As the Hargeysa Cultural Centre opens during the annual International Book Fair in Somaliland, LSE alumnus Giulia Liberatore highlights how diaspora is transforming a region with no access to IMF or World Bank loans.

“This country is the product of our imagination,” Edna Adan stated boldly, addressing a cheering crowd at the opening of the 7th Hargeysa International Book Fair. Adan, former Foreign Minister and founder of the maternity hospital in Hargeysa, had been assigned to speak about the “imagination”, the theme of this year’s festival. Initially concerned that the topic was “too abstract”, she had soon come to realise that this creative energy had in fact fuelled many of the country’s achievements of the last two decades, including the Book Fair.

Over the past seven years, the Hargeysa International Book Fair has played a special role in the Somali-speaking regions, facilitating discussion and sharing of work and ideas among writers, artists, poets and thinkers from all over the Horn and beyond. Jama Musse Jama, a publisher in Somaliland and an academic in Italy, and Ayan Mahamoud, director of a UK-based Somali arts organisation, are responsible for organising what has become the largest book fair in the Horn of Africa.

At this year’s Book Fair which took place in August 2014, Jama and Mahamoud launched a new initiative, the Hargeysa Cultural Centre. With a theatre, art gallery space and library, the centre has been set up in partnership with the Rift Valley Institute and support from the European Union. Intended as a cultural hub for artists in the Somali regions, it will host the annual Book Fair as well as run a wide range of activities for locals to engage with Somali arts and culture, stimulating the revival of the arts in the region and providing one of the first cultural institutions of its kind since the civil war.

Having followed the Book Fair at a distance since its inception, I was thrilled to attend the 2014 version in the capital city of Somaliland – the former British protectorate that declared independence over two decades ago. Despite years of peace, stability and democratic rule, Somaliland is yet to be recognised internationally and its very existence is more often overshadowed by media reports of Al-Shabaab militants, piracy and conflict in the southern Somali regions.

The festival brings together an eclectic mix of activities ranging from book presentations to dancing, theatre, a poetry competition, and a final day acrobatic performance by Somaliland’s only circus company. Photography and creative writing workshops run prior to the festival, and Somali and English language books that are on sale vanish quickly from the stalls as participants race to purchase their own copies, eagerly holding them out for artists to sign.

For many of the participants, the time spent socialising, mingling, and at times heatedly debating, is equally as precious as engaging in the panel sessions. Local poets in attendance this year, such as the famous “Hadraawi”, welcomed artists and scholars from across the globe – rare visitors to these parts of the world. Young writers from the diaspora, such as the winner of the Granta Award for Best Young British Novelists, Nadifa Mohamed, and activist and writer Igiaba Scego, presented alongside other young local and regional artists. Every year the festival seeks to encourage collaborative work with artists from across the African continent; this year Malawian guests brought their own tunes, rhythms, and wisdoms to the fair.

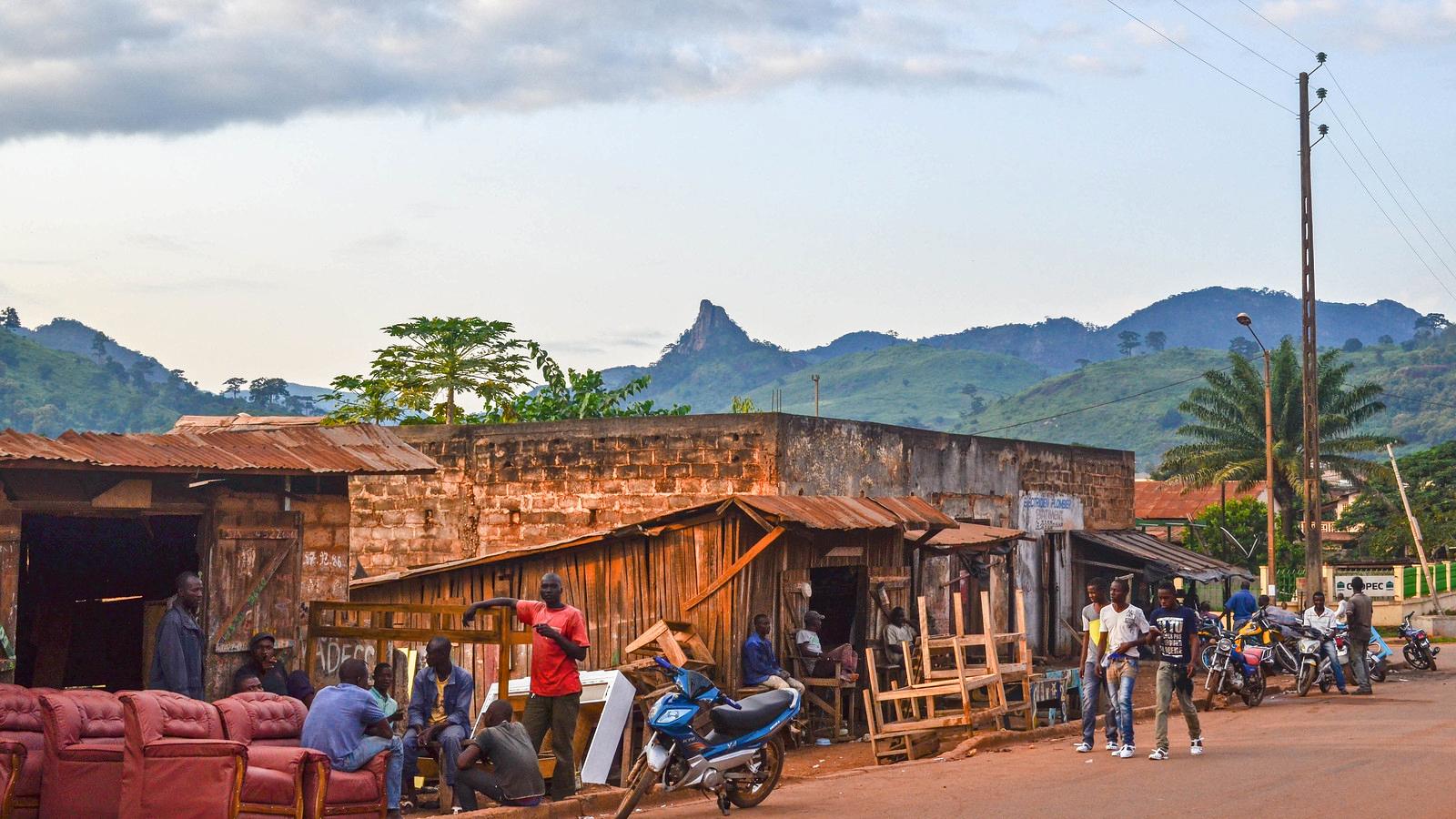

The festival coincides with a festive season in Hargeysa, as many from the diaspora return for their summer holidays, to visit relatives, travel the country, or scout out possible business opportunities. Like many of the newly-built homes, flashy hotels and trendy cafes and restaurants in Hargeysa, the festival too is a diaspora import. These contributions are crucial to a state that is unable to access IMF or World Bank loans and that attracts limited foreign investment because of its lack of recognition. As the Minister of Planning, Saad Ali Shire explained at a recent Hargeysa conference on “Remittances, Compliance, and Financial crime”, diaspora contributions constitute 25-30% of GDP, and are crucial to stabilising the local currency and balancing trade imports. Over the last year, the diaspora has been fundraising to build a tarmac road that will connect Erigavo, in the east of the country, to the capital, speeding up what is now a long and arduous journey.

During my stay in the city I attended a lavish “diaspora dinner party” in a vast hall seating thousands at Guuleed Park Hotel, a recently renovated hotel in the city centre, which was hosted by the President of Somaliland. While the aim of the event was to welcome the diaspora home and thank them for their continued support, it was also a show of respect by the government, underlining the diaspora’s vital role in the present and future economic and political development of the country.

Over the last 20 years most of the state-building and development efforts, including those from the diaspora, have prioritised economic, financial, and political growth. This is also reflected in the aspirations of many of the youth. Viewing the successes of the telecoms and remittance companies, and the rapidly flourishing private sector, most of the young opt for business, management, and IT degrees. Among those who remain in Somaliland, many hope to work in the NGO world or to set up their own businesses, a large majority of which cater for the development market.

While these investments have of course been crucial to a city that was bombed by Siad Barre’s forces in the late 1980s, Jama and Mahamoud have come to realise that their country will remain impoverished if it does not create a space for the arts. Most of the cultural institutions that had existed prior to the civil war, including a large library and a theatre, are no longer standing, and without these much of the cultural and artistic heritage of the country will remain in the minds and memories of an elderly population. The young have little access to this legacy, but also lack spaces to read, write, and imagine for themselves. The Cultural Centre serves as an important reminder that a society needs more than material prosperity in order to thrive.

But as with other diaspora interventions, the Centre is not without its critics. Liberal debate and deliberation, music, singing and dancing, and the absence of gender segregation, are not unanimously welcomed, particularly by Islamic reformist groups which have flourished in the region in recent years. Nonetheless the guests at the fair, such as the renowned critic and writer Nuruddin Farah, did not feel compelled to adjust their tone or alter their language, and continue to speak untamed. Similarly, Jama and Mahamoud, who are of course mindful of their critics, have no intention of shying away. They will continue to dream and imagine, hoping that Somalilanders will follow suit.

Giulia Liberatore is currently working at the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford on a project entitled ‘diaspora engagement in war-torn societies’ funded by the Leverhulme Trust as part of the Oxford Diasporas Programme (ODP).