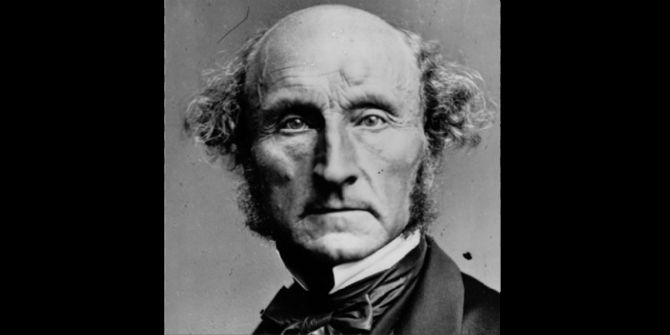

In an ‘epistocracy’, only some people would be allowed to vote. Those who advocate this system have cited Brexit and Trump’s election as evidence that the franchise should be restricted to those who have sufficient ‘political knowledge’ to use it. Linsey McGoey (University of Essex) explains why, contrary to their claims, John Stuart Mill would not have endorsed this dangerous form of authoritarianism.

In an ‘epistocracy’, only some people would be allowed to vote. Those who advocate this system have cited Brexit and Trump’s election as evidence that the franchise should be restricted to those who have sufficient ‘political knowledge’ to use it. Linsey McGoey (University of Essex) explains why, contrary to their claims, John Stuart Mill would not have endorsed this dangerous form of authoritarianism.

What does the political philosopher John Stuart Mill have to do with Brexit? Quite a lot, judging by his popularity in Brexit discourseland.

Mill’s name is often brandished to defend the arguments of competing ideological camps, sometimes in areas that seem a planet away from Brexit. A good example is the concept of ‘epistocracy,’ which is a new, trendy way to describe an old idea, one that stretches to ancient Greek debates over the value of democracy. Like Plato before them, epistocrats are explicitly anti-democratic. Their main belief is that anti-democrat government by elite ‘knowers’ is superior to universal suffrage.

Libertarian advocates of epistocracy such as Jason Brennan, a Georgetown political philosopher, are having a ‘good’ Brexit, because they think the vote to leave the EU proves true one of their own pet ideological theories: that voters are incompetent and prone to vote against their interests.

Brennan has pointed to Brexit, as well as to Donald Trump’s 2016 win, to bolster the main idea behind epistocracy: the idea that ‘voter ignorance’ is undermining good governance, and that only citizens who demonstrate sufficient ‘political knowledge’ should be allowed to vote in today’s nations. They suggest, for example, that we could trial ‘voter qualification tests’ as a criterion for voting. Pass the test and you might be allowed to vote.

In my book The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World, I criticise Brennan and other self-proclaimed epistocrats for reviving outdated notions of aristocratic authoritarianism. I suggest their ideological background is worth looking at closely, because they represent an aspect of politics today that is less discussed than far-right populism, on the one hand, or growing worker unrest among people taking to the streets in France, Chile and Hong Kong, on the other. Many protestors in the streets want more representative government – more democracy – and this worries epistocrats, who want less.

The epistocratic attack on voting rights is coming from what might be called ‘the corporate centre,’ represented by centre-right thinkers who have spent decades waging quiet think-tank warfare against any policy they see as ‘socialist,’ including better pay for workers and more taxes on billionaires. Like Friedrich Hayek before them, epistocrats are reviving an anti-democratic strand of libertarianism that Hayek popularised later in life as he grew more disenchanted with democracy.

But what does all this have to do with John Stuart Mill?

Mill comes up frequently in debates about epistocracy because some epistocrats see him as their ideological ally. Mill is famous for suggesting that voting rights should be linked to education levels, and this point is leveraged today by epistocrats, who suggest that Mill too might be an anti-democratic if he had to live through Brexit. Their argument is not without appeal. But Mill was writing at a time when voting rights were, of course, far more restricted. The right to vote was linked to property ownership, a plutocratic system that he despised. Critical of what he called ‘aristocratic prejudice,’ Mill quite simply did not trust wealthy men to make good decisions for other people. Today’s epistocrats only trust wealthy men.

Mill’s dedication to expanding rather than limiting voting rights has been highlighted by Cambridge political theorist David Runciman, who is also critical of the idea of epistocracy. Runciman makes very good points about the authoritarian risks of epistocracy. But he also offers a curious suggestion: that ‘Epistocracy is flawed because of the second part of the word rather than the first – this is about power (kratos) as much as it is about knowledge (episteme).’ Runciman is right about the problem of power. It is deeply worrying that epistocrats are dancing openly with authoritarianism by calling for limits to voting rights. But it’s debatable to suggest that there’s less of a problem with the first half of the word: episteme, from the ancient Greek for ‘to know, to understand.’

