As China’s Belt and Road Initiative enters its second decade, China’s plans have shifted away from expensive infrastructure projects to smaller and more nimble investments. This throws up challenges and opportunities for Ghana, writes Matthew Rochat.

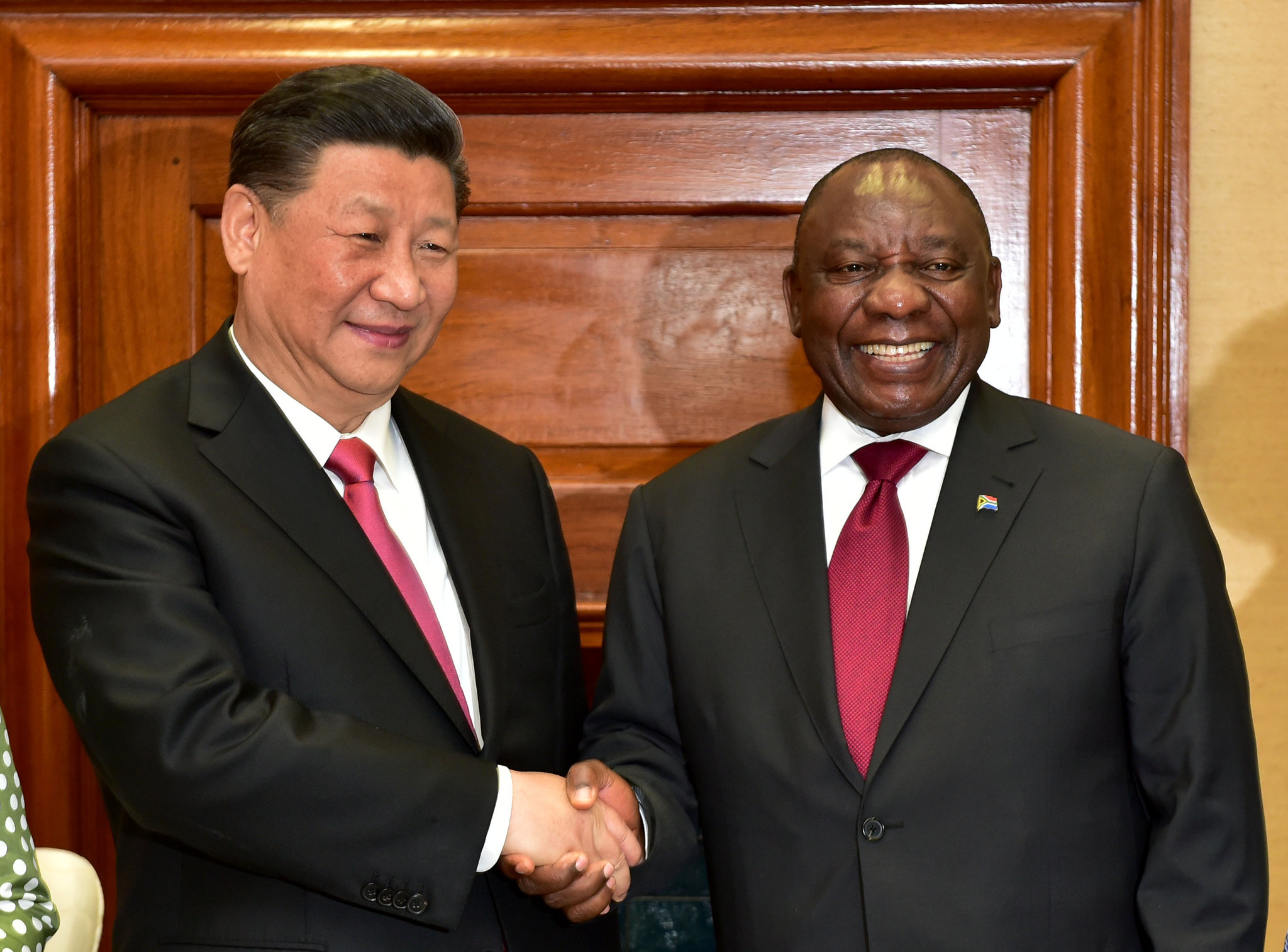

World leaders from over 140 countries, including a delegation from Ghana, gathered in Beijing on 17 October for the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation which marked the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). President Xi outlined his vision for the BRI as it enters its second decade.

