Due to the dire experience of its largest city, Guayaquil, Ecuador became an early global symbol of COVID-19’s devastating health effects. But new survey research reveals that the pandemic has also had serious economic, educational, and emotional consequences. Yet even eights month on, serious failings in health and information systems persist, write Katiuska King, Philipp Altmann, and Rafael Polo Bonilla (Universidad Central del Ecuador).

In Ecuador, the COVID-19 pandemic has also been an infodemic, with the crisis being enabled by the spread of inaccurate information and a lack of reliable data to inform decision-making. In order to begin to fill that gap, our research group at the Central University of Ecuador designed and carried out a survey on the social and economic effects of the pandemic for Ecuadorian households.

From May to July 2020, we used mobile phone messaging to implement a nationwide, partially random survey of 2,132 Ecuadorian households. As well as economic data, the survey included questions on emotions, access to information, and political variables that might help to explain why the government’s response failed and what could be done to improve it.

Economic effects of COVID-19 in Ecuador

The data that we gathered reveal a clear economic impact on the population in terms both of paid work and – less visibly – unpaid work.

With regard to paid work, in 37% of households at least one person in salaried employment was affected by changes in their employment situation. The seriousness of these COVID-related changes varied, from reductions in the working day and temporary suspension of contracts right through to loss of employment.

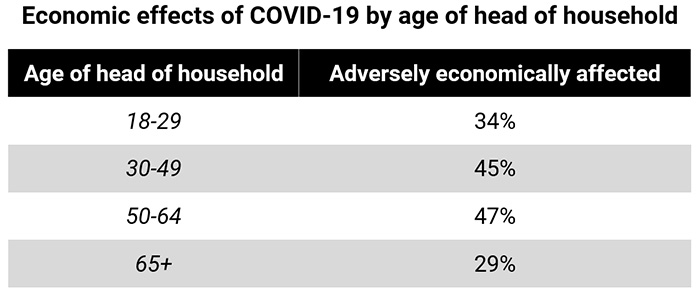

While reductions in hours represented the most common impact, with 47% of households affected, almost a third of households had a member who lost their job altogether (29%). Worse, households whose head was in the pre-retirement age group of 50-64 years were most likely to experience negative economic impacts (see table below). Since this group is likely to have more difficulty in finding new or supplementary employment, this could easily lead to an increase in old-age poverty.

This scenario has clearly been exacerbated by the fact that nearly two thirds of employment in Ecuador is informal (60%) and therefore more vulnerable to instability during an economic contraction. A lack of liquidity only makes this problem worse, yet it is difficult to counteract in Ecuador’s dollarised economy.

Within the household, meanwhile, provision of care has also increased since the beginning of the pandemic. In 48% of cases, care is the responsibility of a single individual, and that individual is far more likely to be a woman.

The COVID-19 crisis and education in Ecuador

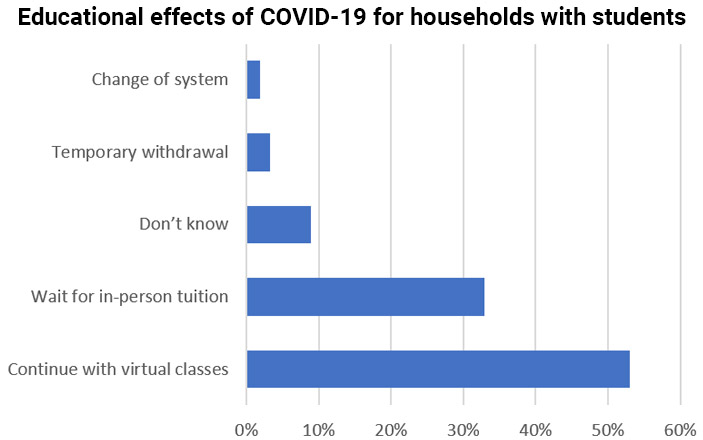

Our study also revealed that the COVID-19 crisis has led to short-term impacts on educational decisions. A small but significant 3% of households containing students (at any level up to university) intended to temporarily withdraw from education altogether, while 2% intended to move students into a different system (from private to public, for example, or to lower-cost private options). More importantly, however, a third of all households (33%) expected to effectively pause education and wait for in-person tuition to restart.

This could set back Ecuador’s recent advances in terms of expanding access to education, which have swelled the ranks of the higher-skilled, university-educated segment of the population. These detrimental effects on education, which are also evident elsewhere in Latin America, can be assumed to be especially grave for households where students constitute the first generation to take up higher education. As with increases in unpaid labour, educational effects are more severe in households headed by women.

Information and Ecuador’s official response

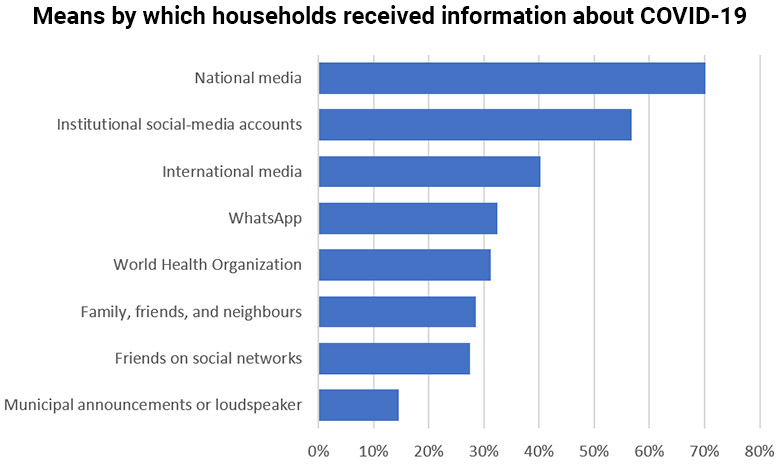

Access to information is another major problem. While 70% of Ecuadorian households get their information from national radio, television, and newspapers, only 20.8% of households believe that these sources are trustworthy. Without access to reliable information, only 39% of the population knows why restrictions were imposed, whereas just 23% know what the basic reproduction number (or R number) is.

Given the widespread lack of a basic understanding of both the pandemic and the state’s response, the public’s lack of enthusiasm in complying with social restrictions is hardly surprising. This lack of knowledge is also strongly correlated with low levels of trust in the government’s management of the crisis, with 82% of households considering the Moreno administration’s response to have been bad or very bad.

Emotional responses to COVID-19 in Ecuador

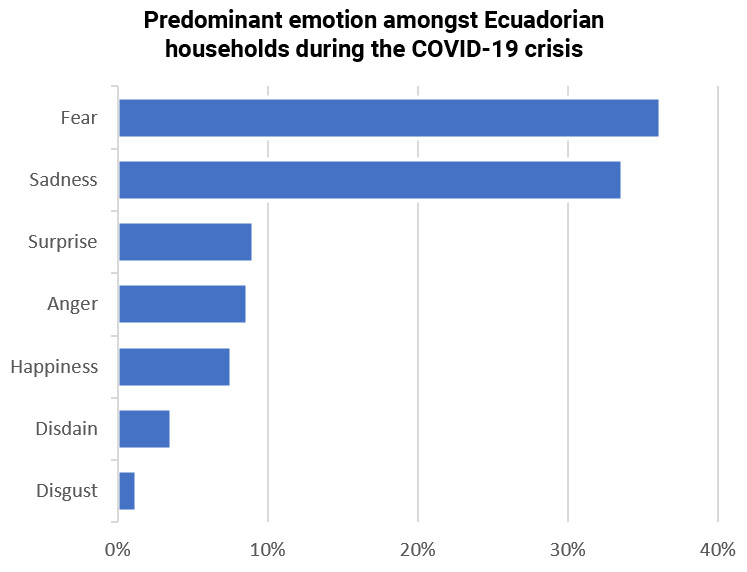

The data also shows that the current situation cannot be seen simply as a collective atmosphere of fear, as many other emotions are present. Predominant amongst them is sadness, largely stemming from the loss of previous routines and “normality”. Although Ecuador also lacks data on mental health impacts, recent reports do show an increase in suicide rates over the last few months.

This climate of prevailing fear and sadness may also have led the government to see this as an opportune moment to pass structural adjustment policies and push for privatisation of public assets.

COVID-19 communication in Ecuador

Ecuador’s attempts to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic have been less effective than those of most other countries in the region. This may relate to the state’s failure to provide testing and extend medical care in the early stages, but this was compounded by a failure to mitigate the social and economic impacts both of the pandemic and of the measures taken in response to it.

The country’s largest city, Guayaquil, became an early symbol of this kind of failure all over the world, with bodies lying in the streets, poor communication about the virus and the response to it, and heavy-handed police violence against rule-breakers. Yet eight months later, both the health system itself and the data-gathering processes for cases and deaths remain largely unchanged.

The lack of clear information also persists, and it is conditioned by media consumption, by education, and by age. In the short run, this needs to be addressed by state actors who have access to the most relevant information, but so far the government has utilised its privileged position to provide post-hoc justifications, last-minute updates, and even misinformation. In the long run, the country would benefit from a more diverse mass media landscape that can hold the government to closer account, enabling the general public to become better informed and more engaged.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• For more information on this study (in Spanish), visit www.covid19uce.com

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Thanks for this. Do you know the effects that C19 had on other treatment protocols like non-invasive (Gamma Knife) cancer therapy ?