Drawing on his research in Trinidad & Tobago, Belize, and Colombia, Adam Baird argues that only by understanding the multiple roles of masculinites in driving gang formation in Latin America and the Caribbean will we stand a chance of tackling chronic urban violence.

Drawing on his research in Trinidad & Tobago, Belize, and Colombia, Adam Baird argues that only by understanding the multiple roles of masculinites in driving gang formation in Latin America and the Caribbean will we stand a chance of tackling chronic urban violence.

Some might be surprised to hear that 90% of global violent deaths occur outside of war zones. Yet, for those familiar with Latin America and the Caribbean it will come as no surprise that the region is home to the ten most violent cities in the world. The big question is, ‘what can we do about it?’ Despite an increased focus on insecurity, it has proven extremely difficult to turn back the tide of violence and the resulting downward spirals of development.

Violence is actually rather predictable when considered as a socially generated phenomenon. With remarkable consistency it arises in conditions of urban exclusion which become self-perpetuating and enduring, rather like a chronic condition. Young men in poverty represent the group most likely to join gangs, and even a brief glance at homicide statistics shows us that they make up the clear majority of victims and perpetrators of lethal violence. In fact, once you join a gang, your chances of being murdered go up one hundred-fold. Even though most young men do not join up, maras, pandillas, naciones, bandas and combos are so widespread that they can even be understood as a mass rebellion against socio-economic conditions. This points to a crucial question:

How does being a man amidst urban exclusion drive gang membership?

Based on years of research with gang members in Medellín (Colombia), Port of Spain (Trinidad), and Belize City, I propose five possible responses, as well as a way forward:

1.) The masculine logic of the ganging process

The conspicuous consumption and riches, the gangsta glamour of gangs – the partying, drinking, drug-taking, the women, the motorbikes – make them stand out as preferential pathways to a hetero-normative manhood which values strength, womanising, ‘respect’ and power, all against the backdrop of barrio exclusion for young men in Latin American and Caribbean cities. The more sensible question is actually, ‘why wouldn’t you join a gang in these conditions?’

In other words, there is a masculine logic to the ganging process. When contexts of urban exclusion squeeze young men’s ability to become valued men in their communities, they will scour their social world for respectable pathways to manhood. The gang starts to look like a “great opportunity in that situation, the first way out, the first option”, as one young man from a violent area of Medellín told me.

2.) The gang as a tool to contest emasculation

The gang can also serve as a tool for the localised contestation of emasculation – i.e. the incapacity to perform a normatively productive manhood. It becomes a way of being a man, of finding esteem and identity.

I always ask gang members ‘why did you join?’ What stands out from their responses is the pragmatic use of the gang as a reputational and asset-accumulating project. The prospect of being poor and unemployed evokes a deep fear of being looked down upon by the community. As one gang member put it:

You’ve got to be able to support the family, your kid ‘n’ all that so the community doesn’t see you like a tramp, an undesirable who does nothin’, that’s shit. It would be cool to have a good job.

The gang also serves as a vent for youthful ambitions of becoming a ‘successful’ adult, as gangs are often perceived as sites of opportunity where disenfranchised youths can subvert feelings of social subjugation. Joining the gang thus reflects a logical use of agency in settings that restrict legal masculinisation opportunities, though we should always be wary of depicting gangs as grand emancipatory projects given their capacity to entrench local patriarchal gender orders and of course the negative impact of violence and crime.

3.) The gang as an aspirational site

Almost everyone I speak to in poor and violent neighbourhoods can name the local gang leader. Their ‘fame’ – achieved through displays of girls, guns, expensive clothes, and ‘respect’ – are potent symbols and forms of masculine capital, making the gang a standard bearer of male success. Gangs hog the ontological ground, defining the very meaning of barrio masculinity. According to one gang member, “the gang is famous and that inflates your ego… I joined because I was looking for money, luxuries, women”. As we stood on a drug-dealing corner one night looking down on Medellín below, another added, “from up here we’re just like the bourgeoisie”. The gang represents an aspirational site for many young men.

4.) Becoming ‘the baddest’: Why are gangs so violent?

The modus operandi of youth gangs in cities like Medellín revolves around micro-territorial control of drugs sales and extortion, which requires the use of violence. As such, gang members must display a capacity to mete out this violence. One twelve-year-old gang member explained to me that the leader reaches his position by being el más malo, the ‘baddest’, capable of spectacular violence. This means eschewing traces of femininity (at least in public) and not being a loquita, a pussy.

‘Badness’ is a continual process of identity formation and the strategic essentialisation of masculinity: gang leaders are not static, hyper-macho prototypes, but rather they perform badness strategically when necessary, and may equally be loving sons or fathers at home. Violence is operative and emblematic of gangland status allowing young men to come of age. It means “putting on the long trousers… where picking up a gun for the first time gives you power” and metaphorically “sitting on a throne”, as one gang member put it.

5.) Socialisation

Many young men showed agency in joining the gang, whether pulled by ambition or pushed by the desperation of poverty. Others just went with the flow of their peer group, ending up in gangs more unwittingly.

