Eastern Africa’s pastoral drylands have witnessed an influx of large investment to develop the region’s land, resources and infrastructure. In areas inhabited by various pastoral and agro-pastoral groups, these projects have in many cases proceeded with little consideration for local livelihoods and social relations. Jeremy Lind, Doris Okenwa and Ian Scoones argue they have accentuated inequalities and social difference within the host communities.

More than a decade since the investment spike began in the pastoral drylands of Eastern Africa, it is possible to see how a new generation of projects are reconfiguring power, livelihoods and conflict. What do these investments look like in Eastern Africa’s drylands? Do the diverse inhabitants of these lands benefit, or is this a new type of territorialisation? And what types of resistance, mobilisation and activism are evident?

These questions are explored across thirteen different contexts of large-scale investment in our new book, Land, Investment and Politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands. Focusing on local cases, stretching from the Gulf of Aden ports on Somaliland’s coast in the north to the Kilombero rice developments in southern Tanzania, the book highlights diverse experiences and perspectives of investment from the bottom up.

Many pastoral and agro-pastoral societies were marginalised by centralised state power and maligned as backwards by earlier ‘modernisation’ efforts to create sedentary (and compliant) governable subjects. Violence and the destruction of livelihoods was the experience for many. Set against such legacies of contestation and underdevelopment, global investors, project developers and national governments herald new large-scale investment as transformational, ushering in new-found prosperity and secure livelihoods.

When large-scale investments encounter local economies, the social and spatial outcomes do not reflect merely the state’s aspirations of ‘development’ or the interests of large global capital. The outcomes also intersect with local realities and aspirations. Seen from the dryland margins, struggles around the framing and meanings given to investments in oil, wind, livestock, land and water are the crux of many tensions.

Even the most elaborate plans of financiers, contractors and national governments come unstuck and are re-made in the likeness of not only states’ visions of modernity and ‘progress’, but also those of herders and small-town entrepreneurs in the pastoral drylands.