Epistocracy isn’t simply flawed at the level of power; it’s also deeply flawed at the level of epistemology. It’s flawed because of the erroneous assumptions Brennan and others make about the nature of knowledge and the links between education and superior decision-making.

For example, in Against Democracy, Brennan offers the following flippant and spurious claim about voters in the United States, based on survey data: whites on average know more than blacks, people in the Northeast know more than people in the South, men know more than women, middle-aged people know more than the young or old, and high-income people know more than the poor…Most poor black women, as of right now at least, would fail even a mild voter qualification exam.

Because of their ‘lack’ of knowledge, Brennan thinks any voters who are more ‘ignorant’ – the poor, for example, and especially poor black women – should not be permitted to vote. And if they’re are upset about this, his answer is simple: they should ‘get over it or study more.’

Aside from being inherently unjust, anti-egalitarian and deeply vulnerable to different forms of racist, ageist and class-based discrimination, I suggest that Brennan makes a spurious claim because he assumes that voter surveys are a fair reflection of a person’s store of knowledge, when they are not. It’s also deeply procedurally flawed, because he and other epistocrats assume that people who pass ‘voter knowledge’ tests are inevitably superior at both political and moral reasoning.

John Stuart Mill would have seen the deep flaws in this. He was a fierce critic of the assumption that knowledge about one aspect of society would translate to sound decision-making in other areas. It’s an aspect of his writing that today’s epistocrats ignore. Yes, he wanted voting rights linked to education, but that’s because he hoped that educated groups of men and women could improve the political decisions of the rich. But he also wasn’t naïve about the highly educated. He saw their problem as well. It was a simple problem and yet it’s one that was under-acknowledged in his day, and it remains under-acknowledged today. Mill realised that smart people often tend to underestimate their own elite ignorance. This truth can be seen in a remark he made about Jeremy Bentham: ‘There is hardly anything in Bentham’s philosophy which is not true. The bad part of his writings is his resolute denial of all that he does not see, of all truths but those which he recognises.’

This problem was not Bentham’s alone; Mill saw it as a shared universal tendency: our tendency to deny what we don’t want to see. He once dryly put it this way: ‘In history, as in travelling, men usually see only what they already had in their minds.’

The problem of elite ignorance, or ‘aristocratic prejudice’ as Mill called it, has not gone today and in many ways it may be worse, revived by people such as Brennan who have heaped scorn on poor and uneducated voters for the Brexit outcome and for Donald Trump’s win.

Yes, education was a factor in both outcomes, with college-level degrees leading to more preference for ‘remain’ and less preference for Trump. But the jump from this to ‘let’s end democracy as we know it’ is a curious and more than a little dangerous leap of logic. For one thing, the epistocrat ‘solution’ to the problem – ‘voter qualification tests’ – can be easily manipulated to serve racist, self-serving interest groups. It has happened in the past, and quietly, similar efforts are happening today through indirect disenfranchisement, including deeply illiberal voter ID requirements.

The term ‘epistocracy’ may be new, but the anti-democratic current of libertarianism it represents is not. The only thing truly new is the way that epistocrats are airing their authoritarian attacks on democracy in the open. And why now? Because they have spied a way to exploit centrist fear over ‘populist’ support for Trump and Brexit. They’ve sensed a hook to seduce other ‘reasonable centrists’ to see the supposed anti-democratic light, and sadly, they’re not wrong. Far too easily, the episocrats are managing to ideologically freeride upon widespread Brexit anguish and concern – anguish that is equally felt by ‘leavers’ and ‘remainers’ today – to undermine democratic rights.

To combat this, defenders of democracy raise good points, including the most obvious rebuttal: if unequal education generates ‘voter ignorance,’ then we need to improve education inequalities, not dismantle democracy.

This is an important point, but a little paradoxically, there’s also a flaw with seeing education as the sole answer to so-called ‘voter ignorance.’ It’s a flaw that Mill understood. That problem is the way that education is not a guarantor of moral decision-making. Mill endlessly despaired about the way some of his most ‘educated’ peers supported US slavery. Mill himself was racist in his own attitude to India. He could not avoid the problem of his own elite ignorance, but at least he saw the problem: the way that elite ignorance can often be worse than lay ignorance because increased education generates false confidence about how much the well-educated actually know.

As I write in The Unknowers, the belief that poorer voters are inevitably more ‘ignorant’ than elite voters is a dangerous myth, leading poor citizens throughout numerous democratic crises in modern history to be blamed for electoral results that are often spearheaded and financed by wealthy interest groups.

