Next month, voters in the Peach State’s 6th Congressional District will go to the polls to elect a replacement for Rep. Tom Price, in a contest which many see as an early referendum on President Trump’s agenda. Jamie Monogan argues that this comparison is not accurate: despite Trump’s poor approval ratings, the coming special election is in a safe Republican district, and the electoral rules of its “Jungle Primary” make the contest more about the candidates than the parties.

Next month, voters in the Peach State’s 6th Congressional District will go to the polls to elect a replacement for Rep. Tom Price, in a contest which many see as an early referendum on President Trump’s agenda. Jamie Monogan argues that this comparison is not accurate: despite Trump’s poor approval ratings, the coming special election is in a safe Republican district, and the electoral rules of its “Jungle Primary” make the contest more about the candidates than the parties.

This April, voters in Georgia’s sixth congressional district – located in Atlanta’s northern suburbs – will vote in the first round of a special election to fill a vacant seat in the House of Representatives. This vacancy was created when Republican Representative Tom Price was elevated to the position of Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Trump Administration. Price had to resign this seat to take his new position, so the winner of this election will serve the balance of Price’s two-year term. Many are billing this special election as an early referendum on Donald Trump’s presidency. The dynamics of the race make that comparison inappropriate, though.

Georgia’s “Jungle Primary”

Before explaining why, let’s review the facts because the rules in this special election differ from how Georgians normally elect a member of Congress. In most elections, the Democratic and Republican Parties have a primary election to determine each party’s nominee. Then, in the subsequent general election, voters choose between the Democratic and the Republican candidate. However, this election will use a jungle primary instead. This type of primary is the norm in California, Louisiana, and Washington, but not in the other 47 states.

The jungle primary rules mean:

- All declared candidates from both parties will appear on the same ballot on April 18. Voters may choose from any of the 18 candidates on the ballot.

- In the unlikely event that one of the 18 candidates receives over 50 percent of the vote on April 18, that candidate will be declared the winner immediately and take office in Washington.

- Assuming no candidate attains 50 percent of the vote, the two candidates who received the most votes will advance to a head-to-head runoff on June 20 to determine the winner. This could result in two candidates from the same party advancing to the runoff or a candidate from each party.

So why is it a bad idea to consider this a referendum on Trump? To start, this district, like most congressional districts, is safely partisan. Republicans have represented this district since former House Speaker Newt Gingrich was first elected there in 1978. Democrats who are optimistic about their chances are pointing out that Donald Trump only beat Hillary Clinton in the district by 1.5 percentage points (48.3 percent vs. 46.8 percent). While that is a close margin, it is worth bearing in mind that Trump did, nevertheless, carry the district.

More importantly, coattail effects have a limit in congressional races–particularly since the president is not actually on the ballot. While Trump only barely carried the district in 2016, Tom Price himself performed much better in his reelection bid. Price won by a 23.36 percentage point margin–61.68 percent for Price and 38.32 percent for his Democratic opponent Rodney Stooksbury. Price’s easy win was typical of outcomes in this district. In fact, Stooksbury’s 38.32 percent is the highest vote percentage that any Democratic candidate has earned in this district at any point in the twenty-first century. So the fact that no Democrat has come closer than Stooksbury to winning in this century suggests that a Republican normally would carry the day purely on account of the district’s partisanship. Since this district is not particularly competitive under normal circumstances, it would be unrealistic to expect it to serve as a bellwether of public sentiment on the Republican president.

