The US federal system of government historically allowed America’s political parties and governance to be decentralized at the state and often local levels. Timothy Conlan writes that several trends in recent decades have worked to undermine that decentralization. Now, he argues that the rise of nationalization and polarization, and the declining perceived legitimacy of the federal government, means that politics are increasingly national, partisan, and suffering from declining trust.

The US federal system of government historically allowed America’s political parties and governance to be decentralized at the state and often local levels. Timothy Conlan writes that several trends in recent decades have worked to undermine that decentralization. Now, he argues that the rise of nationalization and polarization, and the declining perceived legitimacy of the federal government, means that politics are increasingly national, partisan, and suffering from declining trust.

Received wisdom once held that the decentralized character of American federalism was a reflection of, and largely sustained by, a decentralized political system. But three powerful trends—nationalization, polarization, and delegitimation— now require a rethinking of the relationship between politics and federalism, from elections to policy making to administration.

Nationalization

Historically, American political parties were highly decentralized, organized primarily at the state and local levels. The decentralized structure of American parties was so prominent that many argued that it was responsible for the degree of decentralization in the US federal system.

Since the 1960s, however, both the political and intergovernmental systems have become more nationalized. State and local party systems declined with the erosion of patronage politics, the growing openness of party nomination processes, and changes in party rules and campaign finance laws. At the same time, the national party organizations grew much stronger in terms of fundraising, staffing, candidate recruiting, and the provision of campaign services to candidates for national and state office. Citizens increasingly vote straight party tickets at all levels of government, outside money flows in to crucial state and congressional elections, and candidates, activists and voters are increasingly energized by national concerns.

All of this has implications for intergovernmental policy making. Democratic Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill, once famously quipped that, in Congress, “all politics is local.” Members of Congress in O’Neill’s day routinely resisted entreaties by presidents and party leaders in order to pay homage to the local political leaders, interests, and concerns that got them elected to Congress. Locally driven electoral incentives biased the federal aid system towards narrow categorical grants, and many sensitive national programs—such as welfare and unemployment insurance—were left to state administration.

Such local influences still exist in legislative politics, but the vast majority of Members now vote along partisan lines on most important roll call votes in Congress, regardless of local economic effects. Members of Congress perceive that their electoral fates are tied to those of their party at large, leading prominent scholars to suggest that today “all politics is national.”

Certainly, the propensity of Congress to enact federal mandates and preemptions restricting the autonomy of state and local governments rose in concert with the declining power of state and local party organizations in the 1960s and 1970s. As politics, campaigns, and communications have become more nationalized, more intrusive federal policies have been adopted in the most traditional of state and local responsibilities: education, law enforcement, and fire protection. Early proposals by the Trump Administration that threaten financial sanctions on so-called “sanctuary cities” and that make preemptive changes in the federal tax code indicate that this trend is likely to continue.

Polarization

Partisan polarization has become a dominant feature of American politics. It is increasingly pervasive among citizens, politicians, and the media. While much attention has been paid to its impact on elections and the workings of Congress, less attention has focused on its implications for federalism. Increasingly, partisan polarization is affecting the design and implementation of federal programs in the states, as well as the policy initiatives and operations of state governments themselves.

Credit: Princeton University Digital Library.

High levels of partisan polarization in Congress have important intergovernmental policy implications. Under conditions of divided party government, it often leads to gridlock and stalemate. But when presidents are elected with majorities in each house of Congress, as in the case of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, they are often able to secure impressive intergovernmental policy victories, such as No Child Left Behind and the Affordable Care Act.

Such expressions of conditional party government are not confined to Washington. Geographic polarization means that many states now have unified party governments—something much more common today than twenty years ago—which has allowed them to pass a breathtaking array of novel policies, from limitations on abortion, welfare benefits, and public unions in conservative states to green energy initiatives, minimum wage hikes, and criminal justice reforms in many blue states. It also poses severe challenges for the intergovernmental lobby. Forty five years ago, the nation’s mayors and governors were among the strongest interest groups in Washington. They joined with the Nixon administration in the early 1970s to muscle General Revenue Sharing through a deeply skeptical Congress. They blocked plans to phase out federal welfare programs under the Reagan administration, and they won passage of a state-friendly version of welfare reform in the mid-1990s.

Today, however, unity among the intergovernmental lobby has grown increasingly rare, and its influence has declined. In a highly polarized era, local government groups—whose members lean heavily Democratic–have little influence with a Republican Congress, while the National Governors Association (NGA) is riven by partisan divisions. These divisions prevent the consensus oriented NGA from taking positions on many critical issues of intergovernmental policy. Authority and influence ceded by paralysis of the NGA has leaked increasingly to the highly partisan Republican and Democratic Governors Associations, or left to the scramble of every state for itself.

Polarization and Administration: Polarized federalism is intruding into public administration, as well. The established model of technocratic, “picket fence” federalism is being challenged by a new model of vertical partisan polarization. Functionally oriented, picket fence federalism provided the traditional administrative framework for intergovernmental cooperation. Professionals with shared priorities and normative frameworks often find they have more in common with colleagues at other levels of government than with elected officials in their own jurisdiction.

This technocratic system has increasingly come under challenge. Beginning with the Recovery Act in 2009, many Republican governors and state legislatures began to refuse federal assistance at rates far higher than in the past, often for explicitly political or ideological reasons. Several governors turned down additional federal funds for extending unemployment insurance benefits, while others rejected millions of dollars for developing high speed rail networks.

