Neighborhood resources – and areas with limited access to fresh produce (‘food deserts’) in particular – are important forms of inequality associated with the health outcomes of neighborhood residents. Applying ‘minority competition’ theory to neighborhood resource disparities, Jarrett Thibodeaux finds that the percentage of African Americans in a U.S. city predicts the placement of supermarkets near African Americans within the city. Other neighborhood resource disparities suffered by racial minorities may be caused by the ‘perceived threat to resources’ that a growing racial minority can provoke in the racial majority.

Neighborhood resources – and areas with limited access to fresh produce (‘food deserts’) in particular – are important forms of inequality associated with the health outcomes of neighborhood residents. Applying ‘minority competition’ theory to neighborhood resource disparities, Jarrett Thibodeaux finds that the percentage of African Americans in a U.S. city predicts the placement of supermarkets near African Americans within the city. Other neighborhood resource disparities suffered by racial minorities may be caused by the ‘perceived threat to resources’ that a growing racial minority can provoke in the racial majority.

Studies of ‘neighborhood effects’ have shown that the characteristics of neighborhoods independently influence the lives of neighborhood residents (e.g. social networks, health, victimization, etc). The resources that exist (or do not exist) within a neighborhood is one way individuals can be affected by their location. These neighborhood resources could include street renovations, school funding, fire departments or, as focused on here, needed retail establishments such as supermarkets.

Supermarkets are an important neighborhood resource. Being one of the largest employers in the U.S., supermarket locations affect the job prospects of nearby residents. Supermarkets also provide public spaces for the maintenance of informal social ties and, similar to other signs of disorder, lacking supermarkets may help to stigmatize a neighborhood. Currently, the most discussed problem resulting from a lack of supermarkets is the effect on health. Known colloquially as the ‘food desert’ literature, a large body of research has shown that residents of ‘food deserts’ – areas where people do not have easy access to healthy, fresh foods – tend to have worse health outcomes including higher rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Previous research on supermarket location has shown that supermarkets are more common in central city locations and less common in areas with higher rates of poverty and a higher proportion of African Americans. This research tends to assume or imply that neighborhood demographics are the cause of supermarket locations. Similarly, policy makers tend to assume that in order to attract supermarkets to underserved areas one must either change the areas’ demographics or artificially alter the negative consequences of these demographics on supermarket profits.

The dynamics of the city in which a neighborhood resides provides an opportunity to understand the broader causes of the relationship between neighborhood demographics and supermarket location. In 2006 Mario Small and Monica McDermott presented a ‘conditional perspective’ of organization placement patterns, arguing that the relationship between neighborhood demographics and organization location depends on the characteristics of the city. Using 2000 national data, they showed that the zip code placement patterns of 10 organizations (including supermarkets) in relation to the rate of poverty of the zip code depends on which region of the U.S. the city is in and the poverty rate of the city as a whole.

In new research I extend this ‘conditional perspective’ using ‘minority competition theory’ to help explain why supermarkets tend to avoid zip codes with higher percentages of African Americans. Perhaps known more widely as ‘racial threat theory’, minority competition theory is a way to describe how macro level processes affect motivations to discriminate which, in turn, affects racial inequalities. Research on minority competition has typically focused on the affect of the percentage of minorities on punishment practices; Research utilizing this theory has found that increases in the percentage of minorities relates to such phenomena as support for punitive policies, interracial killings, high school punitiveness and disenfranchisement. Along with explaining punishment patterns, minority competition can also prove useful when explaining neighborhood resource disparities.

In terms of neighborhood resources, minority competition theory can be thought of as a three part process. First, the (racial) majority gives little attention to minorities when their population is small; however, as the minority population grows, the majority will increasingly perceive this minority as a threat to neighborhood resources. Second, as the majority perceives the minority as more and more of a threat to neighborhood resources, they will increasingly use discriminatory means to push these resources away from minorities (though this increased discrimination is cumulative, in that an increase from 5 percent to 10 percent minority will provoke more discrimination than an increase from 20 percent to 25 percent). Third, the increased discrimination that pushes neighborhood resources away from minorities leads to greater disparities in neighborhood resources.

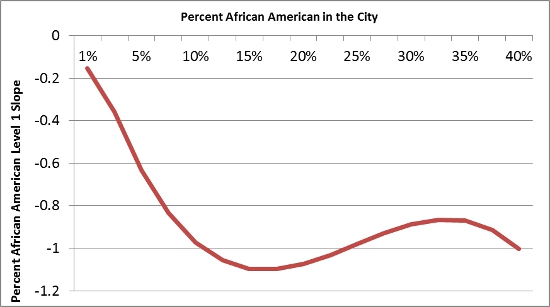

Using 2010 U.S. national data with a zip code within metropolitan statistical area (MSA’s) data structure (16690 zip codes nested within 366 MSAs), I find that the relationship (shown in Figure 1) between the percentage of African Americans and the number of supermarkets in a zip code depends on the percentage of African Americans in the MSA as a whole.

Figure 1 – Relationship between number of supermarkets and percentage of African Americans in MSA

Interpreted in terms of minority competition theory, the graph suggests that at low levels of African Americans in a city there is low perceived threat and low inequality in the placement of supermarkets. As the percentage of African Americans in the city increases, supermarkets are increasingly located away from African Americans; However, at high levels of African Americans in a city, the increasing unequal distribution of supermarkets away from African Americans declines – theoretically due to the cumulative effect of discrimination (along with an increased ability to somewhat attenuate discrimination when numbers are high).

These results indicate that, at least for supermarkets, minority competition theory can prove useful in explaining how city ‘minority competition’ dynamics can push neighborhood resources away from African Americans. Future policies attempting to attract neighborhood resource near African Americans may do well to examine anti-discrimination tactics (though future research will be needed to show exactly how discrimination is occurring). But, more generally, instead of attempting to change the demographics of a neighborhood (which has many times led to gentrification) future research and policy should examine the city dynamics that foster neighborhood resource disparities.

Featured image credit: Roadsidepictures (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1P6kdfi

_________________________________________

Jarrett Thibodeaux – Framingham State University

Jarrett Thibodeaux – Framingham State University

Jarrett Thibodeaux is a Temporary Assistant Professor of Sociology at Framingham State University. His current research focuses on the city and industry causes of, and possible solutions to, neighborhood resources disparities (with an emphasis on ‘food deserts’). His substantive areas of expertise include Crime, Law & Deviance, Economic Sociology, Public Health, Social Problems, Social Theory, Urban Sociology and Urban Studies.

Racial discrimination is a still a major factor in the USA, not politically perhaps but certainly economically. Blacks are still the poorest minority not so much because they have little to contribute economically but they have little access to the opportunities they would need to succeed. This then leads to a vicious cycle of sorts because then their neighborhoods become prone to all the vices such as crime, drugs, etc. Which makes these neighborhoods “unattractive” for business.

This article and similar research make such blanket statements problematic.

For example, data show that in one city economically disadvantaged areas are undeserved by supermarkets in some cities (e.g. Small and McDermott, 2006) and at one period of time (e.g. Thibodeaux, 2016) but not in others. This featured article shows that the presence of supermarkets is limited in African American zip codes (controlling for zip code economics) in *some* cities but not others.

A major point in all of this is that neighborhoods themselves (being economically disadvantaged or high proportion racial minority) do not *necessarily* lead to certain outcomes; rather city and industry factors – in this case city ‘racial threat’ dynamics – come down to affect the outcomes of these neighborhoods.

-Small, M. L., & McDermott, M. (2006). The presence of organizational resources in poor urban neighborhoods: An analysis of average and contextual effects. Social Forces, 84(3), 1697-1724.

-Thibodeaux, J. (2016). A Historical Era of Food Deserts Changes in the Correlates of Urban Supermarket Location, 1970–1990. Social Currents, 3(2), 186-203.