Older Britons were far more likely to vote Leave than 18-24 year-olds. Will Thomas looks at attitudes to the EU since we joined in 1973. Until the mid-1980s, the young and old shared relatively similar support for the EU – but then their views began to diverge. He suggests that young people are in a better position to take advantage of the EU offers than the old are.

Older Britons were far more likely to vote Leave than 18-24 year-olds. Will Thomas looks at attitudes to the EU since we joined in 1973. Until the mid-1980s, the young and old shared relatively similar support for the EU – but then their views began to diverge. He suggests that young people are in a better position to take advantage of the EU offers than the old are.

One of the big talking points in the days after the EU referendum was the difference in voting behaviour between the youngest members of the British electorate and the oldest. Indeed, according to Lord Ashcroft’s poll of over 12,000 voters on referendum day, Britons aged 65 and over voted 60 per cent in favour of leaving the EU, whereas the figure for 18-24 year olds was only 27 per cent.

However, while the media and much of the political discussion following the referendum explicitly addressed the generational split in British public opinion towards Europe, very few commentators have tried to answer a number of the central questions concerning this difference. For example, why does this age gap exist? Has it always been there? If not, how recently has it developed? And why are younger Britons seemingly more pro-European than their elder compatriots?

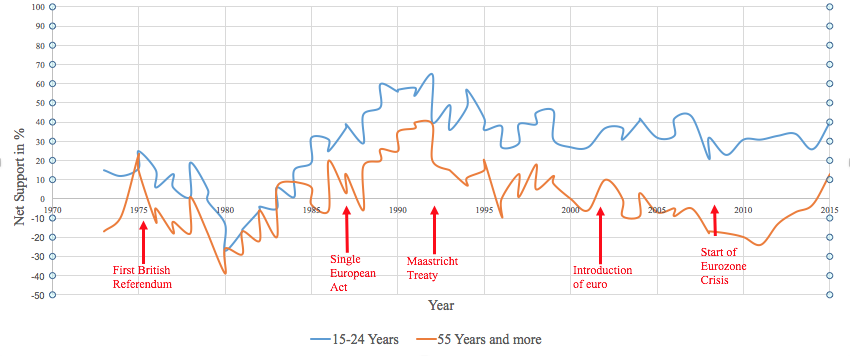

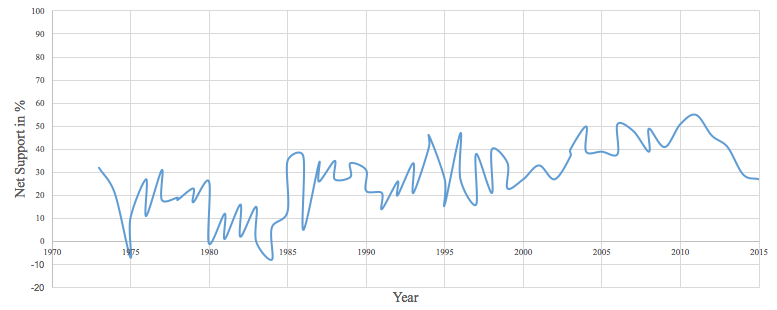

With these unanswered questions in mind, I attempted to chart the role that age has played on British public opinion toward the EU since the United Kingdom joined the European Community in 1973. Through analysis of Eurobarometer opinion polls – a biannually conducted survey conducted in each of Europe’s member states – levels of support for the EU among various age groups in the UK can be examined over an extended period of time.

For example, my research compares and contrasts the views held by two age-based extremes of British society: Britons aged 15-24, and Britons aged 55 and over. In order to comparatively analyse the opinions of the two age groups, I analysed a recurrent Eurobarometer question asking respondents to assess if the UK’s European membership is a ‘good thing’, a ‘bad thing’ or ‘neither good nor bad’. A figure of ‘net support’ was formed by subtracting the percentage who claimed Britain’s membership was a ‘bad thing’ from those who though it a ‘good thing’.

While British public opinion toward the EU among both age groups was unlikely to remain consistent, and indeed to be in a state of regular fluctuation – particularly when changing political and economic circumstances are taken into consideration – the analysis highlights that for much of Britain’s European membership, there is an observable trend for younger members of the British electorate to view the EU more favourably than their older compatriots.

Indeed, in many ways the development of opinion among the two different age groups can be separated into two distinct phases; before and after Eurobarometer 22 in October 1984. In the first decade of the UK’s European membership, it is noticeable the two age groups’ levels of support are strikingly similar, with both seemingly inclined toward Euroscepticism. However, 1984 marks a significant positive shift in the younger group’s public opinion that is never replicated by the older cohort. From this point onward the younger age group maintain a considerably higher level of support for the EU in comparison with the older age group. Interestingly, there is also a trend for this gap in support between the two age groups to remain relatively consistent over the last thirty years of Britain’s European membership.

So why have younger Britons been consistently more likely to view European membership more positively than older Britons? An interesting strand of recent literature contends that globalisation and the process of European integration have created a bipolar division in many Western European societies. For instance, some claim that the citizens best positioned to take advantage of developments in the global economy – or the ‘winners’ in the process of globalisation – are those with high value human capital (i.e. high levels of education and transferrable skills). Meanwhile, the ‘losers’ from globalisation are often citizens with low value human capital or lower levels of education and skills. The relevance of this theory is chiefly that a disproportionate amount of the ‘winners’ who profit from globalisation and European integration are young people.

Furthermore, the effect of individuals’ human capital was particularly pronounced in the recent British referendum, where support for Leave was strongest in areas where a large proportion of the population do not hold any qualifications or occupational skills. Indeed, a report has highlighted how those with low value human capital who are unable to take advantage of the opportunities in the increasingly competitive, post-industrial, skills based economy were far more likely to vote Leave. In sum, the recent British referendum result seems to lend weight to the belief that younger generations, who often hold higher value human capital, are benefitting from the process of European integration to a larger extent than older generations.

The significant British age gap in opinion toward the EU is by no means a recent development, with younger people proving consistently more Europhile than their older compatriots for much of the last 40 years. However, it could be considered – particularly given the influence of individuals’ human capital – that this age division in opinion toward the EU is merely a symptom of a far more severe problem in British society: the growing levels of inequality and feeling of isolation in many Britons who fear they have been left behind by globalisation and European integration.

While it is too late for British policymakers to remedy the growing divisions in British society that contributed to Brexit, other EU member states may look to learn from Britain’s mistakes. Indeed, since the EU arguably faces an existential threat in the coming years, addressing any age gap in opinion and attempting to improve the perceived human capital of European citizens could be key to maintaining public support for European integration in future decades.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Will Thomas recently received an MA in international relations from Swansea University. His dissertation focused on the relationship between age and British opinion toward the EU over the last forty years.

Comment from an ‘old’ (nearly-70) social scientist:

Yes, I see the age (and gender etc) divisions reported here, albeit I personally, like almost everyone I know of my age (I live in that hugely over-privileged city, Liverpool…), am very strongly #RemaIN.

But by what premise is it ‘too late’ in the UK – assuming this Union continues to exist – to do anything about our EU membership?

Please remember (a) that the vote was advisory and braver politicians would be pointing this out forcefully, and (b) by any measure at all only a minority of Britons actually want to leave.

If more young people had actually voted things would be very different, but it’s not ‘too late’ and younger people especially need to say so, loud and clear. It’s their prospects which are at stake.

Social scientists must be careful about how they write about the future; polite scepticism is a valuable tool in our endeavours. ‘IF’ is at present the appropriate term re the #EUref,, not ‘WHEN’.

Is it an age issue or a cohort issue? That is, do people get more Eurosceptic as they get older or is it that people born before [year] are more Eurosceptic than those born after?

There is an uptick in Positive Euro sentiment coming through in 2014+ amongst the older voters. Just noise in the data, or the first sign that those who were postive 15-24 year old in 1984 have kept their pro-EU feeling and are beginning to influence the results for the older age group?

Are you able to analyse the data by cohort to see whether people keep their EU attitudes constant as they get older?