Theresa May was adamant that the UK would not accept the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice after Brexit. But as reality has sunk in, that red line has begun to blur. LSE Fellow Anna Tsiftsoglou explains why the ECJ is such a vital issue in the exit negotiations. To reverse David Davis’ footballing metaphor, if the UK plays in EU territory, it has to accept EU rules and referees.

Theresa May was adamant that the UK would not accept the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice after Brexit. But as reality has sunk in, that red line has begun to blur. LSE Fellow Anna Tsiftsoglou explains why the ECJ is such a vital issue in the exit negotiations. To reverse David Davis’ footballing metaphor, if the UK plays in EU territory, it has to accept EU rules and referees.

At the 2016 Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May emphatically declared to her party that ‘’we are not leaving (the EU) only to return to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. That is not going to happen.” Fast forward nine months: in July 2017, Mrs. May, deeply wounded at the recent snap election, and already three months after triggering the famous Article 50 of the Treaty on the EU – aka the Brexit procedure – has eventually conceded a transitory role for the highest court of the EU.

What does that mean, and what could explain this policy shift by the British government?

The European Court of Justice (‘the ECJ’) is the highest court of the EU, with jurisdiction over the whole spectrum of EU legislation, primary and secondary. It is tasked to ensure the uniform application and interpretation of EU law. Ever since its establishment in the 1950s, the ECJ is considered the ultimate arbiter of all matters related to the EU Single Market.

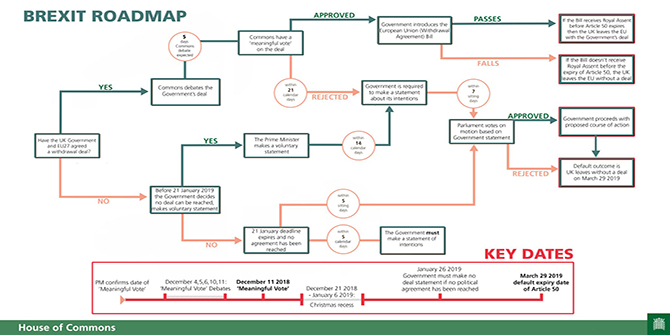

In the course of the Brexit negotiations – set to last at least until March 2019 – and thereafter, a significant load of EU case law on matters ranging from EU citizens’ rights in the UK to trade and immigration controls will probably arise or is currently pending at the Luxembourg court. Denying the ECJ’s jurisdiction on the disputes altogether and having them settled by British courts applying national law transposing EU law has complicated negotiations even further.

The UK government, while insisting on its hard Brexit lines, has gradually tried to soften them. In the recently published 66-page Repeal Bill, Brexit Secretary David Davis has revealed the Government’s statutory plan for the post-Brexit era. Essentially, the draft Bill repeals the 1972 European Communities Act with which Britain entered the EC and which established the supremacy of EU law over national law. To avoid any legal black holes, on exit day all the body of existing EU law and ECJ case law –a 40-year acquis– will be converted into domestic law, which UK legislators will be free to amend as they see fit. The British government might even use Henry the VIII powers to amend it without any parliamentary approval. As expected, the Repeal Bill has already and will probably again provoke a ‘hell’ when debated in parliament next autumn.

Much as the Repeal Bill ends the ECJ’s jurisdiction in the post-Brexit era, a fresh position paper shows the government’s willingness to negotiate the future of pending ECJ cases so as to provide ‘certainty’ to citizens and investors alike and ensure a smooth transition. Nevertheless, not all cabinet members have backed this position, a sign of the deep ideological chasms that exist both within UK-EU relations and the government itself.

Theresa May had misguidedly assumed that ‘taking back control’ of the country would mean denying any role for the EU’s highest tribunal in the new era. Such a red line would harm rather than benefit the country, while it remains a sticking point on the ongoing negotiations. Rather naively, this red line blatantly assumed that, in the course of Brexit negotiations, it would be the UK, not the EU, setting not only the rules but even being the referees of the game. In Brexit law and in reality, it is actually the other way around. It is the UK that is leaving, not the European Union dissolving its legal establishment or its institutions.

Ironically enough, the ECJ issue is yet another piece of the ongoing Brexit drama that started out a year ago in the aftermath of the 2016 referendum. Theresa May had initially believed she could go on with her hard Brexit plan defying any rules, including constitutional ones. However, as the majority of the UK Supreme Court confirmed in its seminal 2017 Miller case, the British government could not leave the EU without Parliament’s consent. Constitutional change for Britain, such as that brought about when the country entered the European Community in the 1970s, could only happen by law, and not by ministers alone. Unsurprisingly, the Miller case has restated the obvious – the respect of the constitution, and the rule of law.

As the UK enters more rounds of negotiations with the EU, Mrs May’s numerous red lines have started to blur. From freedom of movement concessions to transitional plans for pending ECJ case-law, the UK government is now heading towards not a hard but a pragmatic Brexit. Achieving a pragmatic Brexit would involve, inter alia, acknowledging a transitional role of the EU’s ultimate arbiter in the post-Brexit era – that is, coming to terms with what is feasible. Or simply following the Brexit rules of dis-engagement. To reverse David Davis’ football argument, if the UK plays in an EU territory, one way or another, then it should accept the same rules and referees for its disputes as the rest of the 28 teams of the EU league.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Anna Tsiftsoglou is the National Bank of Greece Fellow at the LSE Hellenic Observatory. Her research interests include constitutional law, human rights law and EU law and politics. She is currently working on a monograph on constitutional change in crisis-hit states from a comparative perspective, in the cases of Greece and Cyprus.

Thanks a lot for the very informative article. It seems that is getting really complicated for May’s government to get rid of the E.U.. I was wondering, whether that view has to do with some powerful bond the country still has with her glorious past (a kind of imagined structure perhaps as it has no straight connection with today) or it is just a British absence of realism and / or imagination in the way they handle their foreign affairs.

Except that, I was thinking whether we can talk about May’s wrong political estimations or for the adoption of a naive populism?

The Remain debate is centred on the supposed difficulty of extracting the UK from the ECJ.

A better question is to ask why a sovereign polity should prefer to have a supra national and political Supreme Court in which it has de minimis influence.

The ECJ is a political creature of the EU and exists to further the integrationist agenda of a “3rd country” – the EU.

Would it also be possible that even post the transition period/ in the final Brexit state of things, Britain would possibly still have to concede supremacy to the ECJ? If ,for example, it were to have access to the single market or make use generally of other EU wide constructs?