet significant structural, political, social, and cultural barriers to this progressive global agenda persist the world over.

The local-global disconnect

One step towards overcoming these barriers would be to try to learn from local concepts of gender justice, including the ways in which they can underpin collective identities and locally specific forms of politics. Instead, this type of “grassroots” activism, which typically lacks funding or support from the state, has tended to fall out of sight of the global women’s rights agenda.

Violent contexts in particular present a significant disconnect between the international women’s rights agenda and the local realities of being a woman and surviving. The shooting of feminist artist Isabel Cabanillas de la Torre in Ciudad Juárez in January 2020 served as a tragic reminder of that disconnect, and it was followed this month by major protests in Mexico City following the horrific murder and mutilation of Ingrid Escamilla. On average, ten women a day are killed in Mexico alone.

Although there is good reason to applaud the efforts of international organisations and donors towards the women’s rights agenda, this community could also reflect more profoundly on the precarious, dangerous, and vulnerable situations in which many women find themselves at the local level.

Projects aiming to address gender imbalances in violent and conflictual environments are of particular relevance, as they can involve difficult physical access, insecure implementation, and challenging ethical dilemmas. It is in these spaces that there should be concern about essentialising the role of women as peacebuilders in their communities, especially where there is little consideration of their potential exposure to a range of additional burdens and vulnerabilities.

Violence and the risk of social change

One key lesson that has yet to be fully incorporated into the global women’s rights agenda is that violence takes many different shapes and forms within women’s lives.

The direct and physical forms of violence that emerge through armed conflict can be particularly acute for women. But feminist scholars such as Cynthia Cockburn remind us that violence exists along a continuum for women, with insecurity and gender-based forms of violence sometimes persisting long into the “post-conflict” moment.

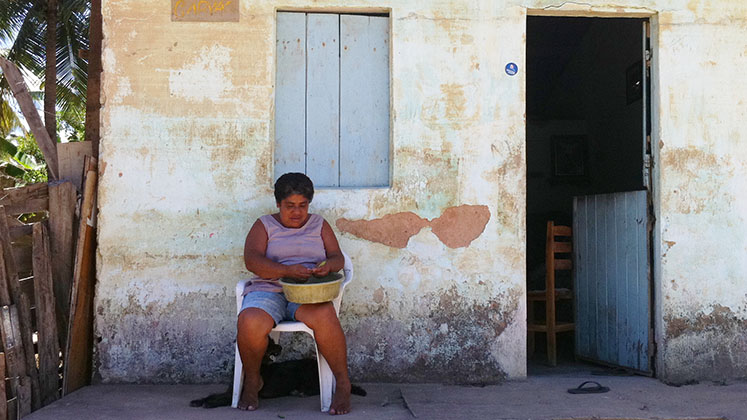

At the same time, slower, more everyday forms of structural violence and exclusion that persist during “peacetime” can also disproportionately affect women in marginalised spaces. Violent spaces outside of conflict zones or conflict moments, such as the urban periphery or rural hinterlands, often shape gender relations in everyday life.

Because of the complexity and context-specificity of violence, there is no silver bullet that can “fix” violence. That said, although different forms of violence can impede women’s ability to access political and civil rights or make claims of citizenship, they can also compel women to develop innovative and highly localised solutions to deal with violence, to muddle through, and to incubate new survival strategies.

Over time, these actions and the ideas underpinning them can coalesce around the mantle of “feminist collective action” as an emergent form of resistance. However, without the means to violence, gendered forms of activism can also place women in dangerous situations as they run up against deeply embedded gender norms and machismo.