Financing is beneficial no matter where it comes from, whether China, the United States, or elsewhere. This is particularly true of infrastructure investment in Ghana, as well as other parts of Africa, where closing the “infrastructure gap” will be vital to unleashing growth and development in the coming decades. Compared to other major economies, China has simply done a better job of delivering on major infrastructure investment projects.

In Ghana, this has involved financing road construction, rural electrification, vocational training centres, maritime ports, coastal fishing sites, digital infrastructure, renewable energy, and more. According to the Boston University Global Development Policy Center’s China Loans to Africa Database, the figure amounts to £1.96 billion of financing by China on projects in Ghana since the initiation of China’s BRI in 2013.

However, in Ghana, there is an understanding that money typically comes with strings attached, whether economic, political, or otherwise. Yet, for many Ghanaians, the risks of Chinese financing are well worth the potential rewards.

Deborah Bräutigam, Meg Rithmire and Ajit Singh have devoted much time and energy to debunking false media narratives of “debt trap diplomacy.” Allusions to mafia-style extortion by Beijing, twisting the arms of political leaders in indebted countries, are more myth than reality.

China has, nevertheless, proven to be a formidable negotiator in debt discussions. Though in some rare cases, China has been willing to forgive the debts of African countries, Chinese representatives have demonstrated an overwhelming preference for extending loan repayments rather than accepting write-offs or financial haircuts. Ghana is currently in debt restructuring talks with China in the wake of a £2.45 billion IMF relief package.

Public debt

Of Ghana’s £45 billion public debt only 3 per cent (£1.4 billion) is owed to China. In fact, of Ghana’s $29.9 billion foreign debt a larger portion is collectively held by members of the Paris Club of creditors such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France (£1.64 billion); multilateral lending institutions (£7.2 billion); and Eurobond creditors (£11 billion).

A similar pattern is seen across Africa. Chinese lenders, both public and private, account for 12 per cent of Africa’s public external debt. While meaningful, this figure represents less than half of the combined debt African countries owe to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, at 24.6 per cent, and even less compared to the 27.5 per cent owed to private bondholders. Chinese financing plays a notable part in the public debt crisis facing Ghana and other African countries, however, there are many other creditors, both foreign and domestic, who have equal if not more outsized roles.

There is also scant evidence that China is intentionally ensnaring Ghana or other developing countries in debt. Examination of the two most frequently cited debt-trap cases, in Sri Lanka and Malaysia, indicate that these controversial projects were initiated by recipient governments pursuing their own domestic agendas and the subsequent debt problems largely arose from the misconduct of local elites.

The geopolitics of money

Although media narratives have portrayed a binary choice between the United States and China, the truth is that the financial environment facing most African countries is increasingly, multipolarity. Rather than being forced to choose one source of investment over another, African leaders and stakeholders can preserve their autonomy. As a sovereign country, Ghana has the right to choose with whom it maintains relations, and in the words of President Akufo-Addo, “Ghana is open for business” to everyone.

This quote is corroborated by the data, which shows that South Africa, France, Mauritius, Singapore, Australia, and India are among the major sources of financing and investment in Ghana. The total stock of foreign investment in Ghana reached £33.6 billion in 2021, including FDI inflows of £2.1 billion in 2021 alone. As a growing West African hub for foreign investment, Ghana benefits from its diverse economic relationships with many actors, both inside and outside of Africa.

After decades of growing investment in Africa, China’s overseas development finance has followed a downward trend after reaching an apex in 2016. Since then, and in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, investment in African infrastructure has declined precipitously. The new era that has emerged has been referred to by Chinese President Xi Jinping as “small is beautiful,” prioritising smaller-scale and more targeted investment projects that have an environmentally and socially beneficial impact. Between 2000 and 2022, Chinese creditors loaned £139 billion to Africa. In 2022, funding shrank to less than £820 million.

Even in the era of “small is beautiful,” China remains one of the most active investors in Ghana, with a total of 16 projects worth £98 million so far in 2023 according to Ghana Investment Promotion Centre’s Jan to June 2023 Half Year Report. The appearance of offices in Accra for Chinese-based tech multinationals such as Huawei, Tecno Mobile, and StarTimes is a sign of China’s shift from hard to soft infrastructure along the Digital Silk Road.

In Ghana, optimism remains despite China’s reduced role. From the local perspective, it is not the responsibility of China or other external actors to ensure Ghana’s development. In the words of, Dr. Patrick Owusu: “The development of Ghana is a shared responsibility between the seat of government and the citizenry.”

Photo credit: World Intellectual Property Organization used with permission CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED