For many advocates of a Brexit, the principle of ‘returning powers to Westminster’ is sacrosanct. They point out that parliamentary debate subjects legislation to proper domestic scrutiny in a way that is impossible in Brussels and Strasbourg. Yet, argues Thomas Winzen, Britain’s opt-outs and the considerable parliamentary time already devoted to EU-related questions suggest that the Commons is not being sidelined. In addition, should Britain vote to leave, the resulting trade deals and bilateral negotiations would be largely thrashed out behind the scenes. On balance, Brexit poses a greater threat to the Commons’ relevance than does a Remain vote.

For many advocates of a Brexit, the principle of ‘returning powers to Westminster’ is sacrosanct. They point out that parliamentary debate subjects legislation to proper domestic scrutiny in a way that is impossible in Brussels and Strasbourg. Yet, argues Thomas Winzen, Britain’s opt-outs and the considerable parliamentary time already devoted to EU-related questions suggest that the Commons is not being sidelined. In addition, should Britain vote to leave, the resulting trade deals and bilateral negotiations would be largely thrashed out behind the scenes. On balance, Brexit poses a greater threat to the Commons’ relevance than does a Remain vote.

Democratic politics, the parliamentary arena, and European integration

Let us first take a step back and recall what makes parliaments so important in democratic politics. The parliament is an arena for contestation between government and opposition. In all countries—especially in Britain—rules and conventions require the government to come to parliament in order to provide information and justification for its policies. These same rules allow the opposition to learn about and take a stance on the government’s choices. Simple as this process may seem, it has important consequences. The anticipation of parliamentary contestation means that government leaders will work to ensure robust backbench support. They, furthermore, have to be able to justify their policies with reference to some ‘general public interest’ that has traction among citizens and does not easily crumble under the preying eye of the opposition. Not least, ministers must keep tabs on the executive bureaucracy to ensure that they can stand by the proposals arising from their departments. Being aware that they will confront the government, the opposition likewise has incentives to carefully examine executive behaviour and formulate criticism that resonates with the electorate.

European integration has long been said to undermine democratic politics in the national parliament. Neither the government nor the opposition wants to debate matters effectively decided elsewhere. Moreover, the government can blame Brussels to avoid the need to justify its policies, and the difficulty to identify who exactly makes EU decisions renders it hard to challenge such a strategy. For the opposition, in turn, it is challenging to find out the details of government behaviour in distant European arenas, which further limits its ability to discover and expose weaknesses. In addition, any party debate in the context of EU affairs has a ‘constitutional dimension’. Critique and support of governmental policy regularly become mingled with systemic critique or support of the EU’s institutions and Britain’s membership. The main parties in Britain and other countries appear to gain little electorally from these debates and, therefore, may prefer to avoid parliamentary contestation over EU-related questions altogether. The result, many observers suggest, is that the parliament has lost relevance as an arena of democratic politics in areas under EU jurisdiction.

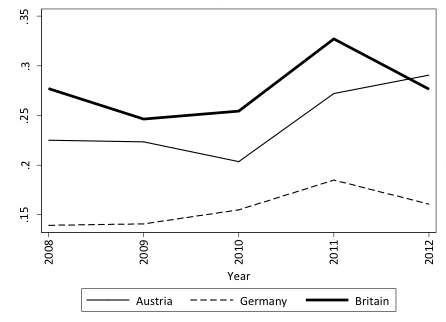

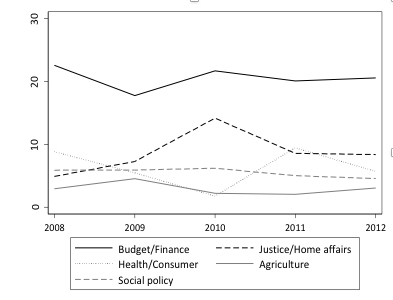

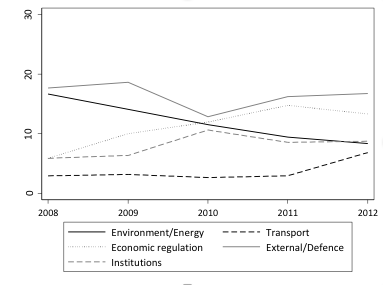

Nevertheless, it would be misleading to think that the British parliament never debates EU-related questions. Around 30 percent of its plenary debates between 2008 and 2012 entailed a strong EU dimension – far more than in Germany and slightly more than in Austria (Figure 1). Unsurprisingly, budget and finance policy questions, such as about banking regulation or macroeconomic strategy have dominated the plenary agenda. Topics related to economic regulation, such as the social rights of workers, have acquired greater prominence over time. Thus, even though European integration certainly constrains parliamentary politics, it is also inaccurate to say that the plenary has ceased to be relevant as an arena of open contestation. The possible referendum outcomes should be considered against this backdrop.

Figure 1. EU-related parliamentary debates in the House of Commons, 2008-2012

b) The relative importance of issue-areas in EU-related parliamentary debates in Britain

Sources: Data collected in the context of a research project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation in the context of the NCCR democracy.

Remain: a ‘status quo plus’ for the UK parliament

Should British citizens choose to remain in the EU, the deal made by the current government and the other member states will come into play. The implications of this outcome for the British parliament are limited, they amount to a ‘status quo plus’. First and foremost, the ‘Cameron deal’ is a clear endorsement of Britain’s differentiated membership in the Union. It does not only acknowledge that the country does not have to participate in the Eurozone and Justice and Home Affairs policies. It adds safeguards to ensure that this outsider status is unlikely to be eroded or rendered unsustainable in practice. With respect to the social rights of workers, Britain has secured further opportunities to opt-out, especially in response to a significant influx of workers from other member states. A Remain outcome will stabilise the constraints, but also the freedoms, that currently exist regarding parliamentary contestation in Britain.

Additionally, the settlement after a Remain vote would entail a ‘red card’ system: if 55 percent of the parliamentary chambers of the member states reject a proposed piece of EU legislation on the grounds that it violates the subsidiarity principle, the legislation will have to be changed or risk not being considered at all. This ‘red card’ system will not do any harm to any parliament but its positive effects are bound to be limited too. It is supposed to enhance the ‘influence’ of ‘national parliaments’, but what does this mean? Speaking of parliamentary influence is a ‘category mistake’. Influence is exercised by actors, but parliaments are arenas for political contestation. The ‘red card’ system might matter, but only in the rare event that the cabinet lacks the support of its parliamentary group. Even if this situation should arise, one may wonder whether the problem at stake would be about the subsidiarity principle, rather than about the substantive policy underlying an EU legislative proposal.

Finally, it is possible that a Remain vote will put at least a temporary end to principled debates over the desirability of membership that has dominated the British public sphere in recent years. Whether this is desirable, of course, lies in the eye of the beholder. One advantage, though, that scholars of parliamentary politics would highlight is that more room might emerge for media reporting on the policy-oriented debates that take place in the Commons, as Figure 1 makes clear. While tangible, systematic information on this matter would be desirable, it appears to be the case that much parliamentary debate on policy-making in the EU currently goes unreported. Settling the constitutional question might change this.

Brexit: the ‘sovereignty illusion’?

Social scientists never tire of saying that predictions are difficult, especially about the future. Unlike the Remain campaign, advocates of Brexit lack a well-defined scenario to put into practice after 23 June. The promise for the British parliament is that all the constraints on democratic contestation discussed early will cease to apply, together with the country’s EU membership. This hope, however, may prove illusory, in light of the experiences of Norway and Switzerland.

Before we come to these experiences, one should examine what Britain would really exit from. Which existing constraints for parliamentary contestation will cease to apply in the event of a Brexit? Keep in mind that the country, alongside Denmark, already enjoys the most far-reaching opt-outs from membership. The main area in which Britain participates fully is the common market, and flanking policies such as regarding the environment or consumer protection. Market access, however, is what even many Brexit advocates would want to retain after membership. It is currently hard to specify the policy domains that Brexit would open up for parliamentary contestation.

At face value, EU market membership may seem to constrain parliamentary contestation over the economy. Yet one should entertain the possibility that any limits to contestation observed actually result from changes in party politics, notably Labour’s ‘Third Way’ transformation in the 1990s and 2000s. Under the leadership of Tony Blair, the Labour party endorsed policies of international economic integration and domestic welfare restraint. It converged towards economic-liberal points of view and, in this way, narrowed party disagreement on the economy. This shrinking disagreement, more than EU membership, may have reduced the scope for and relevance of the parliament as an arena for the contestation of economic policy. No doubt, there is much scholarly disagreement on this diagnosis. The point, however, is that Brexit may have less of an effect on parliamentary contestation than one may think at first sight.

Finally, what will define the British relationship with the EU after membership? It stands to reason that the government will likely seek a bargain that secures continuous access to goods and services markets. The EU will likely insist that such a deal requires participation in the free movement of workers and any flanking policies, as it does in the case of the European Economic Area and in its bilateral relations with Switzerland. It is not clear at this stage whether Britain would seek a deal similar to the EEA or to Swiss-EU bilateral relations or another outcome, but it is clear that lengthy technical negotiations will ensue. Moreover, the experience of Norway and Switzerland is that the management of market access is a highly technical process dominated by civil servants and by the imperative to retain compatible regulatory frameworks and market access. Thus, instead of the parliament becoming a more relevant arena for contestation than before, decisions over economic regulation and policy may become the domain of sectoral policy specialists and civil servants who will negotiate, implement, and maintain access to EU markets. The point of reference for the activities of the civil servants would be laws adopted by the EU without the British government having a say.

In conclusion, the Cameron deal enables us to identify the implications of a Remain vote relatively clearly. For the British parliament, remaining in the EU amounts to a ‘status quo plus’. However, the benefits have more to do with the consolidation of existing British opt-outs than the ‘red card’ system. The consequences of Brexit are largely uncertain. Yet the hope that more room for parliamentary contestation over the economy would ensue is likely to prove illusory in light of domestic changes in party politics and the experience of other countries. If the goal is to protect the relevance of the parliament as an arena for democratic politics, Remain appears to be the better outcome.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of BrexitVote, nor the LSE.

Thomas Winzen is a post-doctoral researcher in the European Politics Group at the Center for Comparative and International Studies, ETH Zurich.

Well Thomas, you certainly like a challenge.

You will never manage to persuade anyone with that argument.

As a confirmed “Brexit” man I will not even bother to challenge you except to observe that “democracy” did not loom large in your article.

Why is it a common thread among brexit supporters that you won’t bother to provide an argument…

Gerry:

We cannot argue with those that “suport the EU” but refuse to take on board the elephant in the room of the euro-zone which has taken over the EU.

We will always be on the outside & we will always be left out of the loop. Not to accept that glaring fact is worrying.

Think a little more & little deeper.

Yeah, right. I was operating under the obviously mistaken belief that Parliament represented the people of the nation. It is good to know that a Parliament rubber-stamping the edicts of the unelected EU bureaucracy, some of whom do indeed come from the UK, albeit not actually being elected by the citizenry of the UK, is the proper role that we should wish for ourselves, and not this messy representing the voice of the people stuff we used to believe in.

OK so the EU doesn’t weaken parliamentary democracy but, rather, that parliamentary democracy is weakened by Britain’s membership of the EU. Our parliamentarians would rather take their orders from Brussels than listen to the people who elected them, the British electorate. It is pretty self-serving and true that our progressive modernising politicians, for that’s how they see themselves, are wedded to the idea of ‘collective responsibility and job sharing’ where they can be relieved of most of the important decision-making or, at least, blame Brussels when it suits. Then when it’s time to move on from Westminster, there’s Brussels waiting to reward them.

Unfortunately, we don’t elect the bureaucrats at the European Commission who tell our politicians what to do. The EU is a travesty of democracy.