Some Leavers claim the referendum result was not primarily about immigration, but anxiety about Britain’s perceived loss of sovereignty to the EU. In their new book, Harold D. Clarke, Matthew Goodwin (left) and Paul Whiteley draw on data about more than 150,000 voters to analyse the factors and concerns that led people to vote Leave. The mix of calculations, emotions and cues were complex, but immigration – and the personal appeal of Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson to different groups of voters – were key.

Some Leavers claim the referendum result was not primarily about immigration, but anxiety about Britain’s perceived loss of sovereignty to the EU. In their new book, Harold D. Clarke, Matthew Goodwin (left) and Paul Whiteley draw on data about more than 150,000 voters to analyse the factors and concerns that led people to vote Leave. The mix of calculations, emotions and cues were complex, but immigration – and the personal appeal of Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson to different groups of voters – were key.

Britain is approaching the one-year anniversary of the vote for Brexit. Yet the question of why a majority of people voted to leave the European Union (EU) remains contested. Since nearly 52 per cent of the country opted for Brexit, some have argued that the vote was motivated mainly by concerns over national sovereignty, while others have pointed to an economically ‘left behind’ group of voters, or to intense concerns over immigration. In a new book published this month we contribute to this debate.

The book, Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the EU, draws on twelve years’ worth of data from representative national surveys, conducted each month from April 2004 until June 2016. They probed the backgrounds and concerns of more than 150,000 voters and in June 2016 included a panel design, whereby voters were contacted a few days before the vote and right after. These data provide unprecedented insight into the Brexit vote.

Our starting point is an established literature on what shapes public attitudes toward the EU, which stresses the importance of calculations about perceived costs and benefits of being in the EU, the role of risk, emotion, leaders, and public concerns over domestic and ‘identity-related’ issues, such immigration. In short, our argument is that Brexit was not driven by ‘one factor’. The vote to leave the EU reflected what we refer to as a complex and cross-cutting mix of calculations, emotions and cues. Within this, immigration was key.

By tracking public attitudes toward EU membership over the long-term, we show how the ‘fundamentals’ of the Brexit vote did not suddenly appear in 2016 but were ‘baked in’ long ago. By examining what shaped volatility in these attitudes since 2004, we show how people’s views of the EU were strongly shaped by their assessments of how the main parties had performed on key ‘valence’ issues, but mainly immigration and the economy. If people felt anxious over migration, ‘left behind’ economically, and worried about the control of Brussels, they were significantly more likely to oppose EU membership long before David Cameron even called the referendum.

Then, as Britain trundled toward the 2016 referendum people began to assess the costs and benefits of EU membership. Crucially, a plurality accepted that Brexit would harm the economy, and probably their own finances as well. But most voters also felt that remaining in the EU would increase the risk of terrorism, harm Britain’s cultural life and erode sovereignty, while leaving the EU would mean less immigration. Identity concerns were already trumping economic self-interest. It is likely that Angela Merkel’s decision only a few months before the vote to allow large numbers of refugees into the EU sharpened this concern and entrenched a view that politicians (and the EU) were not in control of an issue that a large section of the electorate cared deeply about. For reasons that we set out in the book, Cameron’s renegotiation with the EU failed to quell these concerns.

It is worth underlining the point that people accepted Brexit was a risk, a belief Cameron and Remainers sought to amplify through their elite-focused campaign. They recognised that many voters were risk averse and carpet-bombed them with dire warnings and prophecies. When asked ahead of the vote to indicate how risky they thought leaving would be (on a scale of 0-10 where ‘0’ is ‘no risk’ and ‘10’ is ‘very risky’), 54 percent of voters assigned scores of six of greater. Playing on this notion of risk was not necessarily a ‘bad’ strategy –believing Brexit was risky was the strongest predictor of whether or not somebody voted to Remain.

But on its own the risk-based strategy was not enough, especially when set alongside the powerful and emotionally resonant case over immigration. Our findings reveal how perceptions of risk were not distributed evenly, which meant Remain were unable to cut through to key groups who would go on to vote for Brexit in large numbers. Our statistical analysis reveals people who felt negatively toward immigration, worried about a loss of control to Brussels, and had been left behind economically were much more likely to minimise the risk of Brexit. These voters felt they had nothing to lose, or were determined to force their identity concerns onto the agenda regardless.

