Once the UK has left the Single Market – and assuming it does not join EFTA or negotiate a bespoke deal with the EU – it will have to revert to World Trade Organisation membership. In this extract from its latest report, the LSE Growth Commission explains that in the absence of bilateral deals this will mean determining a universal set of tariff rates. Keeping nontariff barriers low will also be important. Given the UK’s dependence on trade with the EU and US, these deals must take priority over other countries.

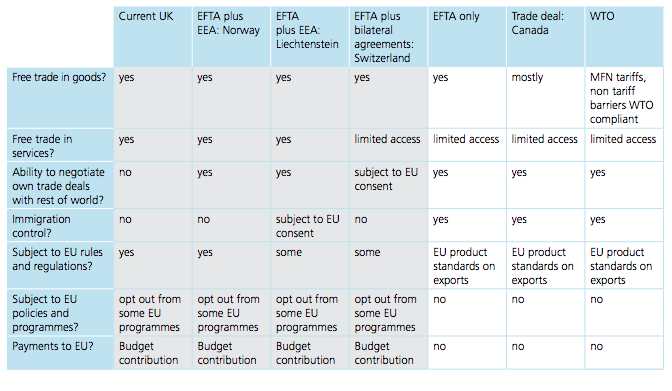

The political and legal landscape surrounding Brexit is evolving at a fast pace and there is still a high degree of uncertainty over its likely form. A number of options appear to have been largely ruled out (these are shaded in grey in Table 1 which shows the key attributes of different Brexit models). In its recent White Paper on the UK’s exit from the EU, Government has stated that border control will be a priority and that therefore, the UK cannot remain in the EU’s Single Market. (Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland are not EU members, but have access to the Single Market via membership of the European Economic Area (EEA)). Moreover, staying in the Customs Union appears unlikely as this limits the UK’s capacity to negotiate its own trade deals which is another of the government’s key objectives.

This implies that the UK will need to find a bespoke trade agreement with the EU. One option – which may be difficult politically – is re-joining EFTA, which would provide tariff-free trade in goods. The other option is to negotiate a bespoke deal of the type recently agreed with Canada. Neither would guarantee free trade in services, and would still result in significant non-tariff barriers in goods markets such as complying with rules of origin. The UK must therefore aim for a better deal than either of these options, in particular with respect to the services sectors where the UK has comparative advantage, acknowledging that there is likely to be some cost or concession to achieve it.

In order to revert to World Trade Organisation (WTO) membership, the UK would first have to become an independent member of WTO. If this did happen and became the default, then under WTO rules, each member must grant the same ‘most favoured nation’ (MFN) market access, including charging the same tariffs, to all other WTO members. The UK would then have the same trading relationship with the EU as any other country. In the absence of any bilateral trade agreements with the EU (or any other countries) the UK would have to determine a universal set of tariff rates to apply with all trading partners. If tariffs are too high, imports will be more expensive, harming UK consumers and businesses which use significant imported inputs. While lowering tariffs would make imports cheaper, there is no guarantee that this would be reciprocated, and the UK will lose bargaining power: once duty-free access to the UK market has been offered, other countries will have no incentive to give the UK preferential access to their own markets.

It is crucial that the system replacing EU membership is able to maintain low tariffs with the EU. But equally crucial is the need to constrain nontariff barriers to trade which add substantially to trade costs. Adherence to EU rules and regulations have been an essential component of reduced non-tariff barriers. So even outside the EU, it is likely that harmonised rules will be required in any deal that preserves high levels of market access.

