The botched roll-out of government health insurance exchanges has trained a harsh spotlight on the Affordable Care Act. While the health law’s impact on the economy remains sharply disputed, Richard B. Saltman argues that politically motivated implementation decisions – from disruptions of existing insurance coverage to special treatment for labor unions and favored industries – have deepened a legitimacy crisis for government in general. He writes that as levels of citizen trust in government reach an all-time low, the ability of either party to make policy is diminished.

The botched roll-out of government health insurance exchanges has trained a harsh spotlight on the Affordable Care Act. While the health law’s impact on the economy remains sharply disputed, Richard B. Saltman argues that politically motivated implementation decisions – from disruptions of existing insurance coverage to special treatment for labor unions and favored industries – have deepened a legitimacy crisis for government in general. He writes that as levels of citizen trust in government reach an all-time low, the ability of either party to make policy is diminished.

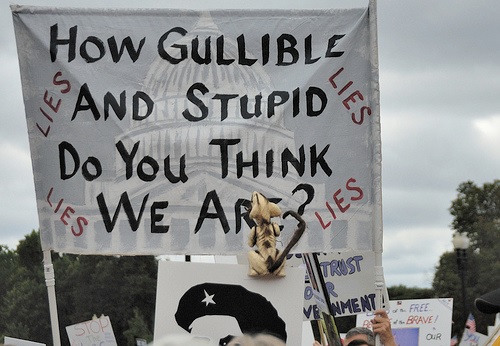

Political scientists like to stress the role of popular legitimacy in the design of good public policy in a well-ordered democracy. Unless a program has broad public support, they suggest, it will be tough to implement and sustain. The lifespan of public policy that isn’t seen as meeting the needs of the broad majority of the citizens can be expected to be, paraphrasing Hobbes, “nasty, brutish and short.” If governments insist on keeping in place policies that citizens don’t see as legitimate, political leaders then have to resort to increasing levels of coercion to maintain compliance, and the risk of corruption grows as various powerful groups try to buy their way out. As governmental behavior in the questioned area deteriorates, popular trust in government in general declines and spreads from bad policies to good. If left unaddressed, the ability of the country’s elected leadership to govern declines precipitously, with the country’s population becoming increasingly distrustful of all political power regardless of which party or leader is in power.

This quick gloss on the core importance of legitimacy in a democracy could be referring, unfortunately, to any recent morning news report in the United States about the problems of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. With this bill, the Obama Administration chose to pursue not just a solution for the 15% of the US population who lacked regular health insurance, but decided at the same time to impose the country’s first official national health policy, directly affecting insurance coverage, costs, and quality of care for the other 85% of the citizenry who already had insurance. Moreover, they set out to transform medical insurance and clinical care in a country which is three-time-zones and a continent wide (excluding Alaska and Hawaii, which are further away still), with a population of 315 million people, nearly 75% of the entire 28 country European Union.

The results were exactly what could have been (and in some quarters were) expected. Without going through the entire litany on the insurance side, the now-functioning insurance exchanges are said by the White House to have produced a small expansion percentage-wise of the Medicaid welfare program—e.g. poor citizens signing up for free care—and a small increase in coverage (perhaps 10%) of those non-poor who lack insurance at some time during the calendar year.

Conversely, however, the 60% of the population who already had private health insurance have been thrown into substantial sometimes extreme disruption in their insurance costs, coverage, and providers. In particular, those citizens in the private individual market who buy their own insurance themselves (some 15 million Americans) found themselves upended both financially and clinically, with policies cancelled outright, initial deductibles on new policies jumping as high as $12,000 a year for a family of four, and long-time treating physicians being excluded from authorized treating networks.

On the employment side, small and mid-sized employers (who provide over 70% of all jobs in the US economy) responded to the higher costs and greater uncertainty of the Affordable Care Act’s myriad mandates and requirements by reducing their exposure. Since the Affordable Care Act required employers with over 50 full-time workers to provide health insurance, small businesses—badly damaged by the post-2008 contraction in the economy, increased taxes, and worried about their own economic survival—and also county and municipal governments responded by a) stopping most hiring, b) reducing or keeping employment below 50 workers, and c) dropping the hours of existing workers back to a maximum of 29 hours a week (the Affordable Care Act stipulated 30 hours/week as full-time). As one direct result, millions of unemployed hourly workers cannot find work and now have dropped out of the workforce entirely, flattering the official but increasingly misleading unemployment rate.

The response of the Obama Administration to these structural problems has been to improvise and delay. Nearly every day now brings a new, major change in health policy, many of them likely illegal under the terms of the federal law that the Obama Administration itself jammed through Congress. Client groups of the administration (labor unions, particular industries like technology) have beaten a path to the White House seeking special dispensation through waivers and special caveats, and, depending on their contributions to Democratic Party fundraising, often getting them approved. The White House, of course, insists that these emergency measures are perfectly normal parts of the implementation process.

