The Common Agricultural Policy has long been resented by many in the UK, even though Britain’s rebate has cut Britain’s contribution and a succession of reforms mean it is far less inefficient. In an edited extract from a new report for the Centre for Policy Studies, Richard Packer argues that the government will probably want to pursue a similar system of farm subsidies after Brexit, although it does have the opportunity to adopt different priorities – especially if it decides to grow GM crops.

The CAP was – and perhaps still is, at least in Britain – probably the least-loved of EU policies. In the minds of public and media alike it has always been associated with so-called butter mountains and wine lakes, with high cost and waste, with high consumer prices and with ‘export refunds’ which allegedly ruined farmers in developing countries.

There was and is much to criticise about the CAP, though the caricature is less than fair. The butter mountains, wine lakes and export refunds are all long gone. As is only to be expected, the nature of the CAP reflects real economic and political pressures placed on democratically elected politicians. It is not unknown for UK ministers to adopt economically imperfect policies faced with the same level of political pressure. But the negative views of the CAP consistently held across the UK political spectrum since UK accession – that is for over 43 years – undoubtedly contributed to the jaundiced national view of the EU as a whole and, ultimately, to the Brexit vote.

Though the criticisms of it are in some respects overstated, the CAP is ill-suited to UK circumstances and the fact that its rules will cease to apply here is a good thing. In particular, the much larger agricultural sectors in many other EU member states make it very costly for the UK, because of the EU common financing rules. Much of the UK financial contribution to the EU, which gave rise to the need for a UK rebate, came in effect from UK contributions to agriculture in other member states.

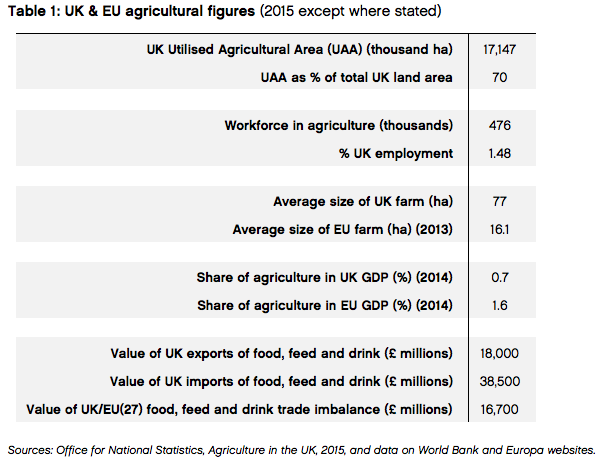

Table 1 illustrates UK agriculture compared to agriculture in other EU member states and relative to the UK economy as a whole. It shows that agriculture is less important to the UK economy than to the economies of other countries in the EU. This explains much of the difference in attitudes demonstrated by UK and other EU ministers over the years. Their objective interests are different.

When the UK joined the Community in 1973, the Treaty of Rome did not require there to be a common Community agricultural policy. An alternative approach of coordinating national policies was also explicitly allowed. However, the establishment of a common policy had been favoured by vocal parties, especially in France, which stood to gain a lot from common financing rules.

Accordingly, common policies had been agreed for the main agricultural commodities in the 1960s, and by 1973 the CAP was well established and aspiring members had to accept it. When the UK first joined the CAP in 1973, the policy was notorious for its expense, high consumer prices, excessive intervention, variable import levies and export refunds. It had very high consumer and financial costs, was regarded as a triumph of European co-operation by the Six and as an abomination by most of the rest of the world. This is the CAP which many people remember. It has been extensively modified over the past 43 years, and many of the policy instruments that characterised it before and after 1973 – such as intervention buying, import levies and export refunds – have now effectively disappeared.

Post-Brexit, the UK will have the opportunity, if desired, to develop a completely different agricultural policy – though with the proviso that to meet WTO obligations overall government support to UK industry, as expressed in Producer Support Estimate calculations, should not rise.

Agricultural policy should have these attributes:

- the encouragement of an efficient agricultural sector which contributes to national prosperity;

- a policy which costs no more than the present one, as measured both by PSE (which captures both financial and consumer costs together and is the terms in which WTO commitments are defined) and, separately, in financial terms;

- one which contributes to environmental aims in terms of both landscape and biodiversity;

- one which meets consumers’ needs, through the availability of nutritious food at reasonable prices;

- one which minimises bureaucracy and administrative expenditure by all parties.

Do these desired attributes point to the need for a major policy change? It might seem puzzling, but despite the CAP’s longstanding reputation, the objectives listed are best pursued by something that is fundamentally similar to the present policy – that is, a system of support, including area payments to farmers. This is because the CAP has had many of the inefficiencies on which it built its early reputation reformed away.

Furthermore, after Brexit it looks fairly certain the UK will only be paying for UK agriculture, not for agriculture in other countries. Given the turmoil that would be faced by British farmers if the CAP were radically altered in negotiations, there is no great pressure from any quarter for major change.

The administrative structure to support the present system is already in place, and building a new one would incur significant cost. All this is compatible with the statement made by the Chancellor in August 2016 that existing payments in certain areas, including agriculture, would continue until at least 2020. I recommend they should continue, no doubt with modifications here and there, for a lot longer.

There is no need to specify exactly what changes there might need to be after Brexit, but two areas stand out for examination. The first is the bureaucracy and complexity of the present payment system. Many claim that this could be significantly simplified with no loss of rigour. With billions of pounds of public money at stake, there must be proper accountability.

The second concerns the level of area payments. Some statement of government policy will be needed so that farmers can plan ahead.

If the UK were outside the full single market, then post-Brexit UK national rules would apply in policy areas such as plant and animal health and GM foods. UK advisory committees would need expanding and/or re-establishing. Sometimes this could be an advantage: for example, the EU debate on GM foods was for a considerable period hijacked by anti-scientific forces. If, as many believe, GM has a significant role to play in meeting future food supply sustainability, it would be sensible to make rapid progress for the benefit of future generations. Some groups in the UK are opposed to GM as a matter of principle. But it is to be hoped the scientific view would prevail, and there would be an opportunity to ensure it did.

This is an edited extract from Richard Packer’s report for the Centre for Policy Studies, Brexit, Agriculture and Agricultural Policy. It represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Sir Richard Packer was a career civil servant mostly at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF). As a junior official he worked on the Wilson (1967) and Heath (1970-72) bids to enter the Common Market. He was subsequently seconded as first secretary at the UK Permanent Representation in Brussels (1973-76). He was Permanent Secretary 1993-2000.