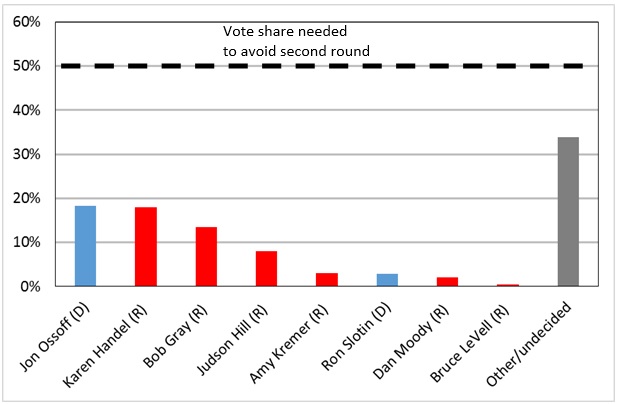

Another reason this race ought not to be considered a Trump referendum is that the different electoral rules make it hard to structure voters’ choice that way. On April 18 voters will choose from 11 Republican candidates, five Democratic candidates, and two independent candidates. Even if a vote for any Republican was considered a pro-Trump vote and any vote for a Democrat or independent was considered an anti-Trump vote, the party totals are not going to be the key factor on April 18. Rather, what is important is which two candidates come out with the highest vote share to advance to the second round: whether that be two Republicans, two Democrats, two independents, or two candidates of differing party affiliation. With 18 candidates in the field, the vote shares are likely to be fractured with even the top two earning rather small vote shares. For example, a recent poll places the top three candidates within five percentage points of each other and no one polling over 20 percent. Figure 1 shows highest-polling candidates, their party affiliations, and their current polling percentages:

Figure 1 – Candidate polling in special election for Georgia’s 6th Congressional District

How Might the Election Play Out?

This tight polling and fracturing of the field implies that there could be a surprise when the top two are chosen. There are two possible situations on April 18. The most likely situation is that one Democrat and one Republican finish in the top two, resulting in a runoff campaign between (most likely) Democrat Jon Ossoff and either Karen Handel or Bob Gray as a Republican candidate. If the Ossoff v. Handel/Gray runoff emerges, it is worth observing that 44.99 percent of voters prefer one of the six Republicans attaining discernible polling numbers, while 20.42 percent of voters prefer one of the two Democrats drawing observable support. While there are many voters who are either undecided or favor one of the other 10 candidates, simply consolidating party support will give the GOP a commanding lead going into the runoff election. Given how safely Republican the district normally votes, a Democrat v. Republican runoff will almost surely result in a Republican win.

The other possibility is that one of the two parties will see its vote fracture more than it currently is, and the other party will take both of the runoff spots. For example, suppose that the above-listed poll numbers described what each candidate was going to garner on election day, but then Ossoff’s support suddenly fractured, with two percentage points of voters each going to Democrats Ragin Edwards, Richard Keatley, and Rebecca Quigg (all candidates lumped into the “other” category in the above poll). That six percentage point swing would drop Ossoff to a third-place 12.31 percent, which would result in a Handel v. Gray all-Republican runoff. If that happened, then the GOP could celebrate retaining the seat before the runoff even happened.

While it may be an uphill battle, the Democrats’ best hope at flipping the seat would actually be to try to sneak both Jon Ossoff and Ron Slotin into the top two. The strategy for this would be threefold:

- Convince the three lowest-polling Democrats (Edwards, Keatley, and Quigg) to drop out. Already, with fewer candidates than the Republicans, there are fewer places for Democratic votes to fracture. The fewer candidates either party has, the easier it is to consolidate the vote and push a candidate into the top two.

- Push Slotin’s candidacy among undecided voters, in hopes of driving-up his numbers without hurting Ossoff.

- Campaign hard for some of the least popular Republican candidates (those polling less than 1 percent) with negative ads against Handel and Gray in hopes of fracturing their vote more. The easiest way for this to happen would be with a SuperPAC-funded ad campaign, though parties and candidates are prohibited from coordinating with SuperPACs.

If the Democrats managed to swing that three-part plan, it would be an impressive execution of strategy. If that does not work, though, all the Republicans really need in order to retain the seat is for one candidate to make it to the runoff. Then, voters’ partisanship will carry the Republican candidate the rest of the way. In the meantime, the only question is which party can better manage the chaos of the jungle primary. Certainly, a seat in the House of Representatives is quite value valuable in its own right, so electoral strategy is important for that reason. Yet, a question of who can best navigate electoral rules is hardly a referendum on the president.

Featured image: I’m a Georgia Voter by Paul Sableman is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2mNugiA

_________________________________

Jamie Monogan – University of Georgia

Jamie Monogan – University of Georgia

Jamie Monogan is an assistant professor at the University of Georgia, where he studies political methodology and American politics.