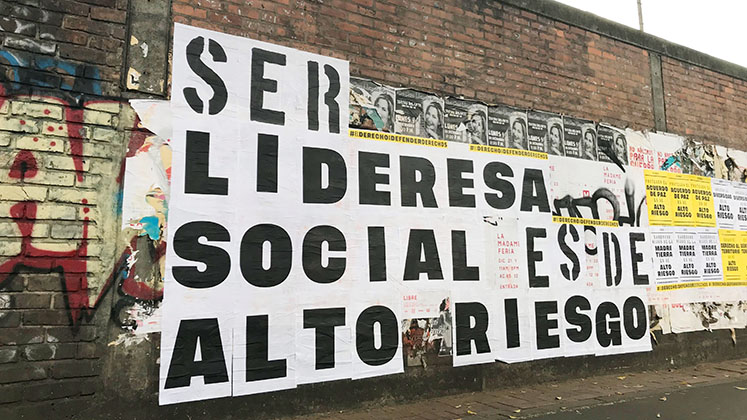

In Colombia, for example, threats, violence, and murders of women social leaders and political candidates have increased at an alarming rate in recent years. Women are being threatened and killed by armed actors for promoting both women’s empowerment and the peace process. In Brazil, the political assassination of city councillor Marielle Franco – a black, bisexual woman from the Maré favela – is testament to the growing threat faced by women who speak out and attempt to tackle imbalances of power.

So how can we make sense of the practices that women employ in these kinds of violent contexts and of the gendered formations of resistance that emerge from them? How do these practices and strategies make sense when they can actually place women in even more danger for (1) daring to contest hegemonic structures and (2) transgressing gender norms in social conditions that are determined by machismo?

Local forms of feminism and constructive social change

Local forms of gendered activism can be highly constructive and productive in violent and insecure contexts.

In Colombia, for example, rural women’s experiences of violence and displacement during the civil conflict brought them together as they attempted to secure basic access to food and shelter. As they communicated and socialised amongst themselves, they developed collective identities that centred on their shared experiences of violence. This crystallised as the notion that “the pain of one is the pain of all” amongst the League of Displaced Women, who came together in the late 1990s.

Similarly, the Alliance of Women Weavers of Life in Putumayo developed localised protection strategies centred on a shared concept of gender justice in order to promote women’s political and economic empowerment during the paramilitary invasion of the 2000s. Having publicly supported the peace process, however, they are now being targeted for their political activism by non-state armed actors (allegedly paramilitary successors).

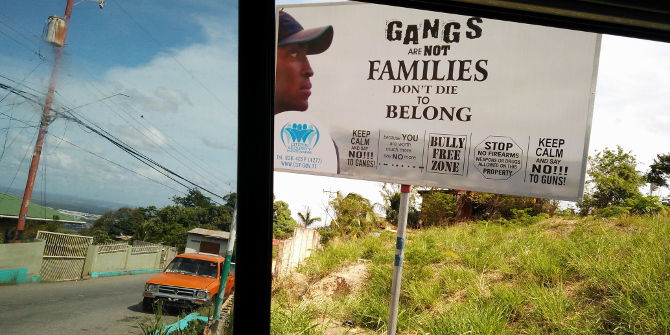

These processes are also visible in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, where women have been disproportionately affected by unfettered urbanisation and male-dominated paramilitary groups. In response, new and emergent acts of resistance and anti-politics have been developed by different female leaders and their community groups. Over time these have matured into more consolidated feminist networks of solidarity, such as the Popular Collective of the Women of the West Zone.

These networks have incubated local forms of resistance that adapt to the conditions of paramilitary domination through projects like community gardens or other “quiet” forms of protest and resistance that take place in women-only spaces. Through such innovative political practices, these women have been able to make collective demands upon the state and local authorities for greater visibility and access to citizenship, a more central role in urban development and planning, and a fairer distribution of resources and wealth.

Consolidating advances in women’s rights

A significant amount of attention, effort, and money is currently being spent by actors at the international level to “correct” gender inequalities. Earlier this month, UN Women even announced that one of the themes of its Generation Equality Forum 2020 will be “feminist movements and leadership”.

Yet many of the projects that have emerged from these gender development programmes in recent years have focused on strengthening institutions, capacity-building, and “correcting” social norms, often with a strong quantitative focus on gender data.

Rather than more of the same, now is the time to take local forms of gendered activism, resistance, and politics more seriously, working to integrate them into these kinds of international forums and events. Just as international organisations need take a more nuanced approach to the advancement of women’s rights by refocusing their funding decisions, policy makers need to reshape their theoretical and evaluative frameworks so that they are working in greater harmony with the specificities of local barriers to achievement of real change.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting