Even though different countries responded very differently to the emergence of coronavirus, its impact has been devastating virtually everywhere in Latin America. Underlying factors like labour informality, compounding health issues, low healthcare spending, multi-generational households, and economic openness have made the region’s experience of the crisis especially grave, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

Even though different countries responded very differently to the emergence of coronavirus, its impact has been devastating virtually everywhere in Latin America. Underlying factors like labour informality, compounding health issues, low healthcare spending, multi-generational households, and economic openness have made the region’s experience of the crisis especially grave, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

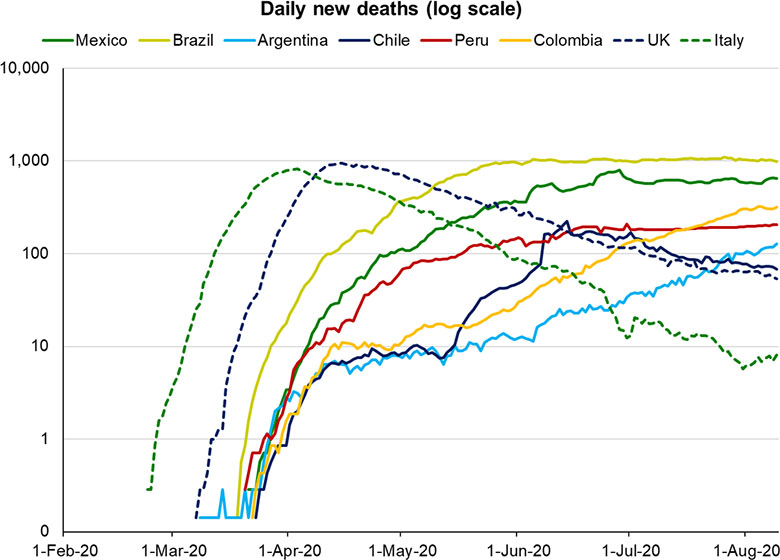

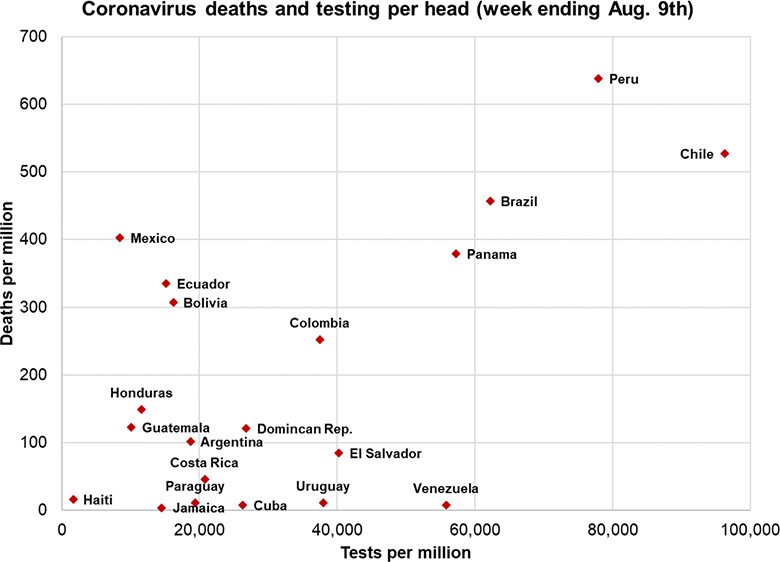

Along with the US, Latin America has emerged as the main battleground in the global fight against COVID-19. Despite the delayed arrival of the virus in the region, Brazil and Mexico now have respectively the second and third highest numbers of total deaths, whereas Peru and Chile are amongst the worst performers in terms deaths per capita. Alarmingly, the infection curves in most of these countries show no sign of being under control. Economic reopening has also proven far more problematic than in Europe, with even an early success story like Costa Rica reporting a spike in cases and deaths since loosening its lockdown in June.

Variations in regional responses

These dismal results come despite a very uneven pattern of responses: indifference and denial in countries like Nicaragua and Brazil versus swift and comprehensive lockdowns in places like Argentina, Chile, and Peru. Many of these responses were undertaken well before European counterparts had acted, and at a point when there were far fewer reported cases and deaths.

Peru, for example, declared a national emergency and began its nationwide lockdown on 16 March, with just 85 cases and no deaths. In stark contrast, the UK had over 6,000 cases and 359 deaths when its lockdown began a week later on 23 March.

Nor have governmental attitudes to the pandemic been the determining factor. Much has been said about the weak responses of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in México, both of whom have appeared to be concerned primarily with the economic impact of lockdowns and their own image and popularity. But in terms of deaths per capita, Brazil and Mexico trail Peru and Chile, both of which mounted far quicker responses, offered more comprehensive economic support to workers, and now boast higher testing rates.

It is worth noting that by virtue of being federal republics, state governments in Mexico and Brazil have had considerable influence on their local pandemic responses. Bolsonaro and López Obrador may have stolen the spotlight due to their irresponsible antics, but the actions taken on the ground by local governments were far more important than many casual observers may have believed.

Was Latin America doomed from the start?

There is a case to be made, however, that the region was always destined to come unstuck when faced with a silently transmitted virus whose co-morbidities are so closely matched to the region’s health profile.

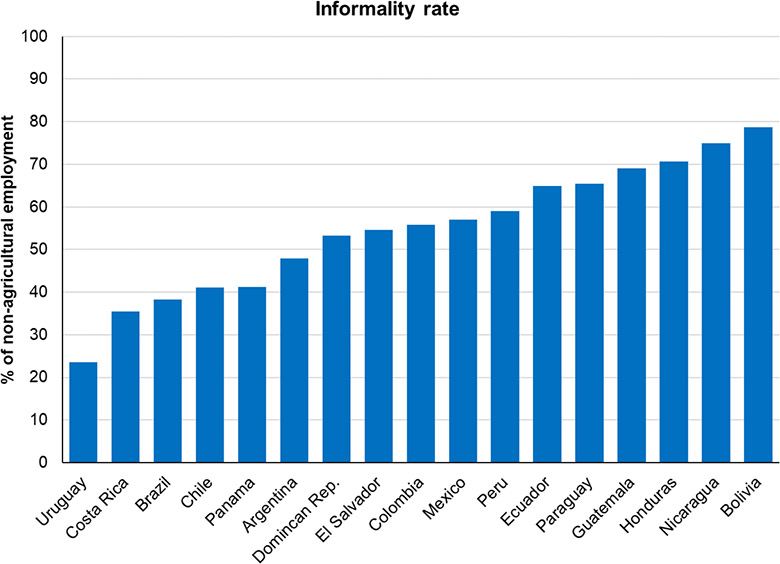

The first weakness, transmission, is directly related to the capacity of regional governments to effectively enforce lockdown, with all the disadvantages that underdevelopment entails. The factor most frequently cited in this regard is the region’s high level of informality, which affects over 40 per cent of the labour force even in wealthier countries like Chile. In poorer countries like Honduras, Nicaragua, and Bolivia, informality exceeds 70 per cent.

Informality complicates lockdown because the general lack of universal social security means that informal workers receive no income support. And since most informal jobs are in hands-on sectors like retail and construction, working from home becomes virtually impossible. Taken together, these two factors make adherence to lockdown rules a literal matter of life and death for millions of people. Governments have been somewhat mindful of this conundrum, which is why many have enforced lockdowns only loosely. But even those workers opting to venture out have found little demand for their wares in near-empty streets.

Even if the region had better resisted the post-1980s ideological disdain for universal social security, governments would have faced other hurdles. Low levels of financialisation mean that millions of Latin Americans lack bank accounts, making it impossible for them to access unemployment support remotely. Fewer still have the means to shop online, so they are obliged to hit the streets to stock up on provisions. Then again, many households even lack refrigerators, which makes stocking up impossible; instead they simply have to make more trips to the shops and buy less on each visit. All of these factors increase the risk of contagion in ways that Westerners have been able to avoid.

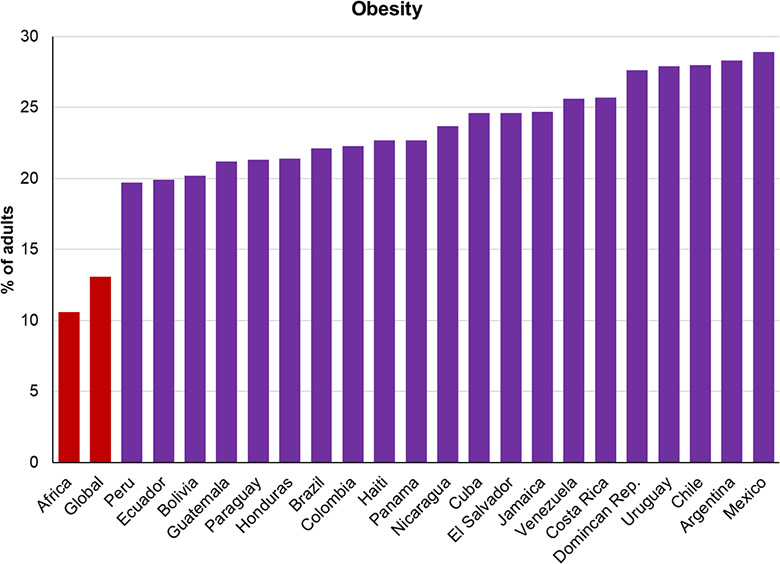

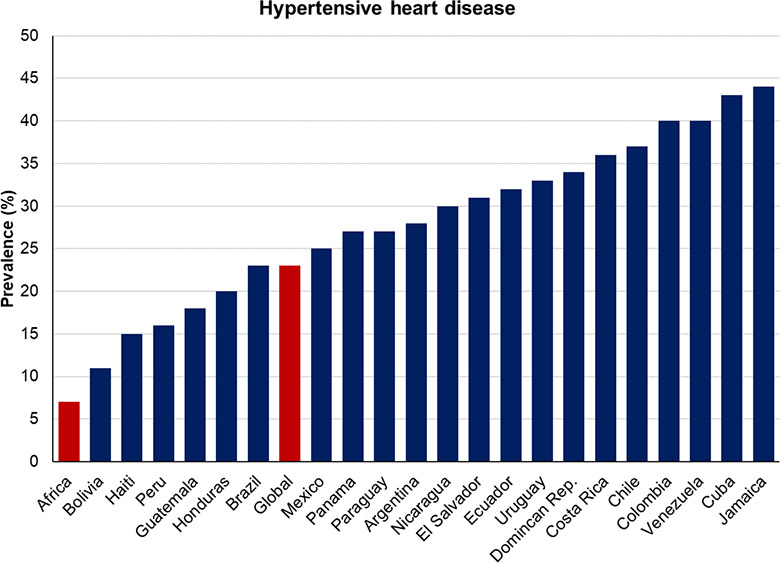

As for co-morbidities, Latin America finds itself in the unenviable position of having third-world incomes with first-world disease profiles. The region has some of the world’s highest rates of obesity (with Mexico second in the world to the US) as well as widespread diabetes and hypertension, all of which have been found to worsen the outcomes of COVID-19. This has also blunted what might otherwise have been the region’s most potent weapon against the disease: youth. Instead, even relatively young people exhibit many of these co-morbidities much earlier than they should, particularly those in their 40s (an otherwise low-risk age group). This potential benefit is further offset by Latin America’s high proportion of multi-generational households, particularly where younger members are forced to work and may inadvertently spread the disease to elderly relatives.

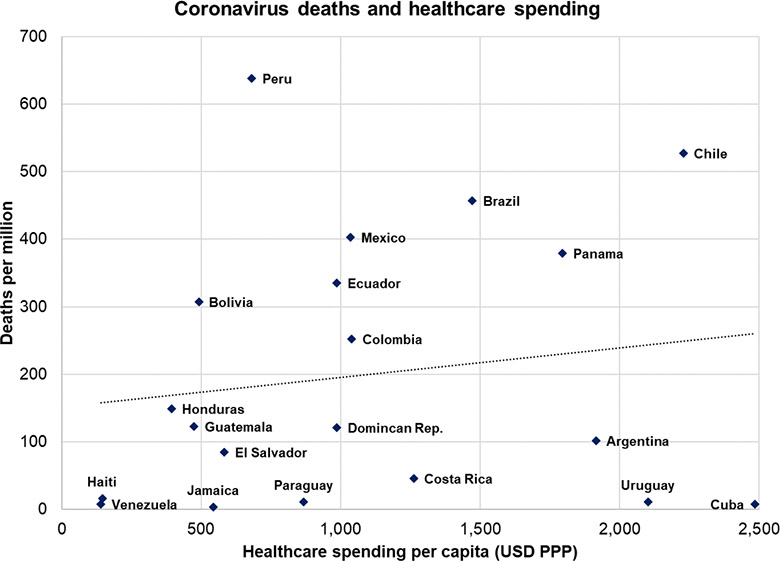

Finally, healthcare spending varies considerably across the region, but even this does not appear to fully explain different outcomes: the region’s top healthcare spenders have not necessarily performed much better than those spending less, whether as a share of GDP or in per capita terms. What is true is that no country in Latin America spends as much as it should, since even in GDP terms not a single country spends as much as the OECD average.

One might point out – notwithstanding the horror stories from Ecuador’s early outbreak and remote Amazonian cities like Manaus (Brazil) or Iquitos (Peru) – that the region has generally managed to avoid the “collapse” of its healthcare systems, but even here there is a caveat. The ability of hospitals to cope is related to the region’s far higher share of deaths occurring outside of hospitals.

Whether because of transportation issues or concerns over the cost or quality of care, many Latin Americans have chosen to avoid going to the hospital despite falling ill. This has undoubtedly led to a higher number of avoidable fatalities. Patients can die from a lack of oxygen even in milder cases that don’t require mechanical ventilation, whereas side-effects like strokes and renal failure can also be fatal outside of a hospital setting. It is estimated that eight out of ten COVID-related deaths in Mexico have occurred outside hospitals, and there is no reason to suspect this would be particularly different elsewhere in Latin America.

Were Latin American economies doomed as well?

The economic fallout from the pandemic is yet another unfortunate consequence of the disease and one that impacts the region disproportionately. According to the IMF’s most recent estimates, Latin America faces the most severe recession of any world region (a contraction of 9.4%), dwarfing its experience even of the 2009 global recession or the 1982 debt crisis.

As with the health crisis, much of this was unavoidable. With their largely open economies and high dependency on tourism, the region’s economies would have been dealt a hammer blow even had there not been a single local case. And though widespread informality does mean that some economic activity slipped through the cracks, this was nowhere near enough to compensate for the effect of lockdowns on the formal sector, which contributes the lion’s share of GDP and fiscal revenues.

Failure to bring down the infection curve has also meant that that Latin America’s lockdowns have been more prolonged. Even where restrictions have been loosened, there is no guarantee that consumers will venture out if the risk of infection is still high. If a second wave hits the Europe over the coming months, it will at least come after a brief economic revival in the summer. Latin America may not see any semblance of normality until a working vaccine is released.

Lessons unlearned

Accepting the premise that the region’s health crisis and economic crisis were largely unavoidable should not be seen as a justification for incompetence. There is no excuse for Bolsonaro’s Trump-like attacks on state governors who were taking the crisis seriously. Mexico’s AMLO was wrong to refuse to follow hygiene rules (except when in the US) and to claim that religious amulets were enough to protect him. Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega should not have buried his head in the sand and disappeared from public view for 34 days at the start of the crisis.

But it does seem that even if these countries had done everything right, the pandemic might not have played out much differently than it has. With so many factors at play, and with so many aspects of the disease still poorly understood by science, there is still no conclusive answer to why some countries have done so poorly despite significant efforts, whereas others have seen similar outcomes while seeming to do much less. That said, it is undeniable that those countries that did well responded early and put the right policies in place. Not all the region’s COVID failings were based on bad policies, but all of its successes were based on good ones.

That a less developed country like Paraguay has done so well is also encouraging because it shows that success action against COVID-19 does not depend on income levels or institutional development alone. It is also true that some of the countries that were hit hardest and earliest, like Chile, are now seeing a reduction in their infection curve, whereas early successes like Argentina and Colombia have seen consistent rises.

But the clearest lessons are for those countries that have struggled from the start. It should now be obvious to Latin America, as for the UK and the US, that taking half-measures or delaying action for fear of the economic consequences ends up being far costlier in the long-run.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

I thoroughly enjoyed the article which the author clearly references to statistics, which enable us to have an open view.

At no point does the author stare that doing something is pointless, indeed he carefully articulates a suggestion.

Open minded and not too heavy, more please.

Although the article contains some interesting comparisons, especially on health issues, I see a number of critical points:

a) Chile did neither react early nor coherently to the crisis but late and ecelectically, article lacks clear indicators for evaluating government policies

b) apart from individual health it is important to include environmental issues like air contamination in major cities

c) cities in Latin America are big – compared with European standards and housing is segregated, mobility is a major issue in transmission (especially for the poor in the peripheries)

d) as Latin America is characterized by high rates of structural inequality, aggregated data say little about concrete conditions (you need to include race/ethnic belonging, class and gender as well)

Despite some nice comparative figures and a few interesting points (e.g. the role of informality), the main message by the author is missleading and worrisome. Both in the abstract and in the last part of the blog, the author argues that “if [Brazil and Mexico] had done everything right, the pandemic might not have played out much differently than it has”. He bases this statement on the outcome observed in countries such as Peru and Chile where, despite better measures (e.g. “far quicker responses, offered more comprehensive economic support to workers, and now boast higher testing rates”), deaths rates are also strikingly high.

Suggesting that even if Brazil and Mexico had taken a different road and implemented “good policies” the outcome would have not chnaged, based on Chile’s and Peru’s experience, is simply wrong. There is no counterfactual of what would had hapenned in Brazil and Mexico and the descriptive analysis in this post is clearly not enough to shed ligh on this issue. Even more worrisome, from a policy making perspective, Rodrigo’s message is a dangerous one. We should be cautious in giving carte blanche to policy makers, particularly during these times and in countries where institutions and counterbalances are not always optimal. I’m looking forward to the sound and robust ex-post empirical analyes that, I’m sure, will be produced to assess the effectiveness of the different response packages implemented worldwide. Meanwhile, I’d be cautious in sending the message “no matter what you do (or don’t do), the impact of the pandemic is given and unavoidable” such as the one given throughout this post.

This is probably one of the best analysis I ever read… specially because is “neutral” in the way that it is an evidence-based OpEd and not just blaming and polarizing as it often happens.

Congratulations, keep inviting the author to collaborate…