To make this point clear, look at a key epistocratic proposal: ‘voter qualification tests.’ If such a test was introduced, a well-educated figure such as Steve Bannon is certainly going to pass. Trump would also pass it. Really, he would. Even if he failed the first couple of times, he would eventually take a break from golfing to ‘study more.’ But this doesn’t mean we’d be better off with more Bannons and Trumps in charge, especially as it’s harder to vote them out because democracy has been intentionally axed.

The best defence against anti-democratic epistocrats can be seen in their own writing. There, we can find examples of the same problem that Mill identified in Bentham: a refusal to recognise truths that don’t fit with earlier ideological positions. This problem can be seen in Brennan’s book Against Democracy. It is published by the venerable Princeton University Press. Despite getting through peer review, it’s inaccurate and one-sided in many places. It’s full of market fundamentalist ideological positions that are asserted as if they were timeless economic ‘facts.’ For example, Brennan is highly dismissive of any form of protectionist trade policies, which he lumps together as ‘mercantilism’. What Brennan doesn’t acknowledge is that both the US and Britain adopted highly protectionist policies while they were becoming economic powerhouses. Average Americans today who are sympathetic to economic protectionism may have a more robust and accurate understanding of UK and US economic history than Brennan’s book offers.

Brennan’s own selective, cherry-picking approach to economic theories is a microcosm of what’s wrong in general with ‘epistocracy.’ It’s the same problem that Mill saw: the way that educated and wealthy figures can be led by their status and education to misrecognise their own ignorance.

Does this mean that ‘lay’ voters are free of the same problem, of their own ignorance and blindspots? Of course not: all humans are more ignorant that they like to admit. We are all, as humans, opportunistically selective about evidence. But the great flaw of epistocracy is the dangerous and deeply irrational presumption that a particular group of ‘knowers’ are less prone to be misled by their own biases.

To update a remark made by Mill: when it comes to Brexit, just as with history and travelling, women and men tend to ‘see only what they already had in their minds.’ We need political systems which militate against this problem. We don’t need authoritarian political systems which compound it.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Linsey McGoey is professor of sociology and Director of the Centre for Economic Sociology and Innovation (CRESI), University of Essex. This essay is adapted from her book, The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World, out now.

This is a really interesting piece – thank you. I’ve read Brennan’s book and agree with your critique here.

I wonder if the libertarian argument for epistocracy is the dominant one though? I have encountered plenty of people on the Left also suggesting that ‘low information’ voters did not know what they were voting for, and even floating the idea of a knowledge voter qualification. This also feeds in to a stronger support for the EU which operates in a sort of semi epistocratic way via the downgraded parliament and upgraded role for lobby groups, NGOs and experts. Also witness the way some pro Remain liberals and people on the Left very readily interpreted the Brexit and Trump votes as attacks on expertise per se, often evidenced with reference to a single sentence from an interview with Michael Gove taken out of context, rather than a demand for control, democracy or sovereignty. The reflex of many, including many liberal academics, has not been to look at how to deepen democracy, but to double down on regarding voters as acting irrationally, against their own interests (often with the press implicated as duping the masses). They may not be making an argument for epistocracy, but are headed that way.

I know someone who works in the defence industry. His experience is that his company has to bid against French companies for contracts put out by the UK Government. However, his company has long since given up bidding for French defence contracts because experience has shown that it is waste of money and time. (Interestingly, they do also have to compete against American companies but they do win some bids in the US.) My acquaintance tells me that many in the defence industry see the EU as a stitch up and are pro Brexit. I mentioned this to someone working in the City and he said that the experience in his industry was different.

This is the point surely; democracy is the sum of everybody’s experience. If the majority of people have experience of the EU which they feel is detrimental and the minority find otherwise then the country would be strongly pro Brexit. If the reverse is true, then it would be strongly anti Brexit. It is the sum of the individual experiences and that is the strength of universal suffrage.

Many people enter politics to relieve poverty. The people who best understand poverty are the poor.

The UK had a form of epistocracy up to 1945, when graduates of certain universities got a second vote. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_constituency . It amazes me that anyone would revive this. Why not go the whole anti-Reform Act and bring back the rotten boroughs, public voting and voter bribery, and other devices that kept control of the House of Commons in the pockets of the Upper Ten Thousand?

Dear Remainers, by all means campaign for a Liberal Democrat government or for the UK to rejoin the EU. But please don’t try to abolish democracy. It’s not perfect, but the alternatives were tried and found wanting long ago.

Democracy is also a process. People have to goof and realise it as those poor people in Zimbabwe realised. That they were stuck with Mugabe for years (and Mngagwa) will only make them even more determined when finally they get a useful vote.

Much ink was spilt in Rhodesia in an effort to think of ways to qualify the vote (Africans had the vote of course under white rule providing they had 5 ‘O’ levels or a fat income) much as Brennan attempts to show.

Brexit will sharpen Britons’ political abilities far more than any number of courses.