Dr Nadia Millington reveals the power of culture, ethics and behavioural norms for the development of social enterprises.

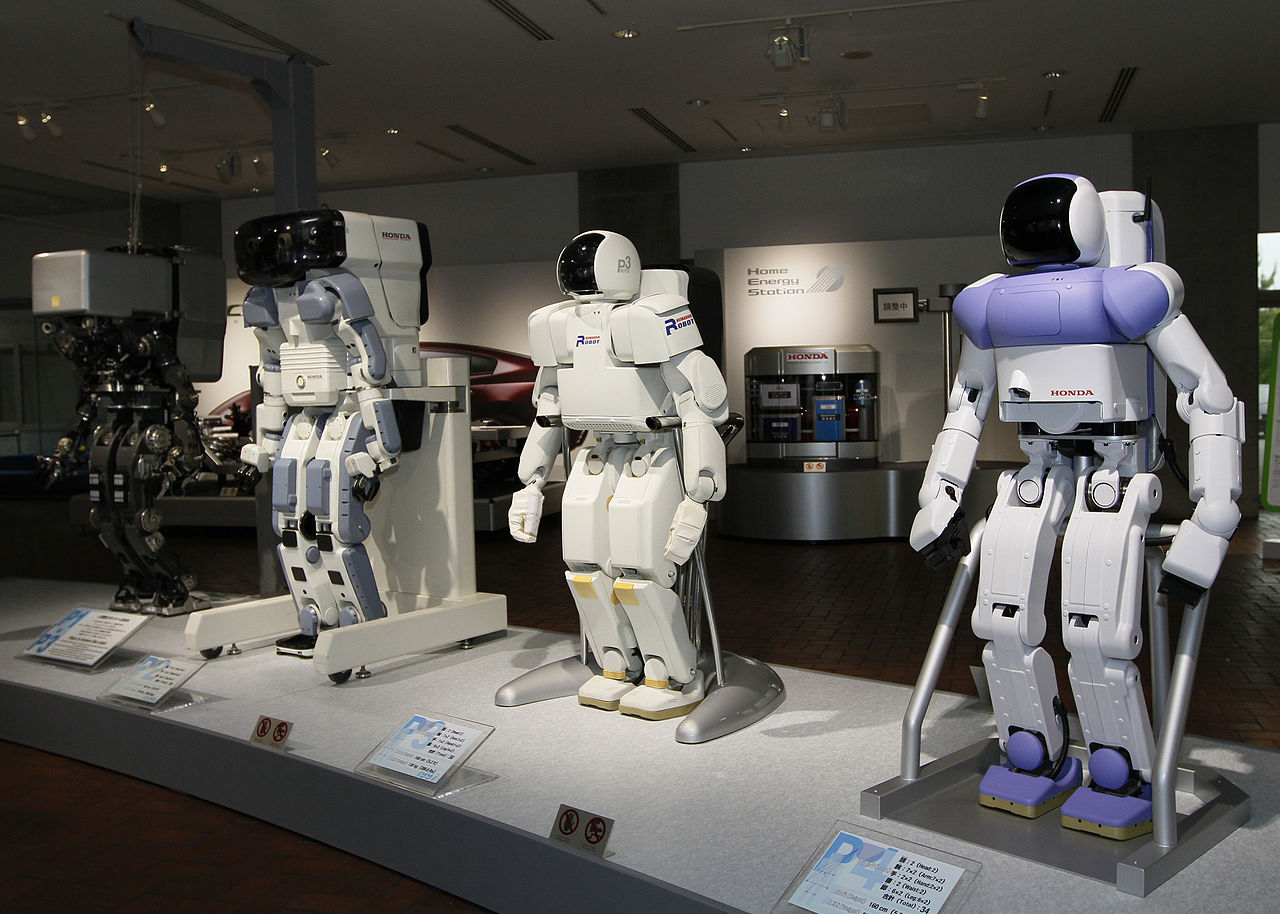

Social entrepreneurship is on the rise in emerging economies. More and more, established firms and start-ups are seeking to position themselves to address the world’s most pressing problems and environmental concerns via enterprise structures that focus equally on commercial and social goals. However, much of the mainstream literature has emphasised management, innovation and investment toolkits at the expense of institutional perspectives. Institutional theories simply propose that market-based activities are significantly influenced by non-market institutional forces that comprise formal institutions – “the rules of the game” – laws, court systems, financial systems and informal institutions – culture, ethics and behavioural norms. Whilst most social entrepreneurs instinctively recognise that formal institutional considerations are important (e.g. financial and regulatory), they often ignore or fail to significantly address the informal institutional forces comprising culture, ethics, and behavioural norms. This can have disastrous effects both with respect to enterprise success and the wellness of the disenfranchised people that they serve.

Take as an example the following vignette told by a formidable African social entrepreneur. In an attempt to address high rates of malnutrition, she produced a low cost yellow natural mango jam but failed to scale because of a predominant behavioural norm of purchasing red jam within that region. Given that behavioural norms are notoriously hard to alter and the yellow mango jam was difficult to reconfigure into a red paste without packing it with sugars and other artificial colours, she opted to discontinue the product, losing the initial investment in product development. On a much larger scale, consider the well documented case of General Electric’s failure to sufficiently address the informal institutional forces of culture and ethics when developing its low cost portable ultrasound machine. Whilst its intention was to improve prenatal healthcare in poverty prone areas, in reality, the machine’s ease of availability and usability, combined with the cultural and deeply rooted historical preferences for male children in India, inadvertently contributed to alarming rates of female feticide and sex-selective abortions. GE later introduced safeguards to try to curtail the use of the machine for sex determination, but the female “gendercide” had already resulted in the progressive skewing of the male to female ratio in places like Punjab, with many negative ensuing social consequences. Truth be told, as an educator in the field, I can site countless other similar examples where lack of explicit recognition of informal institutional forces ( such as norms, culture and ethics) resulted in uninformed responses, premature resource commitments and, in the worst case scenario, deleterious effects on the disenfranchised in emerging economies.