Brexit can’t simply be written off as a protest vote by worse-off, older and less educated voters, writes Piers Ludlow. Plenty of the so-called ‘liberal metropolitan elite’ – politicians like Boris Johnson, business leaders and journalists – also called for Britain to leave the EU. The dwindling number of pro-Europeans testifies to growing disillusionment with the European Union among the UK political elite.

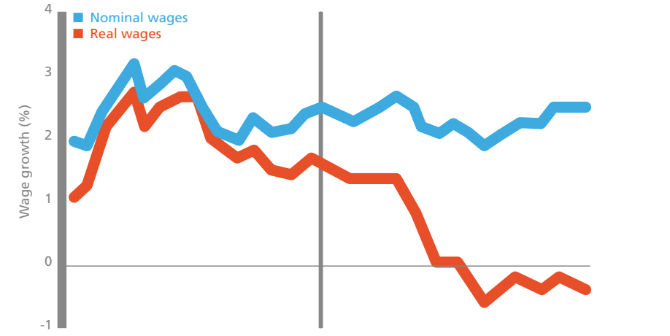

A great deal of the post-referendum analysis focused on the geographical, socio-economic and demographic divide between the typical ‘leave’ voter and those who voted ‘remain’. We have thus learned that support for Leave was disproportionately rural rather than urban, poorer, less educated, older and less liberal, than the 48% who opted for ‘remain’. This is important information, with serious implications for present and future governments as they seek to re-connect with, and assuage the fears of, those who feel marginalised, alienated, and hurt by globalisation, immigration, and other 21st-century economic realities.

These findings can also have the effect, intentional or unintentional, of absolving large parts of the educated, liberal and cosmopolitan elite from the referendum’s outcome. Brexit becomes something that was done to ‘us’, by another Britain, whose values, attitudes and world-views are utterly different from ‘our’ own. This is a very human reaction. It mirrors the tactics adopted by most liberal Americans during the George W. Bush presidency, or educated Italians while Silvio Berlusconi ruled their country. But it is seriously misleading. For there were at least three ways in which Britain’s political elite, including many of those who voted remain, played their part in the electoral outcome.

The first and most obvious centres on the number of mainstream figures who joined the Leave campaign. In marked contrast to 1975, the referendum of 2016 was not a tussle between, on one side, a bizarre alliance of extremists, notable for the general wildness of their views, and a solid phalanx of ‘respectable’ opinion leaders on the other. Instead, there were a significant number of mainstream politicians campaigning for Brexit, flanked by a vocal minority of business leaders, journalists, and even the occasional academic. Theirs may have been a dissident view, but it was a dissident view no longer confined to the fringes of British politics but instead regarded as being within the parameters of normal opinion. Partly as a result, far fewer corporate entities, from businesses to universities via the Church of England, felt able to take the unambiguously pro-European stand they had in 1975.

Second was the all but total disappearance from the British political landscape of out-and-out pro-Europeans. In 1975 Harold Wilson had been able to play a role in the referendum campaign to which David Cameron would have been eminently suited, namely that of the mild sceptic, uncertain as to whether ‘Europe’ was a good thing or not, but ultimately swayed into the ‘yes’ camp by a combination of the renegotiation deal he had been able to secure and the weight of the ‘yes’ arguments.

He could play this fence-sitting role, since the pro-European case could be left to pro-Europeans like Edward Heath, Roy Jenkins, Willie Whitelaw or Shirley Williams. And as a fence-sitter who ultimately decided that it was safer to stay in, his views chimed with those of much of the British public and helped convince many others who were unsure into casting their votes for the ‘yes’ side. But in 2016 Cameron was unable to replicate this strategy given the absence of prominent pro-Europeans on whom he could rely.

The pro-European wing of the Conservative Party had all but vanished, Labour pro-Europeans were in disarray and stymied by a party leader with little sympathy for their cause, and the Lib Dems had been virtually wiped out by the 2015 election result. It was thus up to the Prime Minister and George Osborne to articulate the pro-EU case. And their credibility in doing so was always bound to be limited. This was the same Prime Minister who only a few years earlier had seemingly relished his role in blocking an EU deal designed to resolve the Euro crisis, and had pointedly stayed away from the ceremony at which the EU had been given the Nobel Peace prize in 2012. And if he really did believe that the EU and British membership in it was fundamental to European peace and security as was claimed in one of his campaign speeches, why was he putting peace and security at risk by holding a referendum on the issue in the first place?

Third, and much more insidious, was the way in which large swathes of the British political elite, including many who would ultimately advocate ‘Remain’ and who have professed great regret at the outcome of the referendum, had been highly critical of the EU over much of the preceding decade and a half. Like any political system, the EU is an entirely legitimate target for close political scrutiny and critique. Furthermore, the succession of crises that have beset the EU since the turn of the century gave would-be critics in parliament, in the media and elsewhere plentiful ammunition. But so relentless had been the barrage of criticism, with little space devoted by contrast to the many aspects of European integration that continued to work well, or to those parts of Europe which rode out the aftermath of the 2007 economic crisis rather more successfully than did the UK, that it substantially weakened the terrain on which the pro-Remain battle needed to be fought.

After all, if the EU really was a deeply flawed and undemocratic entity, liable imminently to collapse under the combined effects of the ‘failed’ single currency and its inability to control migration, then Britain was surely better off deserting it – and perhaps in the process leading others away from the disaster also? And given such a background, was there any wonder then that the multiplicity of statistics produced by Remainers purporting to demonstrate the extent to which British economic prosperity was inextricably tied up with continued EU membership failed to gain much traction with the wider public?

Taken together all three of these points do rather underline that the referendum outcome was not just a rebellion by those who the British political system had traditionally marginalised. Instead it was an electoral verdict rooted as much in the ambivalence about European integration felt by Britain’s political elite, as it was in the anger of those who had done poorly out of globalisation, who resented the way in which Britain was changing, and who were scared by immigration. As such, understanding what happened will also involve the liberal elite looking itself in the mirror rather than simply attributing the outcome to another Britain of which they were barely aware.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It was first published at The UK in a Changing Europe.

The Remain vote was Scots and academics, posh women and their product: students

The Scots voted Remain because they need the security of an EEC like body to give them a hand out if independence goes wrong. Paradoxically they were voting Remain for the same reason as the English voted Leave: self government.

Apart from the confused Scots we have arrogant academics. Academics, as we all know, are vain and self interested. They see the EU as extended pastures where they can graze for employment. They don’t give a damn about people who are immobile because they weren’t able to “escape poverty through education”. Those left behind who are bound to a locality are “xenophobic morons”.

Of course, Remain voters comfort themselves with holy macroeconomic ideals for ending poverty etc. etc. but consider microeconomics beneath them and probably racist. In fact anyone who gets in the way of their career is likely a racist.