By examining emotions, too, our book points to another problem for Remainers, who spent too much time trying to amplify the problems of Brexit at the expense of making the positive case for EU membership. After worries about the risks of Brexit, the second strongest predictor of the Remain vote were positive feelings about the EU –a driver that was not maximised by Remainers. Might things have been different if Cameron, George Osborne and Barack Obama had consistently made the positive case for Europe?

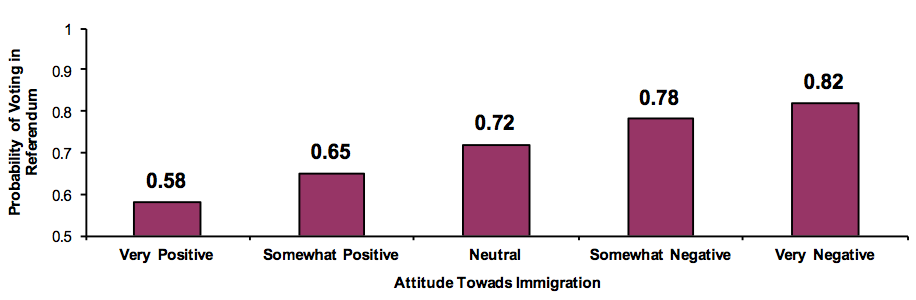

On June 23 2016 all of these dynamics came together to deliver the vote for Brexit—a choice that reflected a complex mix of calculations, emotions and cues. Immigration was key to the vote for Brexit and ran through this decision. Not only were those who felt negatively about immigration more likely to minimise the risks of Brexit but they were also significantly more likely to turnout, and then vote for Brexit in the polling booth. Immigration exerted powerful direct and indirect effects on the vote. The idea that this issue, which gave Leavers an emotional appeal that Remain’s economic pessimism could not match, was not central is misleading. Indeed, weeks before the balloting we argued that Leavers were more likely to show up at the polls because of this ‘enthusiasm gap’ –and they did.

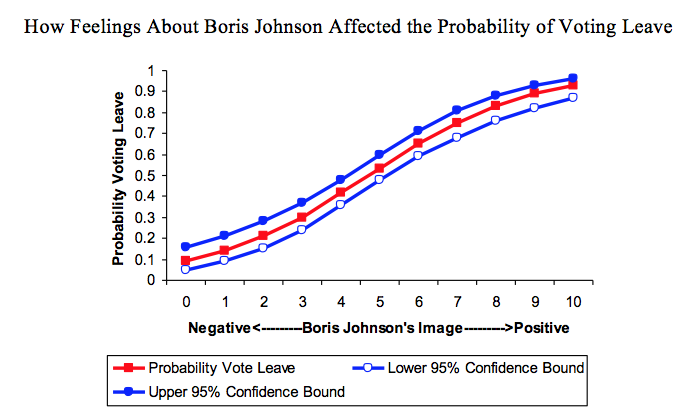

Though Leavers were divided on how to deal with immigration, our findings also point to the important role of ‘cues’ from leaders, specifically Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. Johnson had a particularly important effect –if you liked Boris then even after controlling for a host of other factors you were significantly more likely to vote for Brexit. Farage was less popular among the professional middle-classes but he was more popular among blue-collar workers and left behind voters, underlining how these rival messengers were able to reach into different groups of voters. When, from June 1 2016, the rival Leave camps all put the pedal down on immigration they were firmly in tune with the core driver of their vote. Neither Cameron nor Corbyn were nearly as effective for Remain. Leader cues were much stronger on the Leave side.

In conclusion, the story of why Britain voted for Brexit is straightforward. Propagated by an unlikely pair of messengers, Leave’s ‘Take Back Control’ message harnessed the emotive power of immigration, amplifying public concerns over identity and a feeling of being left behind that had been baked in long before the vote was called. These immigration fears, hitherto confined to the politically incorrect margins, not abstract concerns about a ‘democratic deficit’ or rescuing UK sovereignty from Brussels bureaucrats, do much to explain why Britain voted for Brexit.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Harold D. Clarke, Matthew Goodwin and Paul Whiteley are the authors of Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Farage deserves a knighthood for his part in Brexit.

