With the economic impact of COVID-19 shaping up to be immense and inevitable, Latin America desperately needs to reverse the failures of a development model centred on extraction for export, writes Tobias Franz (SOAS, University of London).

With the economic impact of COVID-19 shaping up to be immense and inevitable, Latin America desperately needs to reverse the failures of a development model centred on extraction for export, writes Tobias Franz (SOAS, University of London).

Aside from its massivee implications for public health, the global COVID-19 pandemic will have serious effects on economic development in Latin America. Even before the outbreak of COVID-19, Latin America’s economy was growing at an annual average rate of less than one per cent per year, making it the slowest growing region in the Global South. Already struggling to recover from the end of the commodity boom and the oil price crash, Latin America now faces the prospect of sliding into a deep economic depression.

The elite politics of low productive capacity

From the 1980s debt crisis, via the global financial crisis of 2007/08, to the slump in global commodity prices since 2015, Latin American economies have long been highly vulnerable to external shocks. The problem is a structural one.

Throughout the twentieth century, most of Latin America failed to industrialise beyond early-stage light manufacturing and into later stages that enable greater productivity growth. The historical domination of political and economic life by landed elites prevented the establishment of a power base that would facilitate industrial accumulation. A lack of competition between different elite factions and the strong position of land-owning classes made it difficult for emerging industrialists to compete over access to state resources. While the dominance of unproductive resource distribution was less problematic during the early stages of industrialisation, it significantly hampered attempts to promote big-push capital-intensive industrialisation.

This inability to develop a productive sector and a deepening dependence on primary-commodity exports and services (often linked to tourism) have left most Latin American economies in a position where minor changes to the global economy have significant ripple effects. This is already visible with the drop in global demand, the collapse of commodity prices, and the near death of international travel that have resulted from the COVID-19 crisis.

This year alone, oil prices contracted by over 50 per cent, and they are now standing at their lowest level since 1973 (US$ 22 per barrel). Coal prices fell by 55 per cent, the tradable value of copper decreased by 21.3 per cent, zinc by 19.4 per cent, lead by 14.6 per cent, and soy beans by 7.7 per cent.

With Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Ecuador, and Venezuela heavily dependent on oil revenues; Colombia being the world’s fifth largest coal exporter; Chile constituting the largest copper exporter; and Peru depending on copper, zinc, and lead exports; the COVID-19 crisis has already had serious detrimental effects on Latin America’s economies.

This longstanding tendency towards export-oriented extractive accumulation over local productive capacity is now demonstrating the structural weaknesses of Latin America’s economies. Entrenched power balances and the dominant position of landed elites are likely to further deepen productivity problems as state provision of emergency loans and stimulus packages could easily favour commodity giants, leaving smaller industrial companies to drift into bankruptcy.

Neoliberalised political economies

This historical failure to climb the productivity and technology ladder has been reinforced since elites in Latin America reversed state-sponsored import substitution industrialisation and started to fundamentally reorganise the institutional configuration of their political economies. The 1980s and 1990s saw an outbreak of what prominent development economist Albert O. Hirschman dubbed “fracasomania” (“failuremania”). This obsession with dismissing everything that went before as a complete failure saw Latin American countries implement a wide range of radical neoliberal reforms.

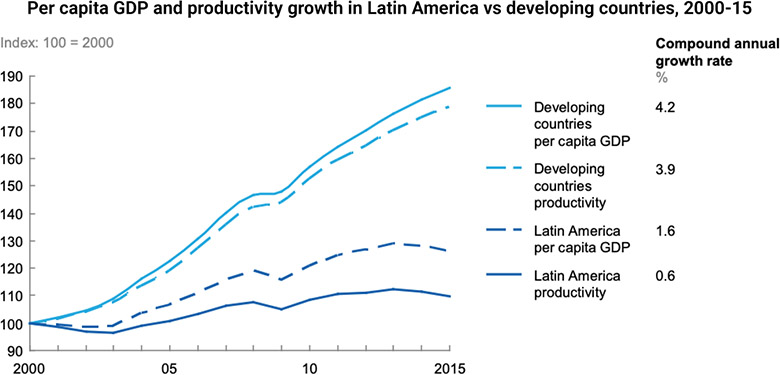

Aside from its effects on public health systems that are today wholly unprepared for the looming COVID-19 health crisis, the quasi-religious adoption of the neoliberal policy paradigm in the 1980s and 1990s also weakened governments’ attempts to diversify their economies. The incapacity of rolled-back states to enforce credible disciplining mechanisms has hindered attempts to compel corporations to invest in strategic sectoral activities, reinforcing low growth of productivity and GDP per capita (as illustrated below).

Elites unwilling to reinvest their profits continue to benefit from Latin American neoliberalism, as they appropriate large profits without fear of withdrawal of government support or deteriorating competitiveness. Irrespective of whether we measure investment as investment per worker, a percentage of profits, or a percentage of GDP, Latin America has extremely low private investment ratios. This has left the region’s firms with little capacity for productivity growth and its economies dominated by low-wage or informal labour.

Liberalisation and integration into transnationalised networks of capitalism worsened this situation. Rather than investing in the generation of domestic content, Latin American elites continue to prioritise the advancement of the system of global finance capitalism from which the vast majority of their income is derived. Elites accumulate large surpluses mainly through moving capital from the real economy into the increasingly sophisticated financial system. Combined with increasing income inequalities and the ever-contracting absorptive capacity of domestic firms in the real economy, this has accentuated problems of underinvestment and weak effective demand.

This deep neoliberalisation of Latin American countries will seriously weaken responses to the COVID-19 crisis and lead to devastating consequences for the population. While debilitated states will struggle to support strategically important businesses, the low-wage and informal labour force will take the hardest hit. With welfare states having been bled dry, workers have nothing to fall back on, no safety net or savings, and no access to quality healthcare. It is Latin America’s poor who will once again be on the sharp end of the neoliberal paradigm.

Financialisation and the explosion of private debt

Another major concern in the COVID-19 crisis is surging corporate debt.

Following the downturn of 2009, Latin American elites leveraged their corporations by borrowing to finance operations rather than reinvesting profits. Financialisation of the economy has facilitated access to cheap credit, allowing unprofitable and uncompetitive firms to survive as asset prices ballooned despite plateauing productivity. Low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE) – an attempt to stimulate economic recovery in the Global North and stabilise international financial markets – resulted in an expansion of debt on the balance sheets of non-bank corporations in Latin America. Using cheap credit made available by QE, speculative investors from the Global North sought refuge in the profitable corporate bonds, equities, shares, and stocks of commodity-producing companies in Latin America. These companies readily accepted this excess liquidity even if it only increased their leverage.

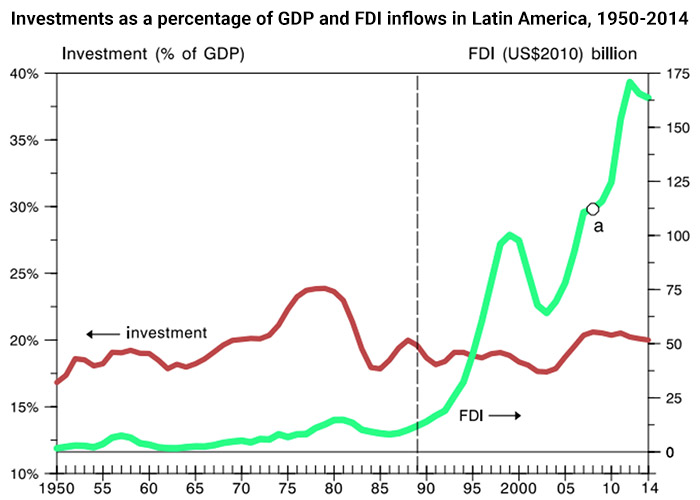

Rather than investing these additional funds into strategic industrial sectors, Latin America’s elites used cheap credit to finance corporate deficits or to move assets into financial markets. As such, the surge in foreign direct investment since QE has had no observable impact on domestic investment rates into the real economy (see below).

Before the COVID-19 crisis, the massive inflow of foreign investments into Latin American economies inflated asset prices and led to a surge of commodity prices. But since the start of the outbreak of the pandemic, investors have been rushing to withdraw funds from Latin America. This has led to a further fall in already collapsing global commodity prices and a sharp decline in asset prices, further imperilling debt sustainability.

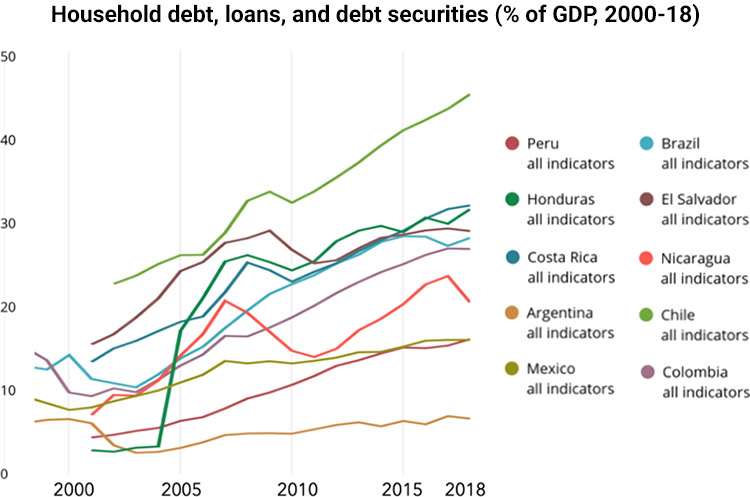

Moreover, and following general trends related to economic financialisation, household debt in Latin America’s largest economies has increased from an average of around 10 per cent of GDP in 2002 to over 25 per cent in 2018 (illustrated below). With wages in the region’s highly flexibilised labour markets being systematically suppressed, households have turned to easy credit in order to finance consumption. Even this increased private debt burden, however, fails to make up for Latin America’s chronic deficiency in effective demand as a result of undervalued, flexibilised labour.

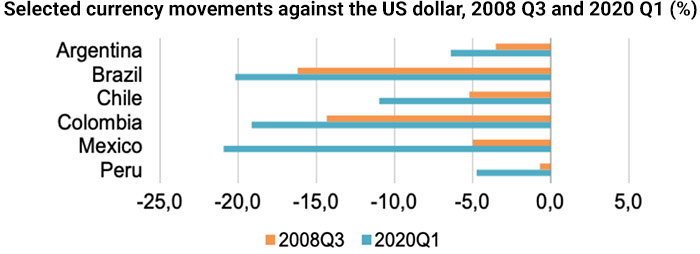

Another aggravating factor for Latin American economies in the current COVID-19 crisis is the structural weakness of local currencies.

The massive influx of liquidity pre-crisis and the inadequate response of central banks has led to appreciation and overvaluation of local currencies. With the outbreak of COVID-19, panicking investors are massively withdrawing funds from Latin America and disinvesting from commodity assets, putting local currencies under extreme pressure. Exchange rates have fallen far lower even than after the financial crisis of 2007/08.

In the last 40 days alone, the Mexican peso has lost 35 per cent of its value against the US dollar, the Brazilian real and the Colombian peso both fell by 24 per cent, whereas the Chilean and Argentinean pesos contracted by 10 per cent and 8 per cent respectively. Given that most private and public debt in the region is held in US dollars, the COVID-19 crisis will seriously worsen an already parlous debt position.

The withdrawal of finance, the collapse of inflated assets, the free fall of exchange rates, the bursting of corporate-bond bubbles, and the uncontrolled indebtedness of corporations and households will have catastrophic consequences – not just for companies in the region but also and especially for poorer individuals and households.

The coming economic costs of COVID-19 in Latin America

Current calculations of the impact of COVID-19 suggest that Latin America’s economies are facing a serious depression. According to the recent Wold Economic Outlook (14 April 2020) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the region’s economy will shrink by an average of 4.2 per cent. This contraction would be even more severe than those experienced during the 1983 debt crisis and the 2009 recession.

- Brazil‘s economy is expected to contract by 5.3%

- Mexico’s reliance on demand from the US (about a third of its GDP comes from exports) will dampen growth prospects significantly, with a contraction of 6.6%

- Argentina’s economy is set to shrink by 5.7%, with the further challenge of having to complete ongoing renegotiation of debts worth US$100 billion

- Colombia’s economy could see a 2.4% contraction

- Chile’s economy is projected to contract by over 4.5%.

- Peru will see an economic contraction of 4.5%

- Central American economies will shrink by an average of 3%

- Economies in the Caribbean will likely contract by 2.8%

As the economic and health crisis deepens and global demand (particularly from China and the US) falls further, these already dire economic projections may need to be revised downward. Latin American economies have to start preparing for a serious depression, as the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis will be catastrophic: an unprecedented decline in trade and commerce, corporations defaulting or going bankrupt due to exploding debt burdens and a credit crunch, sovereign debt crises and further currency devaluations, financial crises resulting from corporate and household defaults on private debts, and a huge jump in unemployment, poverty, and inequality.

Multilateral responses, led by the IMF, have already seen an expansion of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) to support the balance of payments for poor countries. The IMF will also need to create new special drawing rights (SDRs) and transfer existing ones; this will help embattled governments to free up fiscal resources to increase health care funding, to finance key imports, and to address crucial supply bottlenecks.

However, high levels of public and private debt could easily render these efforts futile since additional loans will be used to finance the exploding debt burden. A moratorium on debt servicing is not enough; a crisis of these proportions calls for complete cancellation.

The looming economic crisis can only be addressed if Latin American governments start to radically rethink economic policymaking. The creation of new fiscal resources – perhaps through monetised deficits and monetary financing of government spending where possible – needs to go hand in hand with the reversal of privatisation reforms and the nationalisation of commodity-extracting companies. A shift towards a state-led development model that can make best use of nationalised extractive revenues and newly created fiscal resources is also necessary.

As an immediate response, governments could help to ameliorate the liquidity and solvency problems of households by suspending mortgage and rent payments, creating unconditional cash transfer programmes, and investing in social services in order to mitigate the pressures bearing on those in low-wage or informal employment without access to savings or healthcare. Businesses could be supported by extending loan maturities, deferring taxes, providing credit through central bank finance, and subsidising companies to maintain employment. Equity injections and government guarantees should provide ample liquidity to banks, particularly those lending to small and medium-sized enterprises.

Short- to medium-term monetary and fiscal stimuli would have to be accompanied by longer-term strategies to build up and support strategic manufacturing industries. This would not only break the vicious cycle of low-productivity growth and a low-wage, precarious employment market, it would also begin to tackle the region’s dependency on global demand for commodities.

With the economic impact of COVID-19 shaping up to be both immense and inevitable, the region is in desperate need of a radical reversal of its failed neoliberal, export-oriented development model based on extractive industries and agro-industrial accumulation.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Thanks a lot Tobias for this very detailed and interesting analysis! We are currently working on a documentary about Latin America based on Galeano’s book The Open Veins of Latin America 50th anniversary. Let’s stay in touch and give a shout when you work in Colombia. We are currently in Tenjo, just outside the city.

As a Latin American, I agree with most of the diagnostic presented in the article. No doubt, the almost exclusive reliance in export/extractive/low productivity oriented economies has hampered growth in the region and make it prone to a boom-and-bust cycle. However, the import-subsitution strategy, driven by big-state policy, failed as well in most LatAm countries, or had mixed results. Otherwise, the adoption of neoliberal policies would have been thoroughly rebutted in the 80s and 90s. Low productivity and inefficiency was still the norm, with a pronounced and progressive decay in public services. Thus, I think the article could be superficial in its analysis: why do the “landed” (which in countries such as Mexico, are not) elites avoid investment and prefer other options? Are they intrinsically “evil”? No. The answer is profits, and a structural lack of confidence. In Argentina, a cycle of crises has tought any Argentinean, wether big industrialist or small grocery owner, to invest in buying dollars as soon as possible, to be prepared fot the following bust. The author seems to make a call for states to “compel” investing in “strategic industries”. Well, compelling to do anything has been the name of the game for the last 500 years in the region. Compelling was the name of the game for the XIXc oligarcs; compelling was the philosophy of populist regimes and dictatorships in the XX century, and compelling is the game now. We had enough. Perhaps the answer could be starting to institute things as simple and complex as a democratic rule of law, almost inexistent in the region, and whose abscence benefits the creation of big, compelling, authoritarian, graft-prone elites, being them landed, industrial, or politburos. All systems have failed in LatinAmerica. It’s not the economy…!

Ever since the Monroe Doctrine, Latin America’s potential has been dimmed. To develop properly need aspirational leaders with capacity and freedom to make the necessary changes. East Asia has revealed how that can be achieved.

See:

– Increasing Poverty in a Globalised World: Marshall Plans and Morgenthau Plans as Mechanisms of

Polarisation of World Incomes.

– The dependency school and its aftermath: why Latin America’s critical thinking switched from one type of absolute certainties to another

Do check out Erik Reinert and Michael Hudson.