Prime Minster Theresa May gave a speech on 17 January in which she provided further information on the arrangements for Brexit. After Brexit, the UK will no longer be in the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The UK will, once again, take full control of its own laws and the Single Market altogether. The UK will also leave the Customs Union in order to be free to negotiate its own free trade deals. In light of the above, Ruth Lea argues that trade can thrive under WTO rules.

Prime Minster Theresa May gave a speech on 17 January in which she provided further information on the arrangements for Brexit. After Brexit, the UK will no longer be in the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The UK will, once again, take full control of its own laws and the Single Market altogether. The UK will also leave the Customs Union in order to be free to negotiate its own free trade deals. In light of the above, Ruth Lea argues that trade can thrive under WTO rules.

The Government has lost its legal battle to start the Brexit process without first going through Parliament. Specifically, the Supreme Court ruled that the Government cannot trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which the PM has said she will invoke by end-March, without first obtaining Parliament’s approval.

At this stage of the debate it is widely assumed that Parliament, both the Commons and the Lords, will give approval for triggering Article 50. After all, the Commons recently (7 December) passed a Government amendment which stated that its timetable for triggering Article 50 should be respected by Parliament. MPs backed this amendment by 461 votes to 89, a huge margin of 372. Though the vote is non-binding, MPs would need to find fresh objections to the Government’s handling of Brexit if they were to oppose Article 50 enabling legislation with any degree of credibility. And it is almost certain that the Lords will not block the Government’s plans.

This coincides with another important Brexit development, which was the release of the first report of the Commons Exiting the European Union Committee, entitled “The process for exiting the European Union and the Government’s negotiating objectives”. The report called on the Government to publish its Brexit negotiation plan as a White Paper by the middle of February, including clarity about membership of the Single Market and/or Customs Union. The report also called for an outline framework of the UK’s future trading relationship with the EU and transitional arrangements if it is not possible to reach a final agreement by the time the UK leaves the EU. The Committee also wanted the Government to commit to Parliament having a vote on the final agreement. The Government may or may not heed its requests.

More specifically, the Committee suggested that, by the time that the UK exits the EU, it is essential that clarity has been provided for the following, as a bare minimum:

- The institutional and financial consequences of leaving the EU including resolving all budget, pension and other liabilities and the status of EU agencies currently based in the UK.

- Border arrangements between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and a recognition of Northern Ireland’s unique status with regard to the EU and confirmation of the institutional arrangements for north-south cooperation and east-west cooperation underpinning the Good Friday Agreement.

- The status of UK citizens living in the EU and the status of EU citizens living in the UK.

- The UK’s ongoing relationship with EU regulatory bodies and agencies, including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the European Banking Authority (EBA), which are based in London.

- The status of ongoing police and judicial cooperation and the status of UK participation in ongoing Common Foreign and Security Policy missions.

- A clear framework for UK-EU trade.

- Clarity on the location of former EU powers between UK and devolved governments.

Suffice to say, the debate on options for Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU continues to exercise policy-makers. As I have written before, there is much to recommend a bespoke trade deal in order to minimise trade disruption for both UK exports to the EU and EU exports to the UK on Brexit. Specifically, this would, I suggest, prioritise:

- A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU27 (the EU28 minus the UK) in order to retain tariff-free goods trade with the EU. Whilst EU’s trade-weighted average Common External Tariff (CET) is currently low, it is, for example, running at 10% for motor vehicles.

- An agreement on “regulatory equivalence” regimes for financial services, which would act much as “passporting” does now for EEA members.

It is in both the UK’s and the EU27’s economic interests to agree such a deal. Concerning goods, it is arguably more in the EU27’s interests that tariff-free trade continues than in the UK’s as it runs such an enormous visible trade surplus with the UK. According to the latest figures the UK’s visible trade deficit with the EU was £89.0bn in 2015. The deficit with Germany alone was £31.1bn. Deficits were also sizeable with the Netherlands (£14.8bn), Belgium-Luxembourg (£9.5bn), Italy (£7.5bn), France (6.4bn), and Spain (£5.1bn).

The EU wants easy access to the City after Brexit

When it comes to the financial services sector the situation is somewhat different as the UK runs a surplus with the EU. But, as the Governor of the Bank of England said recently to the Treasury Select Committee (11 January), failure to secure a deal with Brussels on the City would arguably pose a bigger financial risk to the EU than to the UK on Brexit. He told the MPs “there are greater financial stability risks on the continent in the short term, for the transition, than there are for the UK” if there was no Brexit deal. Incidentally, he also said that Brexit no longer posed the biggest risk to domestic financial stability, as concerns were rising about the growth of consumer credit.

And a recent Guardian report suggested that Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator for Brexit, has shown the first signs of backing away from his hard-line, no-compromise approach after admitting he wanted a deal with Britain that will guarantee the EU27 member states continued easy access to the City after Brexit. According to the report, Barnier, in some unpublished minutes that hinted at unease about the costs of Brexit on continental Europe, had expressed the wish for a “special” relationship with the City of London,. “Some very specific work has to be done in this area,” he said, according to the minutes (apparently). “There will be a special/specific relationship. There will need to be work outside of the negotiation box …in order to avoid financial instability.”

