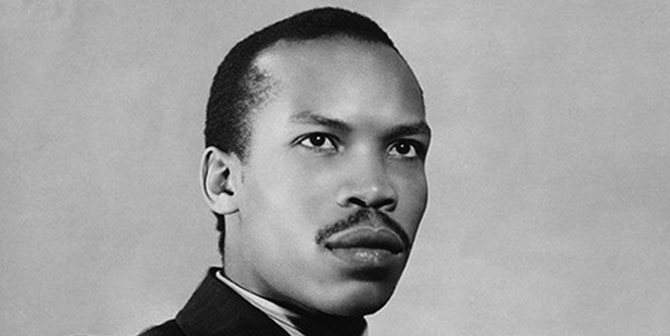

LSE’s Siki Kigongo says that being present at Binyavanga Wainana’s recent lecture at LSE helped humanise the reality of the persecution homosexuals are facing in several African countries.

Listen to Rough Cut Chapter 2 of Lost Chapters.

“I am a homosexual, Mum”- The title that catapulted Binyavanga Wainana into international headlines. Set in his hometown of Nairobi, Kenya, Wainaina’s piece could not have come at a more crucial time with bordering country Uganda having passed the anti-homosexuality bill. It also came at a time when Nigeria, a country Wainana calls his second home has criminalised any same-sex relationship or its promotion, with ramifications being torture and up to 14-year jail sentences. Some would argue that Wainaina’s lost chapter taken from his memoir was not only a pointed but also an intentionally provocative act.

Entering the public lecture last week, it was impossible to miss Wainaina. Clad in a bright yellow suit, his blue Mohawk on display, his presence was vivid. Standing in front of a packed room, Wainaina went on to read from his unpublished second chapter. Taking us from a hospital ward in Albany, to his first homosexual encounter in London, to a night with a woman in a hotel room in Kenya, Wainaina does not lie when he calls himself “a time machine”. His tale tells of an African man seeking for a truth within himself. The piece was blunt, intimate, and came alive as he jolted us from the past to the present with his writing and his play on tenses. His humour is one of his most definitive traits, and we were left at one moment in fits of laughter as he told his story with retrospective comedy, to points of sadness as he reminded us of the inner battle he faced, seeking acceptance from his friends, family and himself. As he said, “there was no more escaping”.

Wainana also spoke on his decision to come out, and the way in which he did so. His timing seemed almost calculated as he joked that he “managed to get all my (his) Nigeria trips out of the way first”. At a time where homophobic rhetoric has become prevalent across the African continent today, his brave piece was probably what Africa needed. Wainaina said he needed “an African conversation, an exchange of hearts”. It was not about the money. It was about a personal journey. While many consider the timing to be strategic considering the current situation in Africa, he described it, as “laws that were simply winds blowing in a turbulent life”, there was no direct correlation. Perhaps, it was just fate.

In his lecture, Wainaina recounted the story of a friend of his who passed away from an AIDS-related illness. His life was dedicated to working with sex workers and educating them on HIV and AIDS, although, quite ironically, his denial was what killed him in the end. The failure to accept his own status. “Shame cannot be accounted for”, Wainaina said, and despite possible consequences, through his declaration, all he wanted “was a better act of being a citizen”. Listening to his story humanises the reality of the persecution homosexuals are facing in several African countries; it puts a face on the struggle they have to encounter.

On the 24 February 2014, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni passed the controversial anti-homosexuality bill criminalising same sex relationships in Uganda, and for Ugandans abroad asserting that they be extradited for punishment back in their home country. The clampdown is not restricted to Uganda, and homosexuals within Africa are under unprecedented attack. Gay rights seem to be taking severe blows. This year we have witnessed a surge of anti-homosexual sentiment driven by “African conservatism”, over zealous religious movements, domestic politicking, and anti-West posturing, which in turn has led to harsh new legislation in countries such as Nigeria. The concern now is that others are likely to follow.

Binyavanga sees homophobia as a rebuttal to imagine beyond prearranged parameters of desire and the body, a refusal to imagine that there are multiple ways of being African just as there are multiple ways of defining love. When speaking on the roots of these restrictions Africans have chosen to live within, he refers to history. The history of Colonisation. Colonisation was a system that sought to control how Africans lived and to define the limits of their imagination. It set up boundaries, from the educational system to the religious structures. It was a time in which Africans were discouraged from being independent, from thinking outside the box, from being innovative. Perhaps it is this burden of oppression that has festered into the recent anti-homosexual laws in Africa; the same logic of governing the masses by blunting their ability to imagine multiple ways of being.

At the root, analysts and pundits across the board argue that Africa’s homophobia is political: domestic politics trumping both human rights and threats of aid cuts from Western donors. When asked on whether aid should be used to leverage gay rights, Wainaina strongly disagrees. But then how should this problem be dealt with? The definitive answer we do not know, but with people like Wainaina leading the cause, perhaps one day we shall find one.