Immigration has once again become a controversial issue on both sides of the Atlantic, with many concerned about how immigrants integrate into the countries they have moved to. In new research, Monica Boyd and Amanda Couture-Carron examine how the political participation of immigrants in Canada is influenced by their marriage or cohabitation with someone who is native born. They find that foreign born residents with Canadian partners are more political than their counterparts who are married to those who are foreign born, as are their grandchildren. They write that the native born may provide more insight into Canada’s politics and institutions, thus making political participation easier for their partners.

Immigration has once again become a controversial issue on both sides of the Atlantic, with many concerned about how immigrants integrate into the countries they have moved to. In new research, Monica Boyd and Amanda Couture-Carron examine how the political participation of immigrants in Canada is influenced by their marriage or cohabitation with someone who is native born. They find that foreign born residents with Canadian partners are more political than their counterparts who are married to those who are foreign born, as are their grandchildren. They write that the native born may provide more insight into Canada’s politics and institutions, thus making political participation easier for their partners.

From Donald Trump’s scaremongering about Mexicans to concerns about the influx of Syrian refugees into Europe, immigration is again at the top of commentators’ and politicians’ concerns across the world. Many of these questions and concerns revolve around perceptions over the integration of immigrant groups into their host societies. One indicator of integration is whether or not the migrant partners with someone from the settlement country or with someone born there. These types of relationship also are related to other aspects of integration, such as economic and political integration. Studies do document that cross-nativity partnering has positive effects on economic integration; but until now, the links between cross-nativity marriages and cohabitation and political participation have not been examined.

In new research we use survey data to examine how marriages between ‘natives’ and immigrants affect the political participation of their children and the generations that follow. We find that foreign born residents with Canadian-born partners are about as political as third- generation descendants (their grandchildren) who have native-born partners, and that those who are foreign born and have foreign born partners are less likely to vote or participate in politics than their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

In our study, we use data from the Canadian General Social Survey (GSS), to see if cross-nativity marriage is linked to immigrants having similar levels of political participation to the native-born. To measure cross-nativity partnering, for each generation group – the first generation (foreign-born arriving as teenagers or mostly as adults), the 1.5 generation (foreign-born arriving before the age of 15), the second generation (born in the destination country, but with at least one and usually two foreign-born parents), and the third-plus generation (born in the destination country with parents and sometimes earlier generations also born in the destination country), we determine if the respondents have a foreign-born or Canadian-born partner.

We then measure political participation in two ways – voting (or not) in the most recent federal election (for those eligible) and participation in seven political activities within the past 12 months. These activities include: searched for information on a political issue, volunteered for a political party, expressed views on an issue by contacting a newspaper or a politician, signed a petition, boycotted a product or chosen a product for ethical reasons, attended a public meeting, and participated in a demonstration or a march.

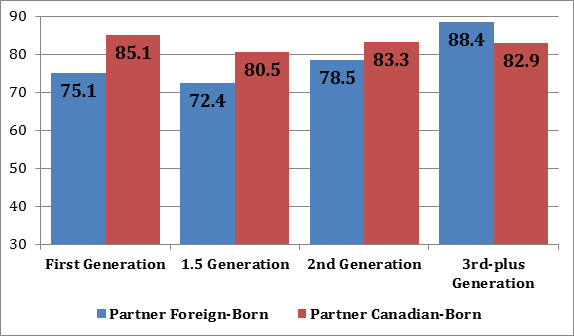

Figure 1 shows the patterns of voting in the most recent federal election in 2006. The first and 1.5 generations with native born partners have a higher likelihood of voting compared to those with foreign born partners. This also is true for the second generation – those born in Canada with Canadian-born partners have a greater likelihood of voting than those with foreign-born partners. Conversely, however, the third-plus generation with Canadian-born partners have lower percentages voting than those with foreign-born partners.

Figure 1 – Percentages Voting in the Last Federal Election by Generation Status & Nativity of Partner, Married or Common-law Population, Age 25-64, Canada 2008

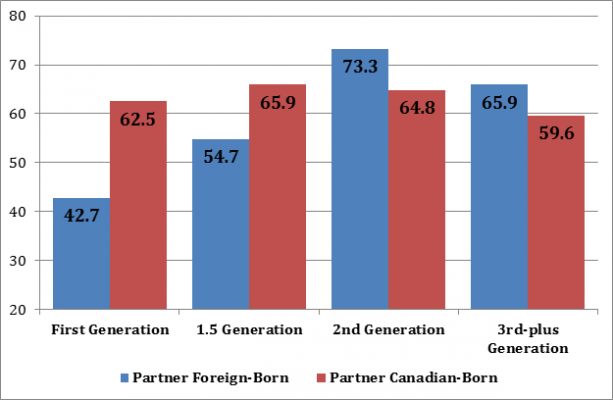

If we look at the percentages who have participated in at least one political activity in the 12 months before the GSS survey, we see the same patterns – except for this measure of political participation, the second generation is more similar to the third generation. For both Canadian-born groups, the percentages engaging in one or more political activity are higher for those who have foreign-born spouses.

