We need an intelligent debate on whether 16- and 17-year-olds should vote in the EU referendum, says Richard Berry – not least because the notion that different age groups have very different policy priorities is misguided, at best.

We need an intelligent debate on whether 16- and 17-year-olds should vote in the EU referendum, says Richard Berry – not least because the notion that different age groups have very different policy priorities is misguided, at best.

People hoped, or feared, that the lowering of the voting age for the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 was going to set a precedent. They should have remembered that precedents are only as strong as the powerful want them to be. The House of Lords voted to allow 16 and 17 year olds to participate in the upcoming EU referendum, but it seems the government is prepared to overturn this decision, with the Commons already having rejected the proposal. We’ll see.

This is another example of major constitutional issues being considered as an afterthought to run-of-the-mill political struggles of the day. The politics of the EU referendum are complex, with the government forced to delicately build a supportive coalition, crossing party lines, to gain support for its proposals. Changing the electoral franchise is probably a further complication they can do without.

For those of us who support votes at 16, it will feel like a huge missed opportunity if the voting age is not lowered. Given the spread of political opinion in favour of this reform, it is beginning to feel inevitable that 16- and 17-year-olds will be enfranchised eventually. How much better to do it ahead of such a definitive vote for the country, where the choice put to voters – unlike the dispiriting compromises on offer at election time – is clear and profound?

If the debate is going to rumble on, let’s hope it becomes more intelligent and informed than it has been to date. For instance, both the pro and anti camps like to cite the many other things young people can and can’t do as evidence for their case. On the one hand, people can join the army at 16, so they should be able to vote. On the other, they can’t fight on the front line until 18, so they shouldn’t.

It’s circular logic, either way. Young people acquire rights and responsibilities on a continuum, depending on the nature of the activity, the risks involved and the level of maturity required. If we start using the age young people can buy a pint as our guide for when you can vote, what happens if the drinking age is lowered? Or increased? We should, of course, decide the case for votes at 16 on its own merits.

Sceptics point to societal changes as reasons to maintain the current voting age. Young people stay in education longer, and live at home longer than previously. Indeed. Education was made compulsory until the age of 18 (by a parliament under-18s could not vote for). The jobs and housing markets prevent many young people living more independent lives (because of policy failures by governments they did not choose).

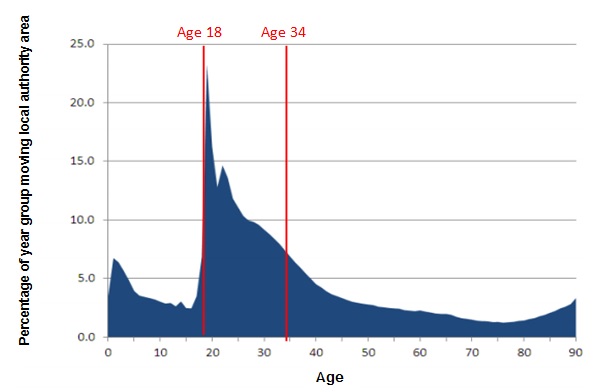

The fact that 16- and 17-year-olds tend to be in school and living with parents is the very reason why lowering the voting age makes sense. People are more likely to vote when they live in a settled community, still subject to the socialising effects of education and family. It’s silly to wait until 18, when people have moved home – probably without knowing how to get on the electoral register – and are facing all the competing pressures of adult life. Figure 1 below shows just how many people move between local authority areas at this age in the year to June 2012, according to Office for National Statistics data.

Proportion of England and Wales population moving local authority areas by age

Although the case for votes at 16 is strong, we should be wary of hyperbole in the coming debate. Even the most level-headed of proponents can get carried away. Take Polly Toynbee, bemoaning the government’s refusal to lower the voting age for the referendum in the Guardian:

Imagine the radical change if candidates had to vie for school pupils’ votes as eagerly as they press the aged flesh in old people’s homes: you can bet that the same free bus passes would soon be on offer to under-25s. The young need to be taught how money follows votes. The rich and the old vote, so that’s how the cash is distributed.

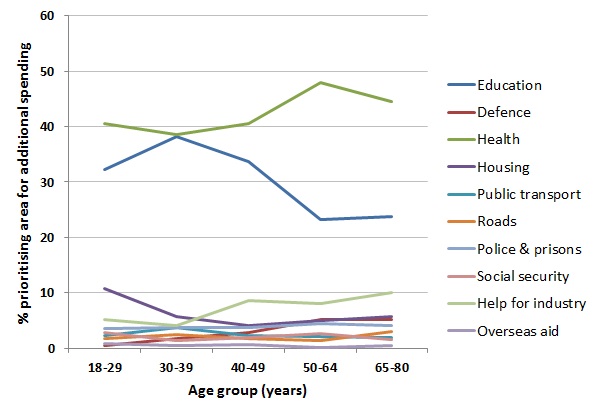

This is mistaken and misguided. Mistaken because the evidence that people of different generations have markedly different policy preferences is slim, at best. As analysis by Craig Berry and myself has shown, views are remarkably similar across age groups. Figure 2 below displays British Social Attitudes data on spending priorities across age groups. And why would we expect age groups to have wildly differing views? Age is a dynamic characteristic – every young person gets a little bit less young with each passing day. Not to mention the fact that people surely think not just about themselves but about their families – children, parents, grandparents – when figuring out their opinions on things.

Public spending preferences by age group, UK

It is misguided, too, because even if it were true that 16-17 year olds were inclined en masse to force a shift in politicians’ priorities, that’s not an argument likely to convince anyone on the fence about this reform. It will only feed their fears about the impact of enfranchising more young people. The EU referendum brings that argument into sharper focus – if a poll said 51% of 16-17 year olds would vote to leave, what incentive is there for the pro-EU camp to support their enfranchisement? Or vice versa. The truth is that, numerically speaking, 16-17 year olds will have no more electoral clout than 26-27 year olds, or 36-37 year olds, and so on. Enfranchising them won’t create a new politics, just a more inclusive version of politics as usual.

A more inclusive version of politics as usual – I accept that’s not a very rousing call for reform. But it’s a start.

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit. He is also a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and runs the Health Election Data project at healthelections.uk. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

This blog represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

3 Comments