Across Africa, the cost of campaigning is going up and up. This is being driven by the vast amounts being spent on political rallies, writes Dan Paget.

In many democracies in Africa, election campaign expenditure is rising, and rising fast. In an extreme example, parliamentary campaign spending in Ghana rose by 90 per cent in just four years. That expenditure has reached towering heights. In Uganda, £94,000 is spent in the average parliamentary campaign. In Kenya, that number is £140,000. And in Nigeria, it is a dizzying £352,000.

In comparison to the $14.4 billion spent during the US election in 2020, these figures may seem like small change. But for all the talk of Africa rising, GDP per capita across much of the continent is between £400 and £1,500. In comparison to how much money people earn, the levels of campaign expenditure are eye-wateringly high.

This rising cost of election campaigning is important. It changes the role of money in politics. It gives an advantage to better-financed candidates. It gives financiers power over the officials that citizens have elected. It has urgent implications for the future of democracy. However, newly published research reveals that the causes underpinning it have been misunderstood.

Rallying voters, and finance

That research is about election campaign rallies in Tanzania, where between 2010 and 2015 parliamentary campaign expenditure rose 44 per cent. Tanzania is no ordinary place to study rallies. It sits in a region where election campaigns are rally-intensive. During campaigns, 35 per cent of people attend election rallies in sub-Saharan Africa. Tanzania’s election campaigns are the most rally-intensive of all: 62 per cent of people attended rallies in its most recent elections.

What the research shows is that rallies are changing. They used to be produced through labour-intensive practices. The rally site was prepared by an advanced team. Turnout was mobilised by party foot soldiers. Entertainment was laid on by a women’s choir. Politicians were greeted by a welcome committee.

Today, capital-intensive practices of rally production have been integrated alongside those labour-intensive ones. Instead of erecting a stage by hand, a customised truck folds out, transformer-style, into a stage. Rallies are advertised not by callers who walk street by street, but by fleets of vehicle-mounted PA systems. Politicians arrive at rallies at the head of motorcades of hundreds of vehicles that pass through towns and cities in long, ostentatious parades. Or they arrive by helicopters which put on impromptu air shows to dazzle spectators.

Of course, these practices are not unique to Tanzania, or Africa. Successive devices have been incorporated into rallies across the world, and indeed across time, not least to enable them to be covered in other media. But in Tanzania, the rallies of not just national politicians, but hundreds of parliamentary candidates and thousands of councillor candidates are all being upgraded to different degrees as well.

These practices may make rallies more effective as mobilisation instruments, but they have also made them more expensive. In 2015, Tanzanian parliamentary candidates and their campaign managers said they spent £30,000 in these campaigns. Hire of a car for the duration of the campaign cost between £900 and £2,900. Hire of a customised truck with an accompanying mounted PA system cost between £1,900 and £4,800. Helicopter hire came in at between £1,300 to £2,100 per hour.

Candidates hire squadrons of PA trucks. They hire fleets of cars. A number hire helicopters for days at a time. To finance the production of rallies at this scale, parliamentary candidates in Tanzania must have nearly exhausted their campaign budgets. The increase in the scale of rallies has driven up campaign spending.

Not just buying votes or buying time

The cost of rallies is not the usual explanation given for the increase in campaign expenditure in Africa. The usual explanation given is clientelism. African politicians, in these accounts, lavish citizens with gifts, whether to buy votes or exhibit generosity. To win an edge over their electoral rivals, politicians spend ever more on gifts and unwittingly create continuous upwards pressure on spending.

In the global north, research has singled out the modernisation of election campaigning as the motor of campaign spending. In this account, the continuous development of new media, from broadcast television to social media, has created an ever-evolving field of opportunities for politicians and parties to communicate with the public. Yet these opportunities have proven costly to seize. Seeking a competitive advantage, parties have brought on successive generations of public relations and digital specialists to craft and disseminate those messages. They have also spent ever more money on ads to push those messages to the public.

The focus in Africa on clientelist explanations of rising campaign expenditure over modernisation ones is simply out of date. Across much of the continent, the reach of media is growing. Yet what this research shows is that campaign expenditure in Tanzania has not only been driven by a clientelist spiral or the growing penetration of media but also by the capitalisation of rallies.

What causes campaign expenditure to rise changes how and whether it can be curbed, and whether it should be curbed. It will not be enough to run anti-corruption campaigns or regulate political advertising in much of Africa. In Tanzania, and places like it, candidates are not spending to merely buy votes or media time. They are spending to put on the most spectacular shows.

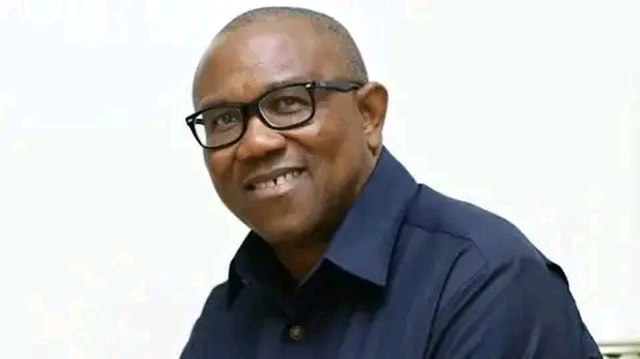

Photo credit: Chadema.

Very excellent and insightful piece.