‘Seeing’ and responding to investments

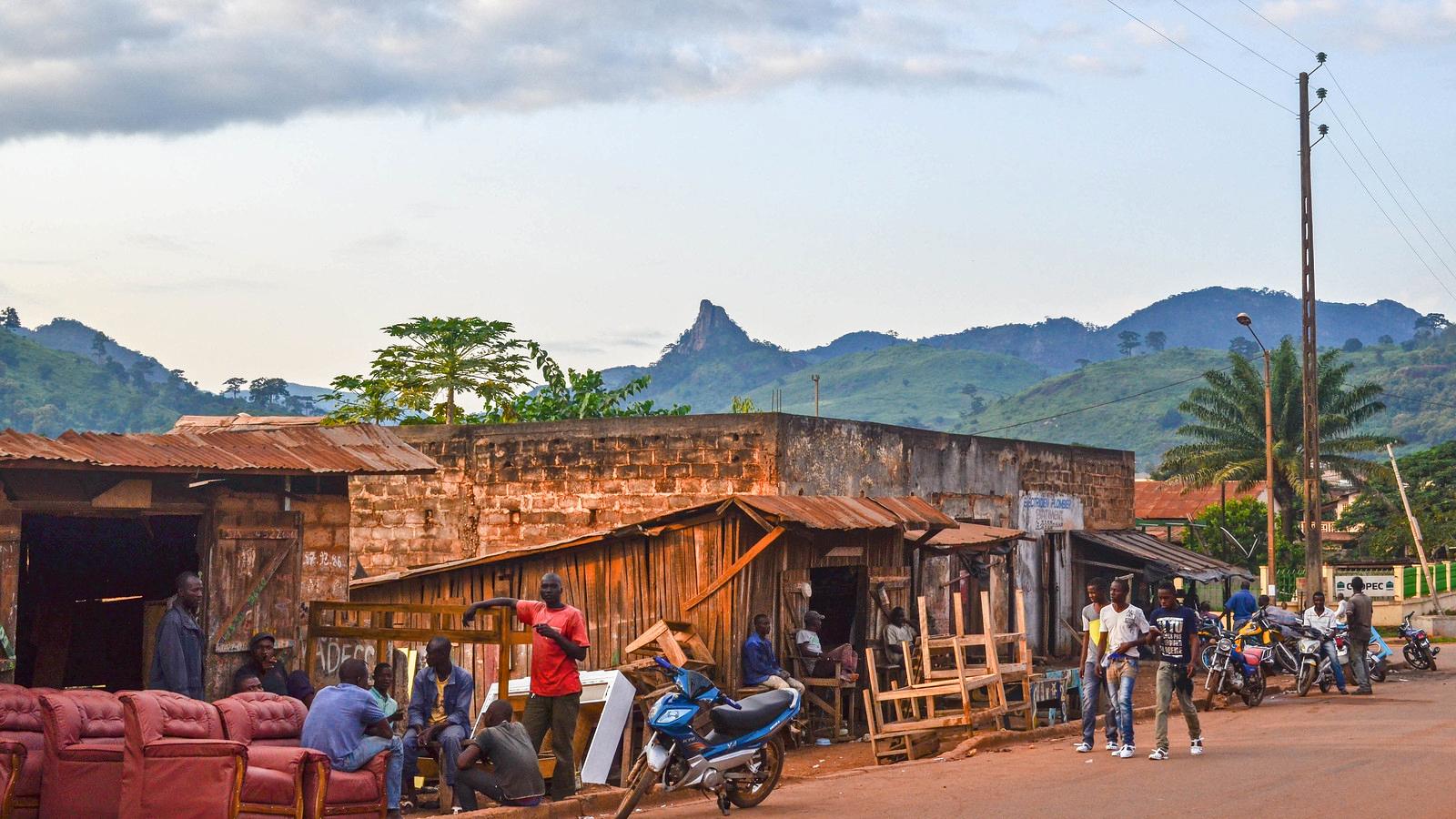

Ports, pipelines, roads, wind farms and plantations are prominent features in the development visions of both national governments and private capital across Eastern Africa. National development plans emphasise the presumed benefits of large outside investment for expanding markets and economic activities in marginal rural areas. Actors in national governments become gatekeepers to foreign investment and are well-positioned to benefit personally from deals.

Investors promote the benefits of project activity to residents of nearby communities through additional programmes in the community, delivering the construction of new infrastructure, easing transport difficulties, promoting marketing activity, providing opportunities for work and creating corporate social investments in bursaries, classrooms and the provision of water, for example. Yet, these efforts at corporate social responsibility have ignited debates around belonging, entitlements and inclusion. In Turkana in northern Kenya, tensions cropped up around the efforts of oil investors to curry favour with communities and stem any potential resistance through ‘participatory’ and ‘consultative’ processes, inadvertently creating asymmetric power relations.

State actors at the sub-national level may not see investments in the same way, however. The position of sub-national political administrations can waiver between embrace and hostility. Mixed views of large-scale investments also often hold among local business elites. Ultimately, investment is something to be welcomed, but the terms of inclusion in land deals, compensation and contract and tendering opportunities dictate the nature of politics.

For example, around new geothermal developments in Baringo in Kenya’s northern Rift Valley, Pokot elites are at the forefront of land privatisation, fencing the most valuable plots along new roads that connect geothermal sites with national infrastructure.

The views of other dryland residents – small-scale pastoralists and dryland farmers – cover a spectrum, from opposition and resistance to the perceived loss of key grazing resources and farmland, to accommodation in anticipation of deriving personal benefit or simple antipathy.

For example, residents of small settlements near the Lake Turkana Wind Power site, also in northern Kenya, blockaded roads to protest their alleged exclusion from investment benefits, including compensation for the extraction of sand and the felling of trees, as well as access to jobs. Even so, at the local level, there is no uniform opinion or interest: while young people seek an economic foothold, elders agitate to uphold precedence for grazing rights and women seek opportunities as cleaners and cooks for contractors.

Ambiguous outcomes, unclear ‘winners’

Exploring ways that large-scale investments are ‘seen’ by stakeholders at various levels of project design, finance and implementation brings into frame the questions: investments for whom? In whose interests? And with what consequences?

The reconfiguration of land ownership and use, while perhaps not as dramatic as earlier ‘land grabbing’ debates feared, has been profound, creating new politics of land and investment in the pastoral regions. Simple narratives of the ‘state’ and/or ‘investor’ versus ‘local people’ do not relay the more complex dynamics and assemblages of interests that mobilise behind, anticipate and pursue large-scale investments. In Ethiopia’s Awash Valley, local Afar elites have become complicit in seeking personal advantage from the state’s investments in sugar estates, which have dispossessed livestock-keepers from prime grazing areas.

Infrastructure and investments have ignited intense competition and the revaluing of land, as local elites and other domestic and foreign investors jostle to claim tracts of land. Far from resisting and obstructing investment, many have sought to position themselves to benefit from it. In Somaliland, intense competition to command a favourable position in wider trade networks are evident in struggles to capture the expected windfall of the Berbera corridor development. A common saying in Somaliland – He who sits close to the cooking pot gets a good bone – is invoked by some far from infrastructure who worry they will miss out from the benefits.

Inequality and mobilisation from below

So, how do communities around the edges of big projects gain more than arbitrary compensation? Local governments and leadership need to be more creative in negotiating investments beyond the national government agreements with developers. It is crucial to demand clear terms of engagement and more long-term benefits for differentiated local stakeholders – not just one-off disbursements or short-term work.

While national governments often side with investment, citizens and civil society alike can press for accountability – through statutory human rights instruments, the implementation of land reforms to guard against grabbing, the enforcement of environmental regulations and scrutiny of contracts by anti-corruption agencies, to name a few.

Meanwhile, as we argue in the book – Land, Investment and Politics – the more imperceptible influences of investments on territory, as well as the economy, politics and citizenship, will accentuate inequalities and social difference that increasingly characterise dryland margins. While there is no simple view ‘from below’, resistance, mobilisation and subversion are something to anticipate as part of the ongoing development of infrastructure, land and resources across Africa’s drylands.

Publication information:

Lind, Jeremy, Okenwa, Doris, and Scoones, Ian. 2020. Land, Investment and Politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands. Woodbridge: James Currey.

Link to open access introductory chapter.

Purchase information.

Photo by Neal Markham on Unsplash