The Great Repeal Bill is intended to convert all existing EU law into UK law. The aim is to provide legal certainty after Brexit Day and to enable the government to repeal aspects of EU law afterwards. But, writes Joelle Grogan in the first of a two-part series on the Bill, the proposed Brexit Day division will still create a great deal of legal ambiguity. It is also questionable whether the UK can play a ‘leading’ role in human rights after removing the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The Great Repeal Bill is intended to convert all existing EU law into UK law. The aim is to provide legal certainty after Brexit Day and to enable the government to repeal aspects of EU law afterwards. But, writes Joelle Grogan in the first of a two-part series on the Bill, the proposed Brexit Day division will still create a great deal of legal ambiguity. It is also questionable whether the UK can play a ‘leading’ role in human rights after removing the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The outcome of the General Election will dictate the type of Brexit that the UK will aim to negotiate with the EU. It will also determine how the UK legal system will be reformed to reflect UK withdrawal. This will have consequences far beyond Brexit Day and the deal (or no deal) negotiated with the EU.

The Conservatives have outlined the process of legal separation and reform which will follow from ‘Brexit Day’ when the UK ceases to be a Member of the European Union in the Great Repeal Bill White Paper. Ostensibly aiming to balance the need for legal certainty with political expediency, the Great Repeal Bill proposes (1) to repeal only the European Communities Act 1972; (2) to convert EU law ‘as it stands at the moment of exit’; and (3) to create powers for Government to make secondary legislation which will ‘enable corrections to be made to the laws that would otherwise no longer operate’. [1.24]

The White Paper briefly outlines some considerations for the devolved legislatures and overseas territories, though does not address substantial issues arising from their distinct legal and constitutional structures, EU citizens’ rights, or borders with EU Member States (these last two issues are to dealt with by the Withdrawal Agreement with the EU).

In Part One of this post, I focus on the repeal and conversion of EU law, and show how the White Paper proposals create more issues for legal certainty than they resolve. In Part Two, I look at the delegated powers.

(1) Repeal

The ‘Great Repeat Bill’ is a misnomer, as it will not repeal all EU law in the UK. In fact, the only element of repeal in the Great Repeal Bill will be the repeal of the European Communities Act 1972 [ECA 1972]. The ECA 1972 is the UK act which gives effect and supremacy to EU law in the UK, and underlies a significant corpus of law in the UK by incorporating the acquis of EU membership, notably the EU Treaties and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, into UK law. Two immediate issues to highlight are the uncertainty with regard to the status of EU law in the UK, and the impact on fundamental rights protections in the UK as a result of the Great Repeal Bill proposals.

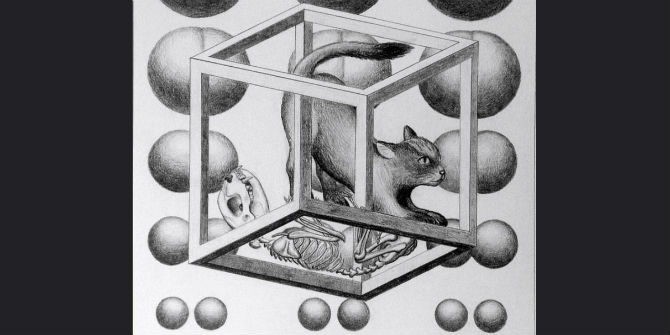

Schrodinger’s supremacy: The status of EU treaties and EU law post-Brexit

The doctrine of supremacy means that in the event of conflict between EU law and national law in a situation which is governed by EU law, the EU law must be applied and national law must be set aside (please note, this does not mean strike down – the national law will apply where EU law does not). The doctrine aims to guarantee uniformity in the application of law throughout the EU: Member States cannot pick and choose which EU laws to apply and which to ignore, and so a ‘level playing field’ in the single market is assured.

The White Paper states (in bold) that the ‘Great Repeal Bill will end the supremacy of EU law’ in the UK. [2.19] However, in the next sentence it acknowledges that, in the event of conflict, converted EU law will continue to take precedence over pre-Brexit national law – i.e. the supremacy of EU law remains. Similarly, while the content of the EU Treaties will be ‘irrelevant’ post-Brexit [2.9], provisions of the EU Treaties may still serve to assist in the interpretation of converted EU law by the UK courts. [2.10] EU Treaties and converted EU law will therefore exist in a strange state of both having and not having supremacy over pre-Brexit law. It would be left to the observation of the Courts as to when the precedence of converted law does (or does not) exist.

The UK’s ‘leading role in advancing human rights’: removing the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights codifies fundamental rights, including ‘first-generation’ rights of life, liberty and the prohibition on torture and the death penalty, as well as ‘third-generation’ rights such as the protection of personal data. The EU Charter can be relied upon in national proceedings when the subject-matter of the litigation falls within the scope of EU law. As the Charter has equal legal status to the Treaties, a violation of a right protected by the EU Charter requires the disapplication of the violating national law or practice. The repeal of the ECA 1972 aims to end the effect of the Charter of Fundamental Rights in the UK and to remove the oversight of the Court of Justice of the EU in the areas of law which fall within the scope EU law, including Charter rights.

The White Paper declares that the EU Charter should not be used to ‘bring challenges against the Government, or [to strike down] UK legislation’ [2.23], and so the Charter and the rights codified within it will not be converted into UK law. Strangely, the White Paper then asserts that this will not undermine ‘substantive rights’ which otherwise have existed and exist elsewhere in EU law, and thus will be converted into UK law. The White Paper references these as ‘underlying rights’ which will be relevant to the interpretation by the UK Courts, even when interpreting references to the Charter in converted case law. [2.25] The confusion of what constitutes an ‘underlying right’ when we have to ignore the codified account of them creates significant legal uncertainty, and undermines codified rights (ie data protection in the age of information) which do not exist at common law or in other rights instruments.

Even where the aim is to remove the rights and protections guaranteed by the EU Charter, the White Paper argues that Brexit will not change the UK’s ‘leading role in protecting and advancing human rights’ [2.21] as the Charter is only ‘one element in the UK’s human rights architecture’. [2.22] It identifies the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR] and mentions (without identification) UN and international treaties as part of this architecture. [2.22]

The distinction between the normative clout of the ECHR and the EU Charter is striking. The ECHR is operative in the UK through the Human Rights Act 1998. Under the 1998 Act, where a law violates an ECHR right to such a degree that it is not possible for the Courts to interpret the law in a way which does not violate that right, the most serious consequence is the issuing of a declaration of incompatibility. Such a declaration is a signal to Parliament that it should consider amending the legislation to take account of violated right. I am unaware of any UN or international rights instrument which has been incorporated into UK law, or can result in substantive remedies. Both the ECHR protections and international conventions starkly contrast with the protection afforded by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Where a law violates a right falling within the scope of the EU Charter, that law must be set aside.

The EU Charter will not be converted, uncertainty of ‘underlying rights’ introduced, and any substantive protections will be removed or weakened. What this leads to is the question of exactly what sort of ‘leading’ role in human rights is envisioned by the authors of the Great Repeal Bill.

(2) Conversion

It is not possible to repeal the ECA 1972 without undermining large areas of the law, and creating an unstable situation whereby the rules under which individuals and businesses are operating have no legal basis. The resolution proposed is the complete conversion of EU law into UK law on Brexit Day. This is aimed to guarantee a degree of legal certainty, and allow time for the reform of the law in the months and years (perhaps decades) which will follow.