As for the “remain camp” failing to talk up the positives of the EU, that would be difficult given how few they are.

I was a Vote Leave member who delivered thousands of leaflets and knocked on doors to get the vote out. I noticed that among my fellow door knockers immigration had little resonance; indeed several were immigrants themselves and all were strongly motivated by sovereignty and the democratic deficit. But the motivation of those answering our door knocks was I would estimate 60% immigration and 40% other issues, with the cost of EU membership featuring strongly as well as sovereignty. Anyway; we won (thank god) and history will show we were right and project fear doom-mongerers wrong.

But why don’t you think of the children and teenagers who need a better education?

“Since nearly 52 per cent of the country opted for Brexit…”

They didn’t. About 37% of the electorate voted for Brexit, far too few normally to make a significant constitutional change in an advanced democracy.

Do you also hold that view when a Government is voted in on a much lower percentage of the votes cast?

I think we should have a written constitution and that major constitutional change should require some kind of meaningful threshold to be met. There was debate in the House of Commons over a threshold, for which there is precedent in English politics (early devolution refernda) but David Lidington specifically ruled this out on the grounds that the Referendum was “merely advisory”.

I note that you don’t seem to have understood the point of my post, despite the fact that its meaning is perfectly plain, and that you are a supporter of Nigel Farage. Please try not to stoke my prejudices.

Has the EU ever changed its direction of travel, towards ever greater integration? Have any of the EUrocrats ever been voted out of office because the European electorate wanted a change of policies? Has the EUrocracy ever been held accountable, or thrown out of office, for its policy disasters, such as the creation of the Euro with its disastrous consequences for several national economies? What mechanism does the EU have for throwing out the entire EU Commission and replacing it with officials who are more in tune with the wishes of the EU electorate? When did the EU consult the EU electorate about whether they wanted to see the creation of a European superstate, with citizenship, a president, a foreign minister, and an army? Indeed, when did they ever ask the EU electorate whether or not they wished to become “citizens” of the EU?

In short, the whole modus operandi of the EU is repugnant to the British notion of democracy.

“Indeed, when did they ever ask the EU electorate whether or not they wished to become “citizens” of the EU? In short, the whole modus operandi of the EU is repugnant to the British notion of democracy.”

Remind me of the election in which I was asked whether I wanted to be a UK citizen. I seem to have missed that one. Along with the election in which I got to eject the entire civil service. Or the House of Lords. Or the monarch.

Anti-EU rhetoric on the “democratic deficit” seems to me to be generally hypocritical. If the EU were to be run as a democratic state, then it would become precisely the “superstate” that so many of its opponents profess to abhor. Since it is a compromise arrangement, with political supremacy still lying largely with nation-states, it can be criticized from all sides by comparison with some ideal democratic arrangement, which usually, on close examination, turns out not to exist.

There is a parallel here with the economic arguments. There is much to criticize about the UK’s economic participation in the EU, but the criticisms pale into insignificant by comparison with the alternative, as the Brexiters are apparently only now beginning to learn.

Chris, thank you for replying to my comment. As you would expect, I do not agree with your line.

The British people can remove the British government if they fall out of touch with the wishes of the electorate. Every five years the British electorate are asked, essentially, if they are happy with the direction the government is taking the country. If not, the government gets kicked out and a government with a different agenda takes office. The incoming government is perfectly capable of performing a complete U-turn on important aspects of previous government policy.

The EU, by contrast, has had a single policy direction throughout its existence, namely ever-closer union. This policy objective has been pursued at times by stealth, at other times by bold initiatives such as monetary union. The policy itself, of ever-closer union, remains both unchallenged and unchallengeable. All that ever changes is the speed with which the policy is implemented.

Are you happy with the policy of ever-closer union? Do you support the creation of a single European superstate? Do you, for example, support monetary union – and with it the creation of the Euro – as being a vital step towards deeper political union? Do you support the creation of EU “citizenship” as being another important step in this process? If so, then that’s perfectly fine, that’s your prerogative. The EU is your natural home. But a majority of the British people do not agree with you; they do not like the destination the EU train is heading towards, and, given the opportunity to vote on the matter, they voted to get off the train.

The Remain campaign tried to portray a “Yes” vote as voting for the status quo. This was disingenuous of them; it would have been more honest if they had stated clearly that voting “Yes” meant voting to continue the process of closer integration. But fortunately a majority of the British people understood this anyway, and rejected it.

Your comment, “Since it is a compromise arrangement, with political supremacy still lying largely with nation-states …”, goes right to the heart of the matter. The EU’s policy is to gradually erode the political supremacy of the nation states. Little by little, it is succeeding. It is a process achieved by the accumulation of many small steps. For example, over the coming years the individual nation states – particularly those within the Eurozone – will gradually see greater and greater EU control over their ability to independently produce national budgets.

I do not expect you to agree with me. But I would be pleased to hear from you your reasons for supporting the goal of ever-closer union.

“The EU… has had a single policy direction throughout its existence, namely ever-closer union. This policy objective has been pursued at times by stealth, at other times by bold initiatives such as monetary union. The policy itself, of ever-closer union, remains both unchallenged and unchallengeable. All that ever changes is the speed with which the policy is implemented”.

With great respect, I don’t think this is really the case. I think it’s very clear that in the months before the UK advisory referendum there was widespread acceptance across Europe that ever-closer union was off the table – not least because the German population clearly did not want “financial solidarity” with the countries of southern Europe. But also because the UK and some of its allies in northern and eastern Europe would mount vigorous opposition against it.

The situation has changed now, of course. Brexit is one factor, the rather lukewarm support for NATO from the erratic Trump is another. This latter factor has meant that EU defence cooperation will definitely have to speed up: anything else would be irresponsible.

“But a majority of the British people do not agree with you; they do not like the destination the EU train is heading towards, and, given the opportunity to vote on the matter, they voted to get off the train.”

One day someone suggests (often on the basis of copious research) that the EU referendum was all about reducing immigration, another day someone else suggests it was about sovereignty. I have Indian neighbours in the West Midlands who thought that if they voted for the UK to leave the EU, it would be easier to bring family members to the UK. I’ve no idea why people voted for the Leave option in the advisory referendum, but I have family members in the north of England who were just trying to send a signal to Westminster that they weren’t happy with the government. I suspect plenty of others were only trying to “blow the bloody doors off”. Presumably, many people must have voted for Daniel Hannan’s proposition that we could leave the EU but remain in the single market and the customs union.

I’ve generally found that the idea of an EU train bound toward a supra-national destination was of interest only to a very small core of nationalists who, when I’ve met them, have turned out to be UKIP members or voters. Oddly enough, many of them also turn out to be nostalgic for another supranational institution, though one that mainly spoke English.

That’s their prerogative. But it seems a very blinkered view of how the world now works (or can work). And Brexit will not be kind to them. The Commonwealth as an economic institution is long gone. A free-trade deal with the US would involve investor rights agreements, meaning that multinational corporations rather than the UK parliament would be sovereign, and also an agricultural deal that would kill off most of the environmental protection we could negotiate as part of a larger entity. A deal with China would probably threaten such lower-level manufacturing industry as we still have. A free trade deal with India would mean agreeing to higher levels of “commonwealth” immigration than we currently experience. And much of the country’s current wealth will gradually (or, in the worst scenario, rapidly) decline because of the obstacles that will arise to trade in services (our main export).

“Are you happy with the policy of ever-closer union?”

Yes.

“Do you support the creation of a single European superstate?”

Yes, bring it on.

“Do you, for example, support monetary union – and with it the creation of the Euro – as being a vital step towards deeper political union?”

I support monetary union, but it doesn’t work well as a way to create political union. Greater political union is needed before monetary union can work properly.

“Do you support the creation of EU “citizenship” as being another important step in this process?”

Yes. I’d opt to become an EU citizen today if I could, in just the same way that I am currently a UK citizen, not a Greater London one.

“But a majority of the British people do not agree with you; they do not like the destination the EU train is heading towards, and, given the opportunity to vote on the matter, they voted to get off the train.”

They voted to get off the train because they were lied to about how easy that would be, and how much better they would be once off, and because, for the majority, they were “racists”. The destination didn’t matter – it was their fellow passengers they couldn’t stand.