“When we joined we were just kids, stealing a few things now and then, we weren’t an armed group nor nothin’, but from one moment to the next we turned into a gang” said one. Some feel swept into gangs by the sheer weight of violence in their neighbourhoods:

[We’ve] encountered death many times; just by living in this neighbourhood you’re part of the war [and even] the best kids who’ve got everything at home and have other opportunities can end up in the gang.

Whilst reasons for joining the gang were diverse, male socialisation processes were consistently pivotal to gang entry; the importance of friends, family and street contacts, and “getting sucked in little by little” as “the energy of the other person begins to stick to you”.

What can we do about it?

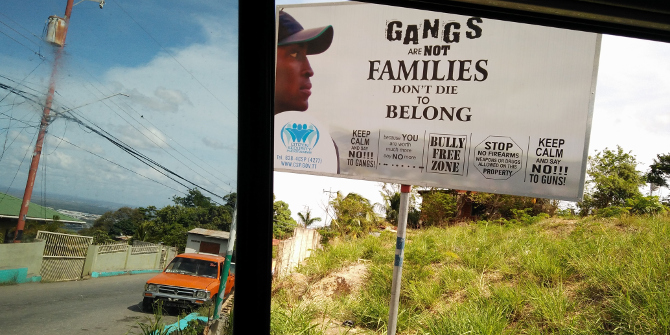

Intervention projects that focus on community violence and masculinities in Latin America and the Caribbean are few and far between. But gang reduction initiatives across the region desperately need masculinities sensitisation to become more effective, which does not mean excluding women. On the contrary, preventing boys from joining gangs requires a holistic approach that includes girls and women in vulnerable communities. This is something myself, Dylan Kerrigan, and Matthew Bishop have recently been working on with the local Roots Foundation and masculinities NGO Promundo in Port of Spain, Trinidad. We are trying to understand how young men ‘break bad’ and turn to violence as drug trafficking intersects with exclusion in the city’s urban margins.

There are still many barriers to overcome. There are very few masculinities-oriented projects, and even less that have been evaluated, whereas any gender focus still tends to be understood as relating solely to women. Moreover, the popular clamour for politicians to ‘do something’ about gangs still tends to prompt hard-line policing tactics that never actually work. There is also a creeping frustration and fatigue at the inability of violence-prevention programmes to deliver clear results and stem the tide of insecurity in the region.

It is up to the academy to develop research excellence that can not only mainstream masculinities into policy but also partner productively with local universities and organisations. If masculinities research can follow the lead of broader gender-mainstreaming approaches, we stand a chance of helping to reduce chronic violence in the cities of the Global South at last.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• This post draws on the author’s recent research article “Becoming the ‘Baddest’: Masculine Trajectories of Gang Violence in Medellín” (Journal of Latin American Studies, 2017)

• Images are not covered by the text’s Creative Commons licence (© 2017 Adam Baird)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Thanks Adam for your thought provoking and illuminative piece.

Your conclusions on the strategic performance of masculinity and how donmanship affords a sense of personhood often denied to low-young men in LA&C really resonate.

Yet, I’m curious though about this term ‘gang’ and how useful it is analytically. It seems an idiom that is often deployed but seldom defined.

Does the term (abd its translation) have a stable meaning across Laventille, Belize city and Medellin?

How might a ‘gang’ differ from a friendship or neighborhood peer group? (And here I’m thinking if Lieber’s study of ‘liming’ peer groups in Port of Spain)

I ask not to be pedantic but just because of how loaded the term is.

Many thanks

A

Hi Adom,

Yes. Good points.

There is no agreed upon definition of ‘the gang’ (although some criminologists may disagree), and in fact, the definitional debates were revisited recently (again) in Decker, S.H. & Pyrooz, D.C., 2015. The Handbook of Gangs, Oxford: John Wiley & Son.

My works relates most closely to what I would call ‘youth street gangs’, to be a little more precise with the language. You might want to look at my recent article cited above ‘Becoming the Baddest’. There I discuss (pp.2-3) some of the challenges associated with these issues: “This points to the complexities associated with gang research and the ‘ganging process’, that is, the process of becoming a gang member. Challenges include transiency of membership, the fluidity of gang–community engagement, a range of interlocution with organised crime and political patronage, and, in the case of Colombia, the galvanising dynamics of the broader armed conflict. This combines to make gang definitions particularly slippery where ‘clear-cut categorisation’ is all but impossible. As such, we might better speak of an incongruous gamut of gangs where a confluence of factors contributes to their emergence.”

Whilst I am weary of defining gangs categorically, it is clear across my research in Belize, Trinidad and Medellín, that the ‘ganging process’ is remarkably similar, but with local cultural nuances. Demographically youth street gangs in these settings are made up of disenfranchised young males. There is much room for comparative research!

In terms of a ‘gang’ versus a youth group just hanging out on the corner, the gang requires some sort of systematic criminal activity. I find it interesting to look at the composition of gangs – you often find ‘hard core’ Dons, Duros, or Big Men, responsible for most violence, then a range of other members, right down to loose affiliates and ‘hangers-on’. So gang membership itself is a fluid nuanced experience.

Hope that was some help.

Best

Adam