Figure 2 – Percentages with One or More Political Activities, by Generation Status & Nativity of Partner, Married or Common-law Population, Age 25-64, Canada 2008

It is possible that generation-specific respondents differ from each other in terms of their socioeconomic characteristics; age, sex, place of residence, and education, and that their partners differ in terms of education, and that generations differ in terms of racial intermarriage and household income. It is likely that these differences are at least partly responsible for these observed patterns, and we take this into account with multivariate statistics.

Our new results indicate what would be observed in comparison to the Canadian-born third generation with Canadian-born partners if everyone in the study were socio-economically similar. Together with our basic results (Figures 1 and 2) these hypothetical results produce four main conclusions:

- Immigrants (both first and 1.5 generation) with Canadian-born partners have similar levels of political participation as the third-plus generation with Canadian-born partners.

- The first generation with foreign-born partners is less likely to vote or participate in political activities than the third-plus generation with Canadian-born partners. These two conclusions hold true even after controlling for variations in group composition (i.e., demographic and socioeconomic differences among the groups).

- While the 1.5 generation with foreign-born partners is also less likely to vote, this group is not less likely to engage in other political activities than the third-plus generation with Canadian-born partners.

- Interestingly, the second generation (regardless of their partners’ nativity status) and the third-generation with foreign-born partners are more likely to participate in political activities than the third-plus generation with Canadian-born partners. This, however, is explained by group differences in demographic and social characteristics rather than cross-nativity marriage.

Our research is the first in the field to use survey data to study the relationship between cross-nativity marriages and political behaviour. Additional research is needed to determine exactly how cross-nativity partnering promotes political integration for the foreign-born partnered with the native-born. But, studies on the relationship between cross-nativity marriages and economic success (usually defined as income or earnings) provide three important insights into possible processes.

First, native-born partners are, in a sense, insiders to the settlement country; they have information on key institutions in the settlement country and they share their insights with their foreign-born partners. For example, some researchers argue that cross-nativity marriage facilitates economic integration because native-born partners are able to provide critical information on the local labour market and provide tools for job searches. We suggest that native-born partners are similarly able to provide insight into the settlement country’s political processes and institutions, which can facilitate participation.

Second, the native-born are also insiders to the settlement country’s norms and customs. As a result, the foreign-born with native-born partners are able to adjust to the settlement country quicker than those partnered with a fellow immigrant. This is key for political integration because a core argument in many studies of immigrant political participation is that exposure to the settlement country’s culture, norms, and institutions promotes political participation.

Finally, research suggests that cross-nativity marriages accelerate immigrants’ attainment of human capital. Studies of economic integration taking this position argue that there is a “spillover” of human capital from the native-born partner to the foreign-born partner. For example, having a native-born partner can help the foreign-born partner learn the language of the settlement country faster, which then impacts earnings and employment rates. If cross-nativity marriage advances immigrants’ destination country language and labour market skills, we also can expect these skills to facilitate political integration since language skills and higher economic status are also associated with political participation.

This article is based on the paper ‘Cross-nativity Partnering and the Political Participation of Immigrant Generations’ in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Featured image credit: Morgan (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1qJll2u

______________________

Monica Boyd – University of Toronto

Monica Boyd – University of Toronto

Monica Boyd holds the Canada Research Chair in Immigration, Inequality and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. She publishes in the areas of gender stratification, ethnic and racial stratification, immigration policy, the labor market integration of immigrants, and the social and economic integration of immigrant offspring.

Amanda Couture-Carron – University of Toronto

Amanda Couture-Carron – University of Toronto

Amanda Couture-Carron is a doctoral student at the University of Toronto with an interest in immigrant integration, specifically in the post migration difficulties of migrants. With her colleagues, Amanda has published in the areas of battered immigrant women and second-generation young adult acculturation stress as well as on these groups’ perceptions and experiences of dating.