There are some areas that could be particularly problematic. For firms participating in global value chains, with high shares of imported inputs, the bureaucratic cost of complying with EU rules of origin are high and may reduce the UK’s attractiveness as a location for production processes. Moreover, the financial costs associated with expediting tax (VAT) and customs clearance are especially important for small exporters. As previously discussed, small and medium enterprises do not typically export and those that do currently focus on the EU market. (9% of SMEs export and a further 15% are in the supply chains of other businesses that export. Most of this relates to the EU.) It has been argued that leaving the EU provides the UK with more freedom in designing domestic policies and regulatory frameworks aimed at increasing firms’ profitability, which may compensate for the rise in administrative costs implied by Brexit. The UK would have the freedom to redesign all areas currently under the authority of the EU, including competition policy, international trade regulations, and areas that rely on EU funding like regional development and research. However, any new subsidies or regulations that do not comply with EU or WTO normative standards may result in the imposition of further market restrictions from global trading partners. More generally, a lack of coordination in competition policies with the EU will provide more freedom for domestic policy design, but will leave UK firms vulnerable to antidumping measures and less able to export. Moreover, it is worth noting that any country that exports goods to the EU has to comply with EU product standards.

Table 1: Brexit options

New relationships with the rest of the world

By exiting the EU, the UK will be allowed control over trade deals with non-EU countries. While the UK will now be able to seek trade agreements tailored to UK interests, it will have reduced bargaining power with large trade partners like the US and China once it is outside the largest trading bloc in the world. There is a risk, therefore, that the UK will have less power to negotiate deals that are in its longterm interest.

Exploratory talks have already taken place with a number of countries, most recently the US, but also New Zealand, Australia and Gulf nations. Our analysis of UK trade shows that while all such deals are positive developments, the UK must prioritise deals with the US and EU.

Currently the UK and the US trade under WTO terms. Tariffs are already relatively low, and the largest gains would be from reducing non-tariff barriers, for example through regulatory harmonisation. This may now be more difficult. Under the previous US government, a wide-ranging deal was being negotiated with the EU (the TTIP) , but the general consensus so far is that President Trump will be more protectionist than his predecessor.

In the coming years there are opportunities to increase exports to China and India. Both have rapidly growing middle classes with a preferences for goods and services where the UK has comparative advantage.

It is important to note that deepening international integration with non-EU countries – in particular emerging markets – implies different challenges than those faced in current partnership with the EU. European economies are relatively similar to the UK in terms of education, labour costs, and environment regulations. As a result, much of the gains from trade within the EU are based on economies of scale and access to broader varieties of goods and inputs. The gains from trade with labour-abundant economies such as China or India are based on complementary patterns of factor abundance.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog. It is an extract from the LSE Growth Commission’s UK Growth: A New Chapter report, in partnership with the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. Find out more about the Growth Commission.

Two legal clarifications. First, the UK is a WTO Member, with existing scheduled obligations, as Liam Fox stated to Parliament in December. Its bound rates are already set, give or take some need for determining – as a legal matter – the UK’s share of TRQs and AMS. Second, less important, joining EFTA does not give the UK any access to the EU market. Perhaps you mean the EEA.

@lorand bartels: neither of your statements is correct. While the UK is a distinct member of the WTO, there are no schedules attached to that membership. The UKs schedules are part of those held by the EU; that is why Liam Fox is attempting to copy the current EU schedules (worth noting this wont succeed as they will be disputed by half the WTO members as soon as they are submitted). Secondly the author does not mean the EEA; EFTA has access to the single market in its own right

Well, I think I am right. On point 1 see this: http://www.ictsd.org/opinion/understanding-the-uk and note Fox’s statement that the new draft schedules will reflect as far as possible the UK’s ‘current obligations’. The ‘as far as possible’ is for the TRQs and AMS. Admittedly, this is only an argument. But it is the same line the government is taking, so at this point you’d need to explain the contrary (and please do: I’m open to criticism). On point 2, I think you’ve just got this factually wrong. EFTA is Switzerland, Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. EFTA states have EU access via bilaterals (Switzerland) and the EEA (the other three).

All EFTA members have free trade in industrial goods with the EU providing they accede to the 1972 EFTA-EEC FTA. This is still the cornerstone of Swiss-EU trading relations. Since a provision of that treaty bans the erection of new tariff barriers, were the UK to accede to this treaty it would have tariff-free trade on all goods.

But that’s not true either. The 1972 Agreement is this one: Agreement between the European Economic Community and the Swiss Confederation (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:21972A0722(03)&rid=1). Or have I got this wrong?

That agreement has been signed by numerous EFTA members; all but Switzerland have since either joined the EU or joined the EEA, and these arrangements then replaced this FTA. Currently it just applies to Switzerland.

There would be no non-punitive reason to deny U.K. Accession, especially as the original raison d’etre of the FTA was to prevent disrupting trading networks as the U.K. Moved from one Western European trading bloc to the other one.

The EFTA countries had bilaterals with the EEC. Here is the Norwegian one: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1488444632251&uri=CELEX:21973A0514(01)

No, all EFTA members but Norway signed up to the Swiss deal. Norway is a special case as it was supposed to join the EEC at the same time as the UK but the electorate rejected it in a referendum in 1972. For that reason it didn’t join the negotiations for the 1972 EFTA-EEC FTA.

So here is the separate Iceland-EEC agreement: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1488498294833&uri=CELEX:21972A0722(05). So with Liechtenstein joining CH as a special case, we have three separate EEC agreements. Pretty much as I said, no? Or am I wrong? And if so, perhaps you can do some digging for references.

Looks functionally the same to me. EFTA agreements often have variance between different members – an annex may only apply to one member, for example. This FTA was negotiated between the EEC and EFTA members at the same time and for the same purpose.

Anyway, I don’t know what your point is, unless you seriously believe that after 40-odd years of precedent applying free trade in industrial goods to EFTA members the EU would deny the same to another EFTA member.

Well, being accurate makes a difference. To a lawyer at least. For example, there is nothing doe the UK to accede to – other than the Swiss bilateral, which is obviously impossible. So your argument falls down. Now it’s just politics. Second, you could have the basic decency to admit you were wrong. On the upside, my knowledge of the EEA’s prehistory has been improved.

Basic decency??? I’d have thought a lawyer would have sufficient grasp of English to know that the only appropriate response to such language involves the very longest of fingers.

Lawyers: everyone’s favourite profession.

If you do insist on accuracy, the EEA was probably not even dreamed of in 1972. The word you’re looking for is not ‘prehistory’ but ‘precursors’.

Have fun soliciting!

OK, I guess our conversation is at an end. But seriously, I had said something that was entirely correct. You picked me up on this, but wrongly. In anyone’s book – not just those of the maligned profession I belong to – that would deserve an acknowledgement. Oh, and ‘prehistory’ is entirely the correct term. Lorand

Oh my days! Lorand, you’re a Cambridge academic and you’re *this* intellectually needy? Amazing, I had genuinely assumed you were a law undergrad.

Ok, so the EEC-EFTA free trade agreements of 1972 were bilaterals; however they were almost all signed on the same day, 22 July 1972. This strikes me as no coincidence. Moreover, the objective of the FTA was to create a free trade zone in industrial goods, as I said. Furthermore, the motivation for the FTA was just as I said, namely:

“The Community had decided at the

Hague Summit in December 1969 that negotiations

should also take place with the EFTA countries,

on the understanding that:

• the enlargement of the Communities should

not involve the re-erection of tariff barriers in

Europe;

• the Agreements with the non-candidate countries

should, if possible, enter into force at the

same time as the candidate countries took up

membership of the Communities.”

http://www.efta.int/sites/default/files/publications/efta-commemorative-publications/40th-anniversary.pdf p. 28

These motivations would also apply to the UK moving between the EU and EFTA.

I therefore conclude that in spirit I’m correct; in some more inconsequential hair-splitting concerns you may have a point.

At least I now know that calling something ‘prehistoric’ does not imply a major rupture. I content myself with looking over your previous posts in which you have expressed your views, and loudly exclaiming ‘well this is all prehistoric stuff. Antediluvian!’. And then I shall leave this matter behind in my own prehistory.