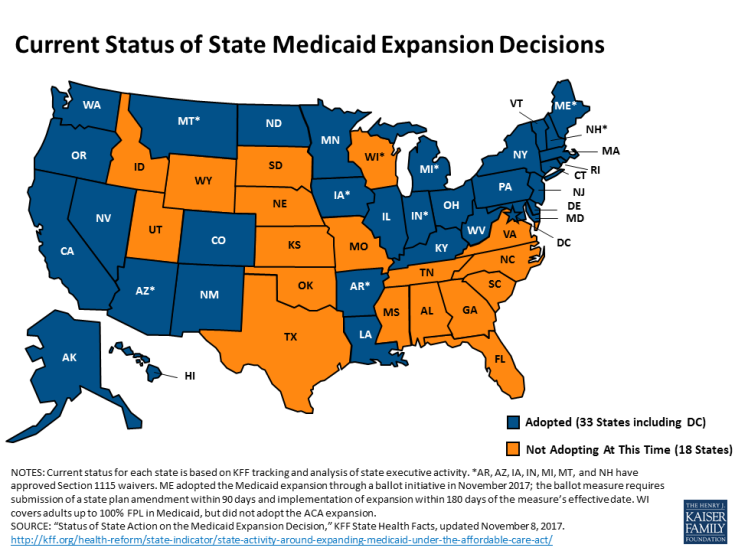

A similar pattern emerged during implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Polarized push back first appeared when twenty six Republican state Attorneys General sought to have the law declared unconstitutional. They won a partial victory from the Supreme Court when the mandatory expansion of Medicaid was held to be unconstitutionally coercive.

Once this occurred, states could elect whether or not to participate in the expansion of Medicaid, as well as in the creation of state insurance exchanges. The result has been a patchwork of state implementation of health care reform, shaped largely by partisan tensions between the federal and state governments. As Figure 1 shows, as of January 2017, only 32 states and had elected to expand Medicaid coverage, including seven mostly Republican states that did so under special Medicaid waivers that allow them greater flexibility. Nineteen states still refuse to expand coverage. A similar patchwork characterizes state participation in the health insurance exchanges.

Figure 1

This pattern of vertical polarization continues under President Trump, although the partisan roles between Washington and the states are reversed. Across a range of issues—from the travel ban to climate change to sanctuary cities– Democratic leaders at the state and local levels have mobilized to fight, block, or ignore initiatives from the Trump Administration. The processes of vertical polarization within the intergovernmental system continue unabated.

Delegitimation

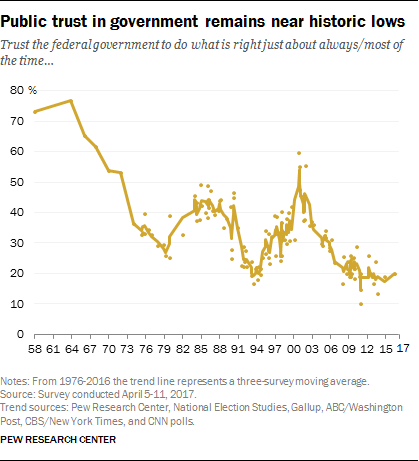

A third long-term trend with implications for the politics of American federalism is the slow decline in the perceived legitimacy of the national government. Public loss of confidence is one key indicator of delegitimation, and there has been a sizable and continuing erosion in public confidence towards the federal government. Whereas over two-thirds of the population said they trusted the federal government to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time” in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as Figure 3 illustrates, only about twenty percent of the population expressed high levels of trust in the federal government in 2017. Some elements of the federal government—particularly Congress–have fared even worse.

Figure 2

Source

Trust in state and local governments has remained higher and more consistent. According to Gallup, sixty three percent of respondents said that they had a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in their own state government in 1972; sixty two percent said the same in 2014. Local governments have fared even better, with 71 percent of citizens expressing a great deal or fair amount of trust in their local community in 2016. Such levels of confidence in local government have been remarkably consistent in Gallup’s surveys, never falling below 63 percent since 1972. Similar results can be found in other survey questions.

Delegitimation and Public Policy: Although there are a number of reasons why confidence in the national government has diminished since the early 1960s, one significant implication for federalism has been increased impetus for Washington to rely on “government by proxy.” Rather than rely on classic techniques of direct service provision by government employees, the federal government increasingly has turned to intermediaries and the tools of indirect or third party governance: grants-in-aid, tax expenditures, loans and loan guarantees, private and non-profit contractors, and entitlement programs. Combined, these make up the greater share of the federal budget (or, in the case of tax expenditures, over $1 trillion in revenues foregone) and employ far more people outside of the federal government than within it.

Reliance on indirect policy instruments and third party governance has deep roots in American history and political culture. But contemporary delegitimation reinforces this predilection and contributes new energy to the trend toward third party governance. Policy makers, seeking to respond to public demands for services but sensitive to public distrust of the federal government and its bureaucracy, have found that techniques of indirect government provide a temping solution to the paradox. Suzanne Mettler notes, however, that this can create a reinforcing cycle of distrust. Suspicion of the federal government, combined with greater trust in state and local governments, encourages Congress to rely on the tools of indirect government. But the resultant “submerged state” reinforces public suspicions about the national government and contributes to a downward cycle of cynicism and dissatisfaction.

- This article is based on the paper “The Changing Politics of American Federalism” in State and Local Government Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2B4BuIX

_________________________________________

About the author

Timothy J. Conlan – George Mason University

Timothy J. Conlan – George Mason University

Timothy J. Conlan is University Professor of Government and Public Policy at George Mason University. He is the author most recently of Governing Under Stress: The Implementation of Obama’s Economic Stimulus Program (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2017).