With Remain’s lead steadily dwindling in the polls, Matthew Goodwin says both sides have everything to play for – particularly given the likelihood that older people will turn out in greater numbers than the young. He explains that poll experts are still uncertain about why phone and online polls are producing different results, and casts doubt on the belief that Remain will enjoy a surge in support as 23 June approaches.

With Remain’s lead steadily dwindling in the polls, Matthew Goodwin says both sides have everything to play for – particularly given the likelihood that older people will turn out in greater numbers than the young. He explains that poll experts are still uncertain about why phone and online polls are producing different results, and casts doubt on the belief that Remain will enjoy a surge in support as 23 June approaches.

There are only 75 days to go until the British people decide whether or not to continue their membership of the European Union. Since I last wrote, the race has tightened. According to the authoritative ‘Poll of Polls‘, it really is a dead heat – once you exclude undecided voters both camps are on 50%. This is quite a change from back in December and January when Remain often enjoyed a lead of 10 points.

It is worth noting that in the telephone polls, which have traditionally given Remain a comfortable lead, the gap has been closing. In the regular Ipsos-MORI tracker, for example, Remain’s lead has steadily declined from 44 points in June 2015, to 26 points in December 2015, 19 points in January 2016 and to just 8 points in the latest edition. In polls by ComRes too, also conducted by telephone, long gone are the days when Remain commanded a 27 point lead, as they did around the time of the 2015 general election. Since then Remain’s lead has fallen to 19 points in September 2015, 18 points in January 2016 and to 8 points in the latest (March) wave. Remain is still ahead in most polls, but its lead appears to have narrowed.

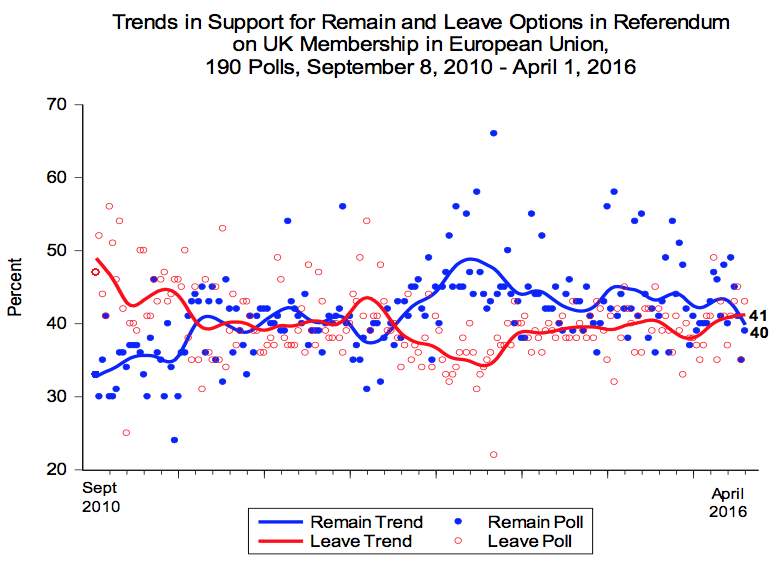

That the race has tightened is reflected in the chart below. Compiled by my colleague Harold Clarke, it is based on nearly 200 online and telephone polls between September 2015 and April 2016. It reinforces the point that there is everything to play for. Across all polls since March 1 Remain has averaged 43.8%, Leave 40.9% and the Undecideds 15.2%. Given that British society is highly polarised on the question of EU membership, with support for Remain and Leave anchored in very different social groups, it is unlikely in my view that we will now see dramatic change in the underlying trend. But, hey, academics have been wrong before!

How accurate are the polls? In recent weeks this question has triggered a lively debate. In a nutshell, some suggest that online polls, which tend to suggest that the race is currently very close, overstate support for Brexit. In part, it is argued, this is because online polls provide an explicit ‘don’t know’ option, allowing some voters to ‘hide’ their real views. In phone polls, which often do not include a don’t know option, support for Remain tends to be higher in theory because voters who would otherwise say ‘don’t know’, when forced to make a decision, lean instinctively toward Remain. Undecided voters are mainly closet Remainers, so the thinking goes.

At the same time, it is suggested that online polls may be failing to capture ‘harder to reach’ citizens who might be more socially liberal in outlook and hence more likely to vote Remain. Once the liberal views of harder-to-reach people are taken into account, Remain’s position in online polls improves by around 3 points but weakens in phone polls by around 5 points (which it is suggested might currently be relying on samples that are a bit too liberal) So, in short, the argument is that the ‘real picture’ might lie somewhere between the online and phone polls, but closer to phone, suggesting that Remain might still be a few points ahead.

Not everybody agrees with this take, however. Other analysts point out how the percentage of undecided voters is not always higher in online polls and that in cases where this option has been excluded the result has not always been higher support for Remain. Moreover, while it is worth remembering that undecided voters might not actually turn out to vote, it is also useful to highlight that in a few cases where pollsters tried to investigate the ‘real’ views of undecided voters, they did not find that they moved overwhelmingly to Remain. Other critics contend that social norms might be at work – namely that while people may be telling phone pollsters or face-to-face interviewers that they are socially liberal they might actually only be doing so because this is seen as ‘the right thing to do’. This debate will continue until and beyond the referendum in June. What remains clear is that we should continue to treat all polls with a healthy dose of caution.

We also have new evidence that challenges some other assumptions about the vote. One fairly widespread belief that you often hear at events is that there will be a late and sharp upsurge of support for Remain. After reviewing voting patterns at referendums across the globe, including ones on EU issues, the research (which I summarise here) suggested that for EU referendums this effect may be overstated or, perhaps, might not exist at all (a point underscored by the result of the Dutch referendum… as well as past referendums in Ireland, Denmark and France where it was the anti-EU option that gathered momentum as polling day approached).

The question of turnout has also continued to attract interest, not least from David Cameron, who has been pitching directly to those younger and typically more pro-EU voters. There is a growing body of research on how turnout could play a key role. In one recent poll the Brexiteers were ahead by two points but once intention to vote had been taken into account their lead extended to seven points. A recent survey by BMG and the Electoral Reform Society underscores the point. It suggests that whereas 21% of 18-24 year olds are “very interested” in the vote, the equivalent figure among pensioners who lean more heavily toward Brexit is 47%. Meanwhile, though only 44% of younger Britons said they are certain to vote this was dwarfed by the equivalent figure of 76% among older Britons. These findings add to those that we have discussed in these bulletins. And they point to a clear conclusion: while Brexiteers will want to explore ways of targeting and mobilising older voters, the Remain camp should be devoting significant effort to ensuring that younger Britons and middle-class progressives actually get to the ballot box.

Further reading

What comes after UKIP? A look at a not-so-secret plan among some Eurosceptics

A new experiment on the role of economic incentives in mobilising voters

Would the Norway model work? A closer look at the Norway-EU model

This post represents the views of the author and not those of BrexitVote, nor the LSE.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent, and Associate Fellow at Chatham House. He is also a senior fellow at the UK in a Changing Europe project. His most recent book is the co-authored Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain (2014). @GoodwinMJ You can subscribe to further updates from him here.