I wish you well, and I hope and pray that you are never hit by a giant asteroid as you graze.

You are a really quite impolite, aren’t you? I’m not intellectually needy. Or an undergrad. I prize accuracy, like any lawyer. And I haven’t even got started on the political economy of this. Nor will I with someone so awful to talk to.

Lorand

That should be “you are really quite impolite”.

Accuracy, Lorand. It’s the prize.

Oh, and to your point about the UK not succeeding in having its schedules certified: that does not matter. Until that happens, the old EU/MS schedules apply. The alternative, which is not always thought through, is that the UK has no scheduled obligations, which is not a position anyone would want to take. Certainly one can expect requests for negotiations under Art XXVIII GATT and XXI GATS, based on an alleged ‘modification’ of the UK’s obligations (which by the way reinforces the previous point: there have to be schedules that are claimed to be modified). But those provisions are limited to the harm that is caused by the alleged modification. In the UK’s case, that is going to be fairly minor, in overall terms, if at all, and, as said, limited to TRQs and AMS calculations. Of these, it is only TRQs that are of any real interest, but even here the compensable harm, if there is any, is the difference between the UK’s interpretation and the actual interpretation (as determined ultimately, if necessary, in dispute settlement). That is not going to be particularly significant.

Looking forward to your reply.

“Currently the UK and the US trade under WTO terms.”

Just to clarify this point: there are more than 20 trade agreements between the EU and the US. These agreements are not a full Free Trade Agreement (FTA) but they do help massively and most EU and US trade is covered by these agreements to some extent.

So it is very important to understand that the UK’s trade with the US will be disrupted if the UK is forced to fall back on pure WTO terms.

Indeed this also applies to many other countries (such as China) where although the EU does not have an FTA it still has extensive agreements.

Only if we don’t agree with the US, China etc to continue as we are currently, which may happen or may not.

In fact we could drop some of the ridiculous EU tariffs on things like training shoes and Durham wheat which we don’t produce.

Although it would be anathema to the EU Commissariat, there is room for a worldwide open market,i.e., a free trade arrangement whereby individual nation-states trade freely in the world market.Sofar, Free Trade Agreements have been anything but.

this piece and more, the comments below suggest that these are matters best left to experts, and certainly not to the general public.

“By exiting the EU, the UK will be allowed control over trade deals with non-EU countries. While the UK will now be able to seek trade agreements tailored to UK interests, it will have reduced bargaining power with large trade partners like the US and China once it is outside the largest trading bloc in the world”

Not true.

Currently we have zero bargaining power because, while we have a say, we are outnumbered in the EU. The feet dragging and protectionist stance of other EU countries mean we’ve achieved very few and very limited free trade deals.

Outside the EU we can do deals with, say the US, which suit both countries and no-one else. That means the deals are likely to cover a larger range of goods and services. As for “large trade partners” we’re the 5th or 6th largest market in the world on our own, every country in the world wants access to the UK market

I knew about EFTA-EEA and EFTA- Swiss bi-lateral model as options before.

But this article offers a new one to me e.g. EFTA membership alone, which the table claims, would give us free trade in goods with the EU.

So why don’t we just do that then? At least as an interim?

We were in EFTA before we joined the EU and I read that the EFTA secretariat said it would welcome a UK application now.

Because that is not what would happen. EFTA membership would give access (not in services) to Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

Doesn’t the EFTA agreement include free movement of workers?

Also it’s implied that adherence to EU product standards is sufficient to meet EU regulations on exports. This is necessary but not sufficient. EU regulations define has many processes that apply to third countries and must be adhered to – e.g. animals and animal based products must enter EU via Border Inspection Post, to scratch the surface.

I have seen many articles like this which are very “big picture” – but the real impact can’t be understood until you look sector by sector at what the WTO implications really are for an industry – the devil is in the detail.