Once Britain loses its representatives in EU institutions, British stakeholders – both public and private – will have to find new channels of influencing European policy, as the decisions made in Brussels will continue to have a substantial impact on Britain’s interests. This analysis, by Andrei Goldis and Doru Frantescu, maps the most likely coalition partners that the UK-based interest groups can work with. Notably, these potential partners are different in the Council and the European Parliament.

Once Britain loses its representatives in EU institutions, British stakeholders – both public and private – will have to find new channels of influencing European policy, as the decisions made in Brussels will continue to have a substantial impact on Britain’s interests. This analysis, by Andrei Goldis and Doru Frantescu, maps the most likely coalition partners that the UK-based interest groups can work with. Notably, these potential partners are different in the Council and the European Parliament.

What are the Brits losing after leaving the EU institutions?

After Brexit, Britain’s empty seat at the decision-making table will deliver a significant blow to British political, economic and commercial stakeholders: while their activities will still be impacted by what is being decided in the EU, they will have lost their preferred and natural channels of influencing Brussels, ie. through British representatives in the EU institutions. As the UK’s chancellor of the exchequer Philip Hammond put it, the UK’s views will carry little weight in Brussels from now on.

VoteWatch Europe has previously shown that the UK was increasingly outvoted in the Council in recent years, thereby predicting the British government’s leap towards isolationism in the EU over the past years. Moreover, the UK also seems to have diminished its influence in the European Parliament in recent years, as a result of self-distancing of some of its own party delegations from the EU’s mainstream political families, as well as due to the results of the latest EU elections in the UK, where Euroscepticism triumphed.

Nonetheless, the British influence in the EU has been very significant in areas where British officials felt strongly about, such as financial services, the most important area of its economy. UK Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) have captured many powerful agenda-setting positions, such as rapporteurships of key EU legislation and EP committee chairmanships. For instance, UK MEPs have held the chairmanship of the Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection over the last three Parliamentary terms. Currently, a British Labour, Claude Moraes, is chairing the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, which deals with issues concerning data protection, migration and security. The Conservative MEP Timothy Kirkhope (ECR) was the rapporteur on the use of Passenger Name Records for the prevention of crimes, whereas Ian Duncan (ECR) was the rapporteur on a file reforming the ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme).

Furthermore, a report of an independent panel chaired by Lord Hannay of Chiswick in 2015 entitled The British Influence Scorecard – set up to discover whether Britain is a leader or a loser in Europe – found that the UK was “on track” to win up to 90% of its policy goals. Covering the policies examined in the Government’s Balance of Competences Review, the report shows that Britain was successful in 18 areas, did well in 20 more and was losing only in four.

Upon Brexit, the UK will lose both its seat in the EU Council and its Members of the European Parliament. So the British will have to find alternative political channels through which to make their voice heard.

Note: the UK will also lose its political Member of the EU Executive, ie. its European Commissioner. While the European Commission has committed not to fire the EU civil servants who hold British citizenship, these cannot be considered as channels of promoting specific (national) interests, due to their status as bureaucrats employed by the EU.

Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark are the best partners in the EU Council of Ministers

VoteWatch has shown that in the Brexit aftermath, France and Italy seem best positioned to hold the keys for the success of legislative proposals in the Council. However, by comparing Britain’s past voting records with those of France and Italy, we can see that they have been diverging on major policy issues. Germany has been seen as one of the main supporters of UK staying in the Union, due to similar views on internal market and security issues. However, the Germans have different views than the Brits on many issues, including freedom of movement of people and the economic integration of the continent.

On the contrary, the voting behaviour data shows that Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark have been Britain’s closest allies in the Council and these three governments seem to represent the natural first destinations for the continued lobbying and communications efforts of British stakeholders following Brexit. The positions of the British government have received backing from these countries on several important issues including internal market, transport, environment, foreign policy and foreign aid.

Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark are also the main promoters of decreasing the regulatory burden for EU businesses and for having stronger protection of copyrights. These pro-business member states will lose a key ally upon Brexit. As shown by the latest VoteWatch Europe’s report on the future equilibrium of powers in the Council, these three countries are not the strongest coalition builders in the Council, ie. they find themselves in minority more often than other member states (especially the Netherlands). This means that, depending on the policy area considered, UK-reliant stakeholders will need to target also other countries in the Council in order to ensure a positive outcome for their advocacy activity.

The European Parliament will be an increasing challenge

In the absence of a clear role in the Brexit negotiations that the Council will lead, it is likely that some British MEPs will lose their committee posts and other roles in the mid-term reshuffle, due at the end of 2016 / January 2017. The Parliament as a whole will shift to the left on the economic dimension, after the departure of its strongest anti-regulatory delegation.

The anticipated trend is that political parties within the Parliament will consolidate around the existing power blocks of the EPP, ALDE and S&D, with the EPP incorporating what will remain of the Tory-led ECR, whilst the UKIP-led EFDD might dissolve itself in light of its own success, allowing for a realignment of anti-EU MEPs, possibly around Marine Le Pen’s ENF.

It seems the current tendency towards grand-coalition solutions and sometimes backroom deals will go on, and the German perspective will remain the most influential force in the Parliament, by virtue of its strong position in both the EPP and the S&D.

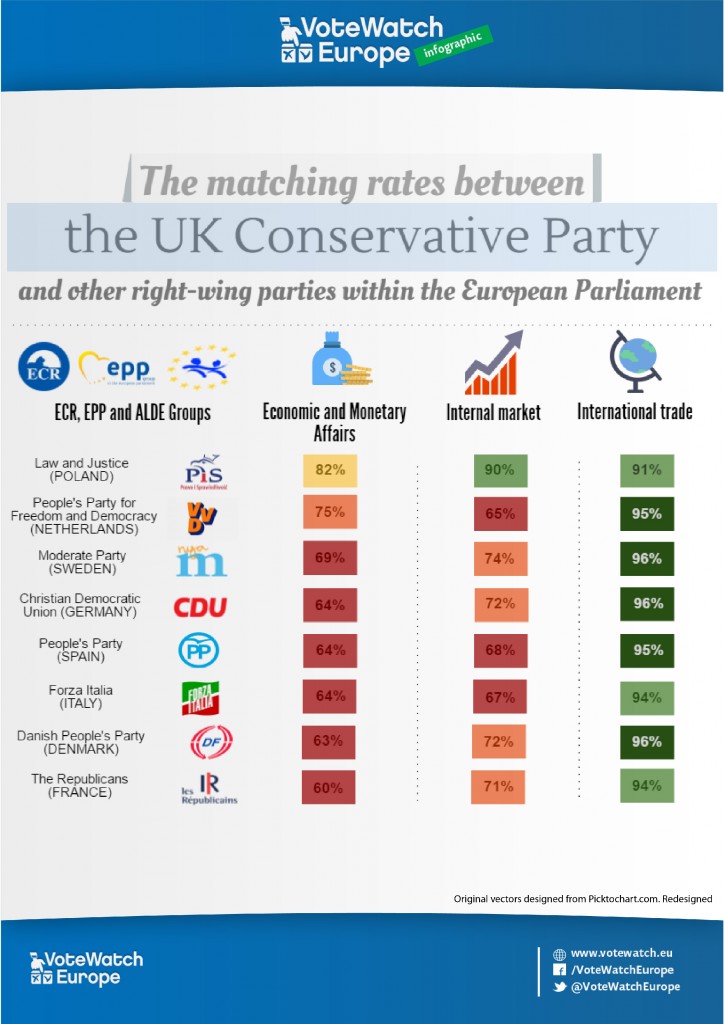

In order to find the next best partners for those who so far were relying on the UK Conservative Party to fight for their interests in the European Parliament, we compared the voting records of the British Tories with the ones of 8 other centre-right wing parties, selected on the basis of ideological affinity, size and geographical location. Two of them are members of ECR (Law and Justice and Danish People’s Party), five are members of the EPP and one party, the Dutch People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, is a member of ALDE (the liberal-conservative attitude of the party implies that the Tories are closer to it than to the centrist Christian Democratic Appeal).

