In our rapidly changing world, are Africa’s highly educated and skilled still leaving their home countries in search of greener pastures, Scott Firsing delves into the numbers to find out.

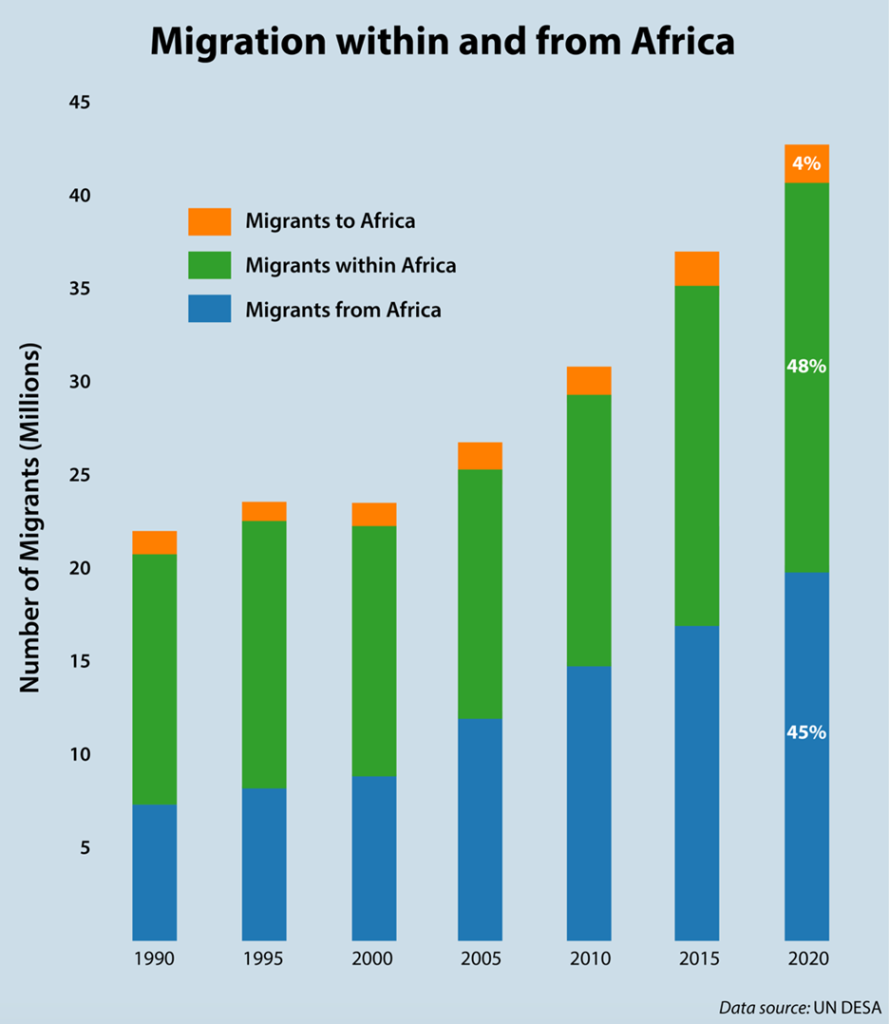

Given the complexity of the topic and the difficulty some African countries have in tracking this data, obtaining exact African migratory numbers is a challenge. However, some estimates can help us. In 2020, the UN said migration from Africa had increased by 30 per cent since 2010. That’s another 40+ million Africans migrating. Like previous estimates, intra-African migration is still the highest percentage of this movement.

Intra-African migration has a high labour component. Around 80 per cent of intra-African migration falls into this category and consists of mostly lower-skilled workers. The industries include agriculture, construction, mining, retail, and tourism, among others. Regional economic hubs like South Africa, Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire with their employment opportunities and better wages continue to be hotspots for these migrants. On the other hand, the highly educated and/or skilled African nationals continue to be pushed or pulled towards France, the UK, the US, or Canada.

Comprehensive immigration data from these countries show rising African emigration. A report from France in March 2023, highlighted that seven million immigrants now make up 10.3 per cent of France’s population. This is up from 6.5 per cent of French residents coming from abroad in 1968. The data also shows a trend of more people immigrating to France from both North and sub-Saharan Africa. More than 12 per cent of migrants to France were born in Algeria, another 12 per cent in Morocco, and 4 per cent from Tunisia. The Canadian Census 2021 data shows growing African populations from Nigeria (109,240), Ethiopia (43,205), the DRC (37,875), Cameroon (33,200), Somalia (32,285), Eritrea (31,500) and Ghana (28,420). America is no different. In 2019, around 2.1 million immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa resided in the US, a 16-fold increase since 1980. There are now 5 per cent of the total US foreign-born population of 44.9 million people. Fifty-three per cent come from Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, or Somalia.

Brain drain strain

Digging deeper into subsets of immigration data like specific work or study visas provides further clarity about the brain drain. According to UK Home Office data, over 330,000 total visas were issued to Sub-Saharan African nationals in 2019, which was an increase of 95,000 compared to 2016. Work visa data ending in September 2023 shows over 78,000 visas granted to Nigerians alone. Zimbabwe and Ghana made the top 10 list as well, with 44,714 and 26,013 work visas approved. It’s a similar story for UK study visa numbers, which are vital as students often contribute to brain drain by settling long term and working in host countries. Nigeria is the African leader with 111,577 UK study visas out of a global total of 639,087. This global study visa total is up from 276,889 visas awarded for the year ending September 2019.

African scholars also continue to flock to America to study. According to the 2023 Open Doors report, there are around one million foreign students in America. Although still dominated by China and India, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest rate of growth among world regions, growing by 18 per cent with 50,199 students. We see the most students from Nigeria with 17,640. Ghana was second with 6,468 and entered the top 25 places of origin for the first time.

Combining the above with more industry-specific data provides more insight into who is exactly leaving and why. The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) dataset, for example, shows tens of thousands of NHS openings now being filled by a growing number of Africans. New NHS nurses from Ghana rose 1,328 per cent between 2019 and 2022. There are now more Ghanaian nurses working in the UK than in Ghana. Since 2016, the overall proportion of African-born NHS staff has risen from 1.8 per cent to 3.1 per cent with Botswana and Kenya also featuring.

These rising numbers are having detrimental effects on Africa’s health staffing. A 2023 World Health Organization (WHO) report points out that 40 African countries or roughly 80 per cent of the continent have significant health staffing shortages and many are leaving to work in other countries. On average, according to the WHO report, 500 nurses leave Ghana for the West every month. Egyptian data shows around 9,000 medical students graduate annually from Egyptian universities, but 65 per cent go to work abroad. In Nigeria, there is now one doctor for every 5,000 patients, compared to the one in 254 ratio in developed countries. Around 9,000 Nigerian doctors moved to the UK, the US, and Canada between 2016 and 2018. More than 75,000 nurses have left Nigeria since 2017. The WHO believes the sub-Saharan Africa healthcare crisis will intensify and the region will be short 5.3 million health workers by 2030.

The story appears to be similar for African engineers. Engineering bodies see a South Africa plagued by losing quality engineers to emigration. International opportunities are part of the reason. Sometimes they switch industries. It can also be due to dysfunctional government institutions. The bigger problem: the individuals who leave are the more experienced engineers aged 45-60, which means young African graduates lose sorely needed mentors.

The positive news is that financial remittances have grown alongside the upward migration numbers. The UN stipulates that remittances are a “critical source of external finance for Africa, with over 200 million African family members” relying on this money for survival. Remittance flows to Africa have doubled over the last decade and reached £80 billion in 2022. This has even surpassed the level of funds received through Official Development Assistance and Foreign Direct Investment. The UN highlights that, in some African countries, remittances represent over 20 per cent of Gross Domestic Product.

Will these upward trends continue?

Expect all aspects of African migration to rise. Firstly, the continent’s population is expected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050, up from the current 1.3 billion. Moreover, Sub-Saharan African countries are on a path to be more affected by human capital flight because of numerous political, economic, and environmental reasons compared to other more developed regions.

The importance of intra-Africa migration will endure, but more comprehensive data about this trend in the future would be welcome. Specific African governments and continental bodies like the African Union have a crucial role in this endeavour. One solution is industry-specific government work or study categories that allow for better tracking and understanding of the situation.

Great talent has left African shores over the past 15 years; doctors, economists, engineers, IT experts, and academics to relocate to distant lands with no intention of returning. The larger and harder question to answer is what impact this emigration has on the African country they left. Only time will tell if it poses a significant threat to Africa’s overall aspirations for prosperity.

Photo credit: Dan Brekke used with permission CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED