Civilian protection sites created by the United Nations house large numbers of internally displaced people in crowded conditions, making them vulnerable to illness from COVID-19. Advice for residents to go home or physically distance is not only impossible but distracts from more useful measures which, argues Naomi Pendle, must draw on local leadership.

On Wednesday 13 May the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan confirmed the first two cases of COVID-19 in the UN Protection of Civilian Sites (POCS). These densely populated UN sites, which currently house 190,000 people, are a particularly dangerous place to live during the COVID-19 pandemic. In December 2013, South Sudanese people fled to UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) bases in order to seek protection from intra-army conflict and door-to-door killings. People also fled to these POCS in the subsequent years as violent conflict continued. Many of those who entered have never moved out. These POCS are surrounded by barbed wire, ditches, patrolling, armed peacekeepers and UN tanks. UNMISS and humanitarians provide food, water and shelter.

As well as being densely populated, people living in the POCS need to congregate to access food, water and bathrooms, and have already proven to be vulnerable to disease outbreaks. In sites with similarly dense populations, COVID-19 has spread incredibly fast and proved especially deadly.

Measures to prevent COVID-19 entering the POCS would never have worked once there was community transition in South Sudan. People have always flowed between these POCS and the neighbouring towns. At the time of writing, community transmission in the country is already prevalent. While South Sudan currently has only 290 confirmed cases, most people have not been tested and local reports suggest a rise in respiratory illness. Even if cases are currently limited to only 290, there will be over 100,000 cases within a month and over a million cases by mid-June (based on crude estimates that cases double every three days, as has happened elsewhere, although transition rates will vary).

The dangers of COVID-19 for POCS residents are not limited to them catching the virus itself. Elsewhere, COVID-19 measures and restrictions have brought hunger. Yet, POCS residents could face mass starvation. People living in these sites are dependent for their survival on UN staff and humanitarians trucking in food and water. The UN and humanitarians are prepared to keep providing these services. However, patterns of testing of COVID-19 in South Sudan have presented the POCS as a dangerous place.

The first confirmed positive infection in the POCS was a UN worker, although untested community transmission in border regions was likely already ongoing at the time. This prompted the government to temporarily close the gates to the POCS (including for humanitarians) with a justification of attempting to contain this apparent danger. This pattern appears likely to continue. Regular testing of COVID-19 in the POCS will make COVID-19 more visible here than in the wider population, potentially providing flawed justification for draconian measures. Prolonged periods without UN and humanitarian access to the POCS will be deadly for residents.

Just go home

In March 2020, UNMISS staff ‘very strongly encouraged people in the POCS to return home’. Historically during epidemics, South Sudanese have often left towns and travelled to rural areas, the reduced connectivity and significant spacing between homes in villages making them safer. But for most residents, the assertion that they should go home is, at best, nonsensical and, at worst, pushes them towards dangerously violent realities. While the Bentiu POCS in particular has a large population who had lived in rural areas until 2015, and some residents from here and Wau did apparently follow the advice, many will not leave despite the deadly threat COVID-19 poses.

No such place as ‘home’

The most notable reason for staying in the sites is that no POCS residents’ home has remained unchanged by war. In Juba, residents’ urban homes have often been occupied by others over the last six years. Histories of land governance in Juba make POCS residents concerned that they may be unable to reclaim their homes. In Bentiu and Malakal, many houses from 2013 are no longer standing. These changes of ‘home’ are not an incidental by-product of war, but instead conflict over land (whether over houses, neighbourhoods, cities or whole regions) has driven the war.

Many POCS residents, further, have never had a home in a village but have grown up in urban centres. Seeking safety in rural areas during epidemics and periods of hunger requires someone to have reliable social networks and relationships in order to access food and support from others in times of need. Many of those who lived in urban centres in 2013 had been in exile during the 1980s and 1990s, with multiple generations passing since life was really lived in the village. Their social connections and, therefore, means of survival are stronger in the POCS.

Thiele riek mi mat ro Jo riek mi dong - another problem should not be added on top of an already existing problem

On top of all this, the focus on COVID-19 ignores the other perils that South Sudanese have to face. Deadly violent conflict remains likely. Between 2013 and 2018, nearly 400,000 South Sudanese died as a result of the war. The 2018 peace deal between the South Sudan government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in Opposition (the main armed opposition) brought hope of peace and respite from violence. Yet, the warring parties are only now implementing the deal. Recent debates over the allocation of national and state level government positions are already causing tensions. The implementation of the agreement, especially at the local level, will highlight the lack of actual consensus between the parties and is already escalating fighting in South Sudan. On the 16 May 2020, there were further violent clashes in Jonglei State. Many of those fleeing the Bentiu POCS are returning to southern Unity State which could see renewed fighting. People ran to the POCS for protection from previous armed conflict, and POCS residents have to navigate their own safety, as well as the political demands of the warring parties. Ill-health is only one additional risk among a collection of life-threatening hazards.

Lack of trust in UNMISS

The POCS have long been a conundrum , UNMISS staff have had to grapple with a regular flow of almost impossible dilemmas and, in 2019, a UN Secretary-General’s report described them as ‘untenable’. UNMISS staff, on a day-to-day basis, have had to carefully balance the complex interaction of norms of absolute sovereignty and protection. From their outset, POCS have also experienced armed attacks from outside, as well as violence among residents. Furthermore, political characters, aligned with the armed opposition, have visibly politicised residents and the leadership structures of the camp. The complexities of this balance have resulted in chiefs, peacekeepers and UNMISS staff having to make difficult, daily decisions to prevent the POCS from failing. COVID-19 and the risk of large-scale illness inside further increases the danger.

The problematic nature of the POCS for UNMISS since their inception means that UNMISS leaders have episodically encouraged residents to go home. After the 2018 peace deal between the government and main rebel leader, there was another push to voluntarily return POCS residents’ ‘home’ and to change protection around the sites. After the 2015 peace agreement, some Bentiu POCS residents, who had rural homes, did go ‘home’, only to then face large-scale, deadly violent conflict. These experiences waned trust in ‘go home’ messages. In 2020, when UNMISS again encouraged people to leave for COVID-19 reasons, it was reasonably interpreted as a continuity of this pre-existing agenda.

The lack of trust in these messages means POCS residents will now face the COVID-19 pandemic in the sites’ crowded conditions. Alternatively, some of those who do now go from the POCS to rural areas from the POCS will likely carry COVID-19 with them. As the rainy season in South Sudan is now starting, these people will not have time to build their own shelters and will have to live in the huts and homes of others. This will also encourage crowding and the more rapid spread of the virus. It will also increase the demand on people’s food supplies, increasing hunger and malnutrition.

Misplaced hope: survival not escape

The UN, humanitarians and government leaders have lamented both the lack of compliance with COVID-19 measures, and the proliferation of false rumours among POCS residents and South Sudanese more broadly.

Hopeful rumours are common. ‘Thiele riek mi mat ro jo riek mi dong’ [‘another problem should not be added on the top of already existing problem’] is often said in the POCS to highlight that residents already face many problems and cannot face more. This hope should not be understood as a sign of naivety. When there is nothing that can be done to increase safety, hoping that the virus will not come could be wise.

At the same time, like many of us, internationals in Juba have also been slow to admit that community transmissions and positive infections in the millions in South Sudan is likely. Many of the standard public health measures advised by the World Health Organisation and applied in the POCS are not only impossible for POCS residents, but they also distract from measures that could be more useful.

In Africa, ‘shielding’ of the most vulnerable is suggested as a possible solution, where at-risk groups are separated from others, especially in camp-like settings. Creative methods are being developed. But these will rely on local nuances, and cooperation between UNMISS and humanitarians, as well as chiefs and camp leadership in the POCS is vital for these nuances to be realised. Recent antagonism, mistrust and political agendas have interrupted trust between UNMISS and POCS residents and leaders, yet this could now prove deadly. Let us remember that during other epidemics in Africa local leadership has proven crucial to reducing mortality.

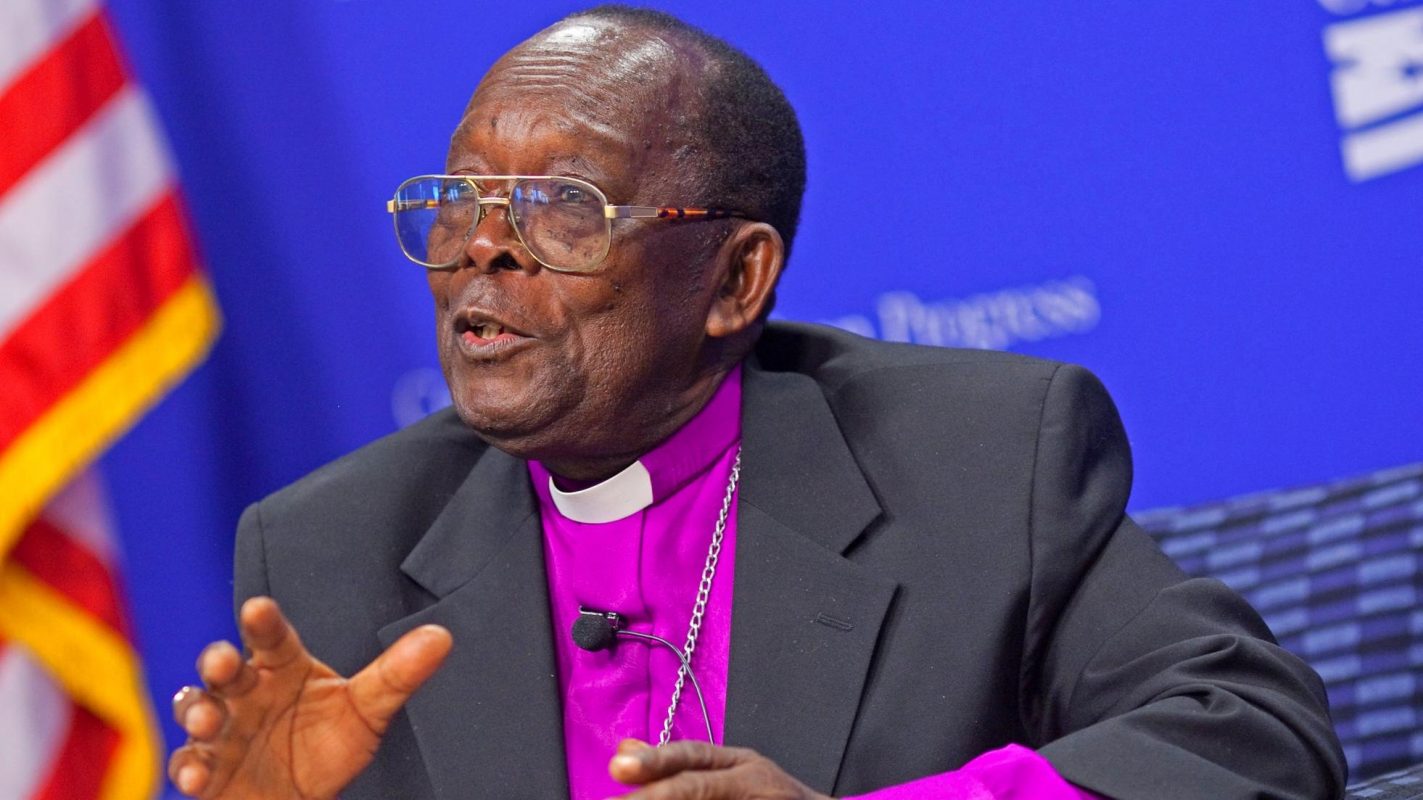

Photo: Images from Bentiu PoC site, South Sudan. Credit: UNMISS licensed under creative commons (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Hi Naomi, you might like to read about our work in South Sudan and refugee camps countering misinformation and promoting solidarity: https://twitter.com/peace_rights

Hi Naomi , your Dad sent this so grateful : yes ” local is best ” both in SS and here in UK with national resources supporting or in the case of SS UN and Agencies. Hope you are well and Jonathan , – he must about 6/7 ? Take care and keep up the good work ,

Patrick and Olivia

My heart goes out to the people who are currently residing within these camps. I am in the process of developing Bir Tawil and will be opening my Kingdoms borders to such people. Please see my website:

http://www.kingdomofbirtawil.net