Low compensation, poor process, and a lack of transparency are leaving people in Dar es Salaam worse off as the government tries to implement flood mitigation measures along the Msimbazi river basin, write Maddy Diment, Erica Pani, Mwajuma Mshana and Martina Manara.

In the Msimbazi River Basin in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania regular flooding exposes unplanned settlements to severe health and livelihood risks. Recent adaptation policies implemented to mitigate flood risk along the basin have worthy aims. However, the procedures involved in the displacement and relocation of local landholders have been unfair and unjust. The resultant distribution of risks and compensation has affected the river dwellers unequally, thereby pointing to a severe lack of ‘procedural’ and ‘distributive’ justice in the implementation of these policies.

Foundations for justice

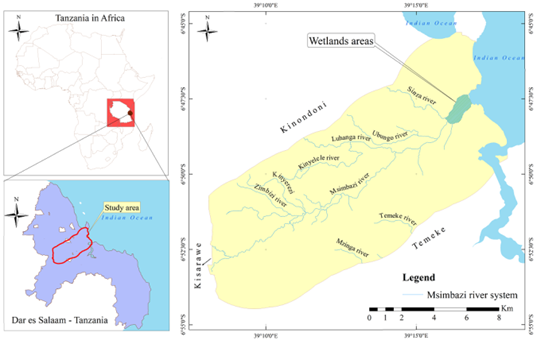

The Msimbazi cuts through Dar es Salaam, a major city on Tanzania’s east coast. For decades, it has endured severe flooding caused by increasingly high rainfalls. Officials and legal proceedings have largely failed to declare the basin as hazardous or environmentally sensitive, meaning that people have settled on flood-prone land. Nor has the government been able to provide adequate serviced land for formal settlement. As a result, despite the floods, the Msimbazi Basin has become home to thousands of informal dwellers.

In 2018, local stakeholders, in partnership with the World Bank, created the ‘Msimbazi Opportunity Plan’. The Plan was designed to match local community knowledge with climate science to identify and define climate adaptation solutions. This included the redevelopment of the most flood-prone areas to form floodwater catchment areas, a marina, and new, more expensive, apartments. It also required the compensation of those landholders facing displacement.

Procedural justice and compulsory acquisition

By 2022, the Plan had evolved into the Msimbazi Basin Development Project, whose focus is to strengthen flood resilience by developing river basin infrastructure, re-settle flood-prone communities, and strengthen institutions to deliver more resilient emergency responses. This combination of prospective and corrective measures is important for effective flood mitigation. However, effectiveness does not necessarily equate to fairness.

For instance, to establish what compensation residents would receive for their compulsory displacement, the Project involved four procedures: local community engagement, property valuation, ‘offer’ delivery, and a complaints process. According to landholders in Kigogo Mbuyuni on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam, none of these steps was just or fair.

Regarding the engagement of local residents, a typical complaint was being ‘spoken at’ by officials rather than ‘listened to’:

“The Mtaa Chairman said that we would be given the chance to ask questions… However… the Government officials said they were in a hurry, so there was no time to listen to our questions.”

The valuation process was seen as inaccurate with many respondents noting that valuable improvements were left off their compensation offers while other less valuable items were included:

“They have written to pay me for that tree outside which is not even for fruit… Yet they haven’t written about my well that I built for more than 10 million TSh… Why is this tree worth more than my well?”

Others noted that while they appreciated the valuation officers coming to their plots, the lack of transparency was concerning:

“At no point were any details given for the valuation rates… They wrote down ‘tree’, but [not] its value. They wrote down ‘fence’, but [not] the amount.”

Worse still, the majority of landholders felt threatened when it came to signing their offer letters. Police were present throughout, while local media were barred from attending. As a result, many landholders felt forced to sign.

Likewise, the complaints process felt biased and untrustworthy. Residents felt bullied and intimidated into signing the offer rather than complaining. Others wanted to register a complaint but felt powerless against the government. Others felt a distinct lack of trust towards those in charge who refused to officially stamp their complaints. As one resident summarised:

“Honestly, I was worried that there might be some game going on amongst them”.

A lack of distributive justice

When residents heard that the World Bank was involved, they felt assured that the compensation would cover the replacement of their properties and help them improve, or at least restore, their livelihoods. But reality fell short of their expectations. One respondent, who had a formal property right, was appalled that no one would be paid for the value of the land:

“We thought we would be paid 100,000TSh per square meter. But on the offers, there was no land compensation for anyone… We were so surprised! I mean, let’s say, ‘yes: land is government property’. Then where have we built our houses? On air? On water? It wasn’t fair at all!”

Others underscored that being moved from Kigogo, which is close to the centre of town, without fair compensation would destroy their economic opportunities:

“This place is my office. While I am here I am earning money to provide for my family. That is why I don’t want them to take it away from me by paying me such a small amount of compensation.”

Many landholders were left distraught and disillusioned by the process. Their homes, social networks and livelihood potential were being taken from them, and the government did not seem to care, as one landholder stated emotionally:

“The government has treated us in such a way that we have pains in our hearts. The money they will give us will be just enough to buy our coffins and shrouds.”

Looking ahead

In November 2023, President Samia Suluhu Hassan intervened in the process stating that those being displaced along the Msimbazi basin would receive a flat rate for the value of their land. The need for such high-level intervention exposed the procedural and distributive injustices that can arise as local actors grapple with the complexities and uneven power relations of climate-risk adaptation. In the case of Kigogo, Dar es Salaam, despite the efforts of the World Bank to construct a fair and just framework, the local community faced displacement without due process or fair compensation. As such, questions remain regarding how states can be made to take their responsibilities seriously and treat communities fairly. Climate risk is not set to reverse any time soon and justice issues with local climate-risk adaptation will continue to take their toll on the most vulnerable populations.

Photo credit: Authors