The task of conversion is complicated by the diversity of EU law norms within the UK legal system: some primary acts are directly based on EU obligations (ie Equality Act 2010), while others are sourced in directly effective EU law, or in secondary legislation. Similarly, the acquis of EU law, including the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) has formed part of the way in which domestic law has been interpreted. EU law directly relates to areas of UK law as diverse as competition, agriculture, trade, energy, and telecommunications. To give examples from the last week of the wide scope of EU law, compensation to passengers for the cancelled British Airways flights, and the end of roaming charges are based on EU law. While there will be many issues critically raised by complete conversion, I highlight two broad issues here: the fossilisation of EU law, and the weakening of protection for workers, consumers and the environment.

Set in stone (and fossilised): case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union

Understanding that CJEU judgments form a significant part of UK law as regards the interpretation of EU law, the White Paper proposes that ‘historic’ CJEU case law will be given the same status as binding precedent in UK courts as decisions of the UK Supreme Court. The Great Repeal Bill will not provide any future role for the CJEU in the interpretation of converted law, nor require domestic courts to consider its jurisprudence. [2.13] In essence, this will mean that case law decided after Brexit Day will have no recognised status in the UK. Leaving to one side the kind of pressure that will now be placed on the Courts by practitioners to either expedite proceedings or delay them indefinitely, the Brexit Day division raises as many issues from the perspective of legal certainty as it designs to resolve.

Judgments of the CJEU are relevant where they aim to guarantee uniformity in the application of law throughout the EU: Member States cannot pick and choose which interpretation of a law they would prefer. Fossilising the case law on Brexit Day would leave UK law based on EU norms static and of limited use in cross border matters where the law in the EU-27 is subsequently changed or repealed by the EU legislator, or reformed and clarified in a subsequent case by the CJEU.

For expedience and practicality, it may be good practice for legal practitioners to continue to argue post-Brexit Day CJEU case law as persuasive precedent in cases involving concomitant converted law to minimise divergence. This would, however, only apply in cases where there is no prior judgment in a UK court or where the Parliament has legislated in the area. The Great Repeal Bill leaves no place for the CJEU post-Brexit, but this will be a key issue for the negotiation as the EU will aim to guarantee the uniformity of application of its law and guarantee the rights of its citizens.

Rights, right here, right now: workers’ rights, environmental and consumer protection

The White Paper recognises that a significant source of rights in the UK has been the EU Treaties, and recognises worker and consumer rights as well as environmental protection. [2.17] It underlines that in many areas, UK employment law sets higher than minimum standards, and reasserts a commitment to continuity of these rights – for example, stating that the Equality Act 2006 and Equality Act 2010 will continue to apply though they are based on EU obligations. [2.17] From the perspective of environmental protection and consumer rights, the White Paper emphasises continuity of the established frameworks and rules.

The important element is to highlight that a guarantee of continuity of existing rules is not the same as entrenching these rights. Currently, membership of the EU demands certain minimum standards of protection in these areas, and this requirement will end on Brexit Day. The right to complain to the Commission for a violation of these standards, or for the Commission to bring proceedings in the Court of Justice for a violation of environmental, consumer or workers’ rights will end. Consumer, worker and environmental rights will become (as they have already) a political, rather than legal, issue. They would continue post-Brexit, unless it became politically expedient for them (for example, for trade deals) not to.

Only uncertainty is certain

The White Paper for the Great Repeal Bill sets out the Conservatives’ proposals for the process of separation, reform and revision which will follow Brexit. The repeal of the ECA 1972 and the conversion of EU norms into UK law on Brexit Day aimed to deliver both the legal separation of UK law from the EU but also a degree of legal certainty. In effect, it compromises both and achieves neither. This is not even, however, the most concerning part of the Great Repeal Bill White Paper. In Part Two I consider how Government intends to quickly ‘correct’ EU-derived primary and secondary law through delegating power to Government to change the law with little scrutiny or constraint – a Henry VIII power of unprecedented scale and scope.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Joelle Grogan is a Lecturer in Law at Middlesex University.

The (not so) Great Repeal Bill, part 2: How Henry VIII clauses undermine Parliament