In essence, then, in its zeal to provide formal health insurance to the 45 million legal and illegal residents who lacked it, the sitting administration has jeopardized and, in millions of cases, put at risk the existing insurance of 160 million other Americans. Further, as part of this process, the administration has turned health reform into a kind of perverse Middle East bazaar, in which the President grants indulgences from his own signature law to favored supplicants, often based on their prior political contributions to his election.

There remains, of course, a segment of the population who still believe that both this particular expansion of health insurance and the implementation of this new national health policy is a moral imperative. These supporters include the senior leadership of the Democratic Party (re-styled as “progressives”) which controls the US Senate and many state democratic party organizations, many lower income uninsured (many younger uninsured are not impressed), large segments of the Obama-compliant mainstream media, and—tellingly—almost the entire public health and health policy establishment in US universities and think tanks. Thus far, these groups have maintained their conviction in the moral correctness of universal health insurance even as the financial and constitutional consequences of current policy accumulate around their feet.

It has not helped that President Obama, for three years, in every speech, has said “If you like your insurance plan, if you like your doctor, you can keep them.” Especially when documentation from inside the Department of Health and Human Services only recently surfaced showing that the President knew in 2010 that most people would not be able to keep their health insurance, and that most citizens would be forced into “compliant” (read narrowed) networks of doctors and hospitals. Indeed, in a decidedly peculiar live television interview with Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly on Sunday February 2, given as part of the pre-game warm-up to the Super Bowl football game (100 million viewers), President Obama begrudgingly admitted when pressed that he had in fact not told the truth about this issue.

The broader political context in the country has, not surprisingly, exhibited other, equally questionable forms of federal government behavior. These include the National Security Administration (NSA) monitoring of all American emails and telephone calls (despite explicit prohibition in the federal Patriot Act passed after 9/11) and the inaction and deflection of responsibility for the terrorist assault and murder of the US Ambassador to Libya in Benghazi on 9/11 in 2012. Most important, the Internal Revenue Service has been hijacked for Democratic Party political purposes in a manner that not even President Richard Nixon contemplated (Nixon used the IRS to attack political enemies personally, while the targets in the ongoing assaults are political associations participating in state and national elections, thereby fundamentally perverting the democratic process itself).

Drawing the inevitable conclusion, increasing numbers of the electorate no longer trust not just the Obama Administration, but – exactly as political scientists have theorized – they no longer trust government. A Gallup poll of trust in government showed “an all-time low” in September 2013, with only 49% of respondents saying that they had a great deal or fair amount of confidence, “2% below the previous low of 51%.” A January 2014 poll of 6000 college educated adults, conducted annually for a respected private foundation, showed that the percentage of those who “trusted government” had fallen to 37% from 53% in 2013 – a fall of 16% in one year. The rapid rate of decline was particularly worrisome.

What happens next is hard to predict. Financially, the Act is unaffordable in a country that already has piled up $17 trillion or more than 100% of GDP in federal debt (much more if one includes state and local governments), which already has the highest business tax rate in the developed world (35%), and which has unfunded pension and healthcare liabilities that now approach 7 times annual GDP. At the same time that nearly every European country is cutting back social expenditures, however, the Obama health care program continues to blithely spend on. In 2012, the Congressional Budget Office (conservatively) estimated taxpayer costs of $2 trillion more in national debt would be required to pay for the Affordable Care Act’s first 10 years of operation.

Politically, however, the fate of the Obama Administration is too deeply intertwined to extricate either itself or the country from the 2010 Act, and the opposition Republican Party is too feckless to be able to offer a credible alternative either politically or in terms of health reform. Thus the average American has little alternative but to hunker down as best they can, and future measures of trust and legitimacy will in all probability continue to fall.

Thus we come to what is, for President Obama, Democratic Party progressives, mainstream media commentators, and academic health policy elites alike, a thoroughly counter-intuitive outcome. The Democratic Party had expected that expanding publicly subsidized health insurance to millions of Americans would help build a “new coalition of Democrats,” like Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation famously did during the Depression years of the 1930s.

History, however, does not appear to be repeating itself. Instead, even as millions are signing up for coverage, the Affordable Care Act is in practice further eroding the legitimacy of government for a substantial proportion of the American electorate. Far from getting a new electoral coalition, then, the Obama Administration may only be storing up tinder for a far less pleasant political reckoning.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1fNcsI3

_________________________________

Richard B. Saltman – Emory University

Richard B. Saltman – Emory University

Professor Richard B. Saltman is Professor of Health Policy and Management at the Rollins School of Public Health of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. His research focuses on the behavior of European health care systems, particularly in the Nordic Region. He has published 20 books and 130 articles and book chapters on a wide variety of health policy topics, particularly on the structure and behavior of European health care systems.