As shown by the infographics, the matching rates differ considerably across the policy areas. In the EP, ideology plays a more important role than in the Council, as the parliamentarians are much freer to vote according to their own views. Not surprisingly, the Polish Conservatives of Law and Justice are the closest ally of the British Tories in the EP when it comes to the internal market and economic affairs. As regards international trade issues (such as TTIP, CETA), the German and Scandinavian centre-right parties are the closest partners.

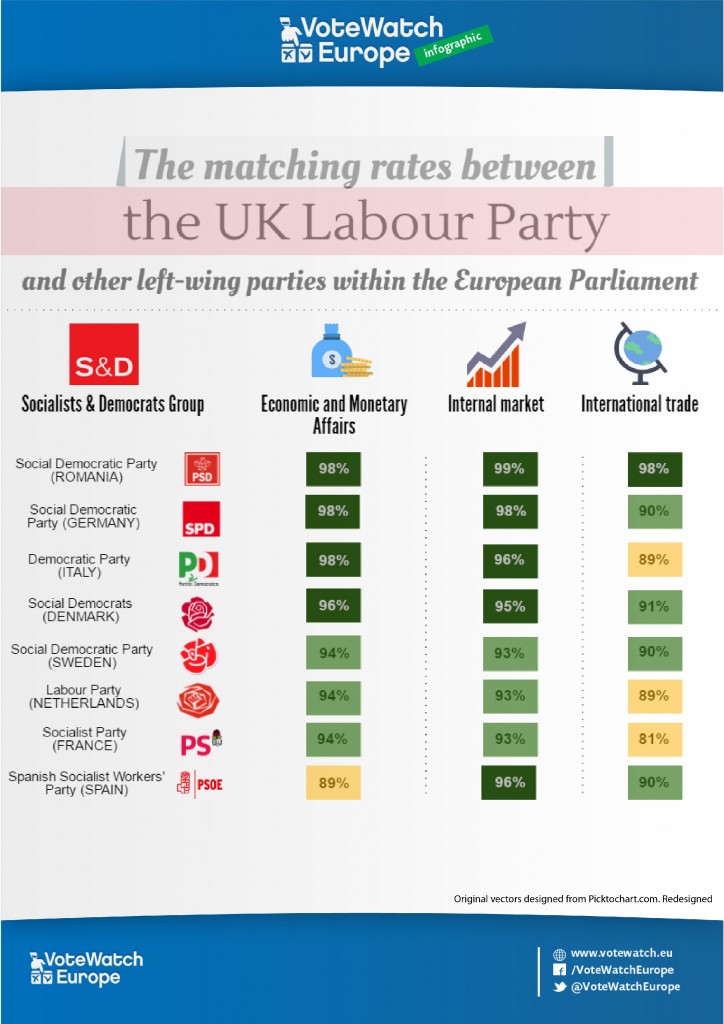

How about those promoting their views through the Labour party network? We used the same criteria to compare the voting records of the UK’s Labour party with eight other centre-left parties, all members of S&D.

Interestingly, among the parties considered, the Romanians in S&D are the closest ally of the Labour party in all the three policy sectors considered. The fact that the highest matching rates of the two UK’s largest parties (Tories and Labour) are observed with parties from Eastern and Central Europe also highlights the liberal and pro-business attitude of the MEPs from former communist countries. These MEPs might become in the future the new champions of the stakeholders currently directing their advocacy actions through the UK’s representatives in the EP. Interestingly, UK’s Labour party is closer to its German and Italian partners than to the Swedish and Dutch ones (which indicates that the best partners in the Parliament may be different than those in the Council and that these should be looked for on a case by case basis).

Conclusion

For these reasons, we expect a surge in the number of communications and advocacy initiatives coming from the UK to be redirected through the next best channels of influence. These are likely to be the Swedish, Dutch and Danish representatives in the Council, while in the EP the picture is more diverse: the Eastern and Central Europeans, the centre-right Swedish and Dutch parties, as well as the centre-left Italian and German parties. What remains to be seen is whether these representatives will be receptive to the claims and concerns of British stakeholders.

This post originally appeared on VoteWatch Europe and it represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog or the LSE.

Andrei Goldis is project consultant at APCO Worldwide London.

Doru Frantescu is co-founder and director of VoteWatch Europe (the Brussels-based think tank most followed by MEPs in 2016).