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) option

The prospects for a bespoke deal are, therefore, reasonably positive. But, if there is no bespoke agreement, then the default position would be that the UK, a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), would trade under WTO rules. The UK would, for example, face the EU Common External Tariff as EU exporters would face the tariffs adopted by the UK. There is, however, convincing evidence that trade can thrive under this regime, given favourable commercial circumstances. Preferential trade deals may oil the wheels of international commerce, but their importance should be kept in perspective. If the commercial circumstances are adverse, trade will not thrive, irrespective of special trade agreements.

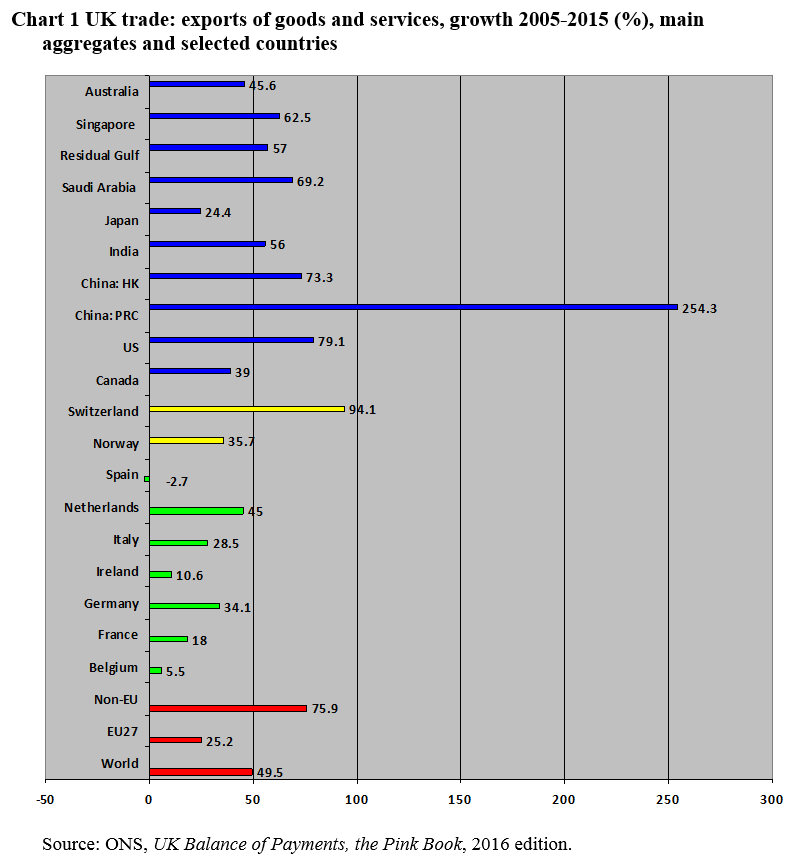

Moreover, over the last decade not only has UK exports to the non-EU grown quicker than with the EU, but UK exports to non-EU countries that have no preferential trade deals with the EU has been buoyant. Chart 1 includes the growth rates in exports in goods and services for 2005-2015 (inclusive) for Britain’s key trading partners. The main conclusions are:

- The red bars show the key aggregates. Total exports over this period grew by nearly 50%, whilst exports to the EU and the non-EU expanded by 25% and 75% respectively.

- The green bars show trade with our seven largest EU partners. Whilst exports grew 45% with the Netherlands, it actually slipped by nearly 3% with Spain. Additionally, exports to Sweden grew by over 30%, exports to Poland grew by 100% and exports to Denmark were 37.5% higher.

- The yellow bars show the two non-EU countries that have preferential agreements with the EU, which do the most trade with the UK. They are Norway and, especially, Switzerland. Switzerland is by far the most important trading partner in this category. As we have discussed previously the EU’s suite of trade agreements does not fit especially well with the UK’s trading patterns – EFTA’s are better.21 Additionally, exports to South Korea grew by over 130%, exports to Turkey grew by nearly 80% and exports to South Africa were nearly 25% higher.

- The blue bars show trade with non-EU countries that do not have preferential agreements with the EU. Some growth rates are spectacular in this category, as can be seen from chart 1. Granted China (PRC) is in a class of its own, with exports in 2015 3½ times as large as in 2005, and it can be expected that such a blistering rate of growth will not continue as the Chinese economy matures. But strong growth was also recorded for the US, our single biggest export market, Hong Kong, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Residual Gulf States (Gulf States excluding Saudi Arabia), India, Australia and Canada. Exports to Japan grew by nearly 25%. In addition, exports to Russia were up nearly 90% . Trade with non-EU countries, under WTO rules and in the absence of preferential trade agreements, can clearly thrive. Indeed, commercial factors and growing markets are arguably of far greater significance than trade agreements.

If the UK trades with the EU under WTO rules then UK exporters will, as noted already, face the EU’s Common External Tariff. But, as William Norton argues in a recent paper for Civitas, such costs should be quite manageable and could be mitigated. His basic conclusions were:

- In the absence of any agreement with the EU, imports from the EU will raise £12.9bn for the Treasury in duties, whilst UK exporters will face £5.2bn in total in tariffs on their exports to the EU.

- WTO rules on subsidies provide sufficient flexibility for the Government to implement “horizontal” programmes to mitigate the impact of tariffs. Such programmes are economy-wide measures which are not specific to any identifiable industry, and are not tied in principle or in practice to compensating for the exact cost of tariffs on exports.

An earlier, extended and fully referenced, version of this post can be found here.

The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics. Image by World Trade Organization: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0.

Ruth Lea CBE is Economic Adviser at the Arbuthnot Banking Group.

There’s lots of problems with this post which could do with a more serious rebuttal if I had the time. Here’s some fairly random comments:

It is highly misleading to mention The Guardian report on Michel Barnier without mentioning that his official spokesman went on record to say it was wrong. Equally there has been a united front from every EU leader on their hardline position.

When talking about our trade with South Africa it would have been worth mentioning that it is under an EU deal. It is misleading the way it is worded as it implies that is under WTO rules.

It is true that more exports go the US than any individual EU country but it is misleading to say the US is the biggest destination for UK exports without mentioning that more exports go to the EU.

Finally, to suggest that government subsidies should be applied to industries that export to the EU is completely mad. The point of Brexit is to disengage the British economy from Europe and instead to focus on Asia and America. Public investment should be spent on the new opportunities not propping up legacy industries that rely on the EU.

But I’ve said South Africa has a preferential trade deal. The chart makes it clear more exports go to the EU than the USA. My fully referenced article (referenced) includes the comment by the EU’s official spokesman on Barnier – do read. And help for business strikes me as entirely sensible. So much for your rebuttal. Why don’t you read articles before you “comment”

PS the point of Brexit is not to “disengage” from Europe & focus on Asia & America. It is to be a “Global Britain” (& that includes the EU).

I’m glad the fully referenced article was more balanced, I was however was commenting on the piece above.

Ruth Lea has long been in a minute group of economists that have an idealogical dislike of the EU, yet attempt to portray themselves as empirical sceptics. The public may like an underdog, but using out of date analysis and modelling techniques along with poor data means that in academia we have a tendency to dismiss you, with good reason.

“….in academia….”

Yes, quite.

The increase in trade with non-EU countries is attributable to the growth of the BRIIC nations and also free trade deals struck by the EU with non EU countries such as S Korea that we will lose post brexit.

The EU represents 20% of world GDP

We will not have anything like that kind of fire power when we renegotiate.

Re financial services equivalence does not work in the same way as passporting

See open europes paper on this.

Financial services is one third of Uk service exports to the EU what about the other two thirds?

Ruth has said elsewhere that single market for services is crap!!!!

Why is it our biggest service export market?

WTO does little for services

Perhaps, those who work for financial services should do something else…

It seems misleading to use a chart of trade “growing” to illustrate trade “thriving”. Aus might have grown by 45% but it’s still a very low percentage (1% of UK trade).

Key question about WTO terms is how much trade with our biggest market – the EU (45%) will decline.This is not explored.

What’s more , the trade growth with non-EU countries shown is of course whilst the UK is trading as an EU member. As it’s thriving, the argument for freeing us from the EUs trade regime seems seriously weakened !

And….no mention of the UK having to become a full members of the WTO (untied from the EU) with revised schedules, TRQs, MRAs etc.

Just read this prior to your article, it seems pretty well argued on the issues with a WTO option:

http://www.standard.co.uk/business/anthony-hilton-disaster-lurks-in-may-s-empty-bluff-on-trade-a3480301.html

South Africa has a preferential trade deal.

It is the Irish situation that leaves only two available options: A free trade agreement, in which case there would not need to be a trade border, or WTO Rules, in which case the boundary could only be between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland.

The third possibility, of a border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the U.K ,is unacceptable to the DUP without whose votes the UK government has no majority. Probably also not a legal possibility.

Ruth Lea has long been in a minute group of economists that have an idealogical dislike of the EU, yet attempt to portray themselves as empirical sceptics. The public may like an underdog, but using out of date analysis and modelling techniques along with poor data means that in academia we have a tendency to dismiss you, with good reason.

South Africa has a preferential trade deal.

South Africa has a preferential trade deal.

totally agree with this article

South Africa has a preferential trade deal.

It seems misleading to use a chart of trade “growing” to illustrate trade “thriving”. Aus might have grown by 45% but it’s still a very low percentage (1% of UK trade).

It seems misleading to use a chart of trade “growing” to illustrate trade “thriving”. Aus might have grown by 45% but it’s still a very